Long text: a feasibility framework for exploring cryptocurrency privacy and regulation

The cryptocurrency provides an alternative to the traditional method of electronic value exchange, which promises an anonymous, cash-like electronic transfer, but in practice, there are insufficient cryptocurrencies for several key reasons.

We believe that there is a wrong choice between comprehensive supervision represented by banks and supervision currently implemented by institutions. At the same time, this regulation has an insurmountable gap with the strengthening of privacy represented by cryptocurrency.

To this end, we identified a series of alternatives between these two extremes and considered two potential compromises that provide both the auditability required by the regulator and the anonymity that users need.

1 Introduction

- Big rise and fall! Bitcoin fell $1,100 after breaking $9,000

- Bitcoin skyrocketed, but the blockchain looked "indifferent"

- 800+ verifier node! What does the release of the Ethereum 2.0 test network mean?

The surveillance economy has arrived. The popularity of online service platforms has enabled service providers to collect, aggregate, and analyze data about individual behavior in an unprecedented amount and range. Data brokers create a marketplace for exchanging personal information that can be used to link their various online behaviors, including but not limited to financial transactions. This information, including the use of credentials in continuous transactions, can be used to link transactions to the counterparty. Such links can greatly simplify subsequent transactions, reduce provider costs and improve the customer experience.

However, the potential for monitoring profoundly affects the individual's daily behavior when performing various activities. The value of such control is reflected in emerging markets that establish record links through physical resolutions, which are designed to determine the specific individuals associated with any particular activity, as well as the activity history associated with any particular individual.

For a long time, people have always believed that privacy is a public product. It is worth considering whether this practice will limit the ability of those who have sufficient wealth and power to trade privately, thus exacerbating social injustice. Financial transactions are no exception, as they not only reveal the number and recipients of individual purchases and remittances, but also reveal their patterns, geographic history, social networks and more. The modern retail banking industry has created a “universal switch” for consumer behavior, and it is hoped that a mechanism will be implemented to bind all financial activities undertaken by individuals to a single identity. Consumers have a legitimate reason to resist such monitoring, especially if they are unaware of them, and judgments based on such monitoring are used to suppress or punish legitimate activities. The risks faced by consumers increase as the share of electronic transactions in financial transactions increases. The growing ability of third parties to collect and analyze retail financial transaction data has fundamentally changed the relationship between individuals and their financial institutions.

Cryptographic currency seems to be a natural choice for exchange value , avoiding the surveillance of countries, powerful companies, hackers and others who may be in a good position. However, the lack of proper regulation often imposes practical limitations and risks on cryptocurrency users. These risks include the lack of financial products and services, the inability to earn interest, basic consumer protection, and the lack of legal infrastructure for arbitration disputes. China also restricts the use of cryptocurrency exchange as a means of addressing capital outflows.

In addition, most cryptocurrencies do not enhance privacy as generally thought, and as governments try to establish a cordon around criminal activity that relies on cryptocurrencies, some governments are already actively looking for ways to undermine the use of cryptocurrencies.

For example, the Financial Services Agency pressured cryptocurrency exchanges to abandon privacy-enhancing tokens, such as Monero Adelstein.

One of Korea's largest cryptocurrency exchanges will enhance the delisting of privacy tokens.

The US Department of Homeland Security specifically called for ways to circumvent cryptocurrency privacy protection. To be exact, it is to avoid the privacy protection of privacy tokens.

In addition, whether these government initiatives succeed in preventing untrackable cryptocurrencies from being mainstreamed, even the most private cryptocurrencies face tough governance challenges associated with building a decentralized network that respects the user's interests.

As a result, we are in a stalemate. On the one hand, institutions demand control and support for monitoring. On the other hand, online liberals demand privacy at the expense of regulation.

Let's start this article

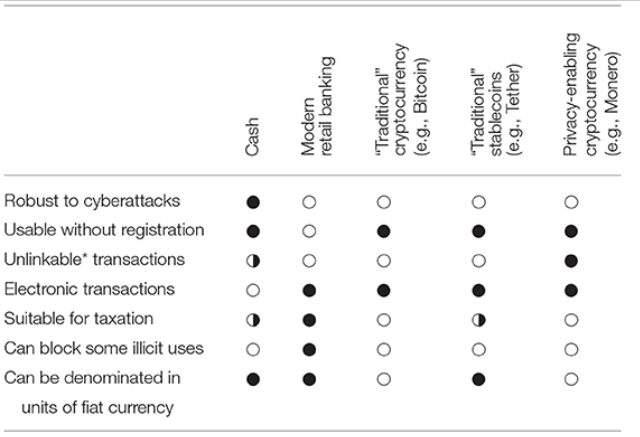

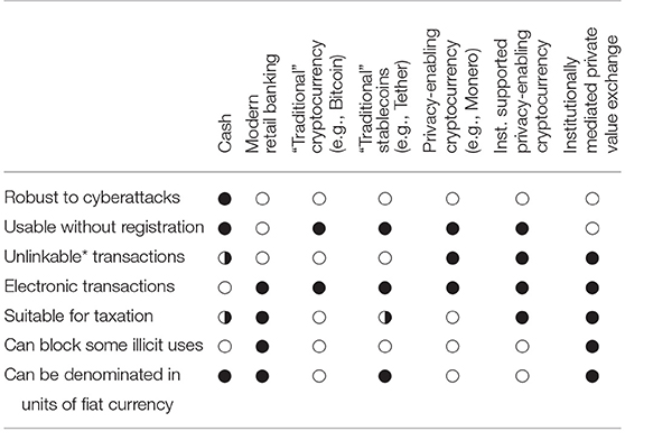

The attributes that the payment system should have. They are listed in Table 1. In addition to usefulness, security and privacy, we have also noted various arguments about money as “an effective payment for all debt” and for funding government activities through taxation.

We discuss how to redefine our needs so that we can achieve regulatory goals while respecting privacy and meeting our needs.

Table 1: Required electronic payment methods.

The paper is organized as follows:

In the remainder of the first part, we will discuss the regulatory environment surrounding modern retail financial transactions and introduce cryptocurrencies as potential replacements for regulated payments.

In the second part, we compare and contrast the three online financial transactions: modern, regulated retail banks; classic cryptocurrencies such as Bitcoin; and cryptocurrencies that support privacy, such as Monero.

In the third part, we will introduce two candidate methods, each of which provides individuals with a verifiable way to conduct private transactions and provides appropriate mechanisms through which organizations can enforce compliance. In the last section, we will discuss opportunities and trade-offs.

1.1 Institutional posture

In recent years, banks have invested heavily in building and maintaining a compliance infrastructure, employing thousands of employees to monitor “high-risk” transactions, and “tens of thousands of expensive customer calls per month to refresh KYC files”.

In 1989, the Group of Seven established the Financial Action Task Force (FATF), an international organization that monitors financial activities to investigate and prevent money laundering and terrorist financing. The FATF provides one of the mechanisms for enacting and coordinating “anti-money laundering”/KYC regulations in different jurisdictions. The FATF also issued a blacklist of countries that failed to implement rules that help identify and investigate individual account holders in order to coordinate sanctions and force blacklisted countries to comply with these sanctions.

Financial regulation implemented by economic powers such as the United States and the European Union has common characteristics. In the United States, “anti-money laundering” regulations regulate customer identification and monitoring, as well as reporting requirements for suspicious activity. Each financial transaction must be associated with an account, and each account must be associated with a clear, responsible individual. The directive also significantly reduces the maximum allowable value of prepaid cards and stipulates that remote transactions exceeding €50 must be accompanied by a customer identification. Note that 5AMLD specifically includes cryptocurrency to comply with its regulations regarding financial transfers.

While systematically collecting personal account holder identification information may be useful for conducting important investigations, it also provides a mechanism by which the authorities can unknowingly browse the full or near-comprehensive financial information of the individual concerned. Authorities with these capabilities, as well as companies that are able to collect and analyze data collected for compliance, may also be able to perform statistical evaluations of individuals based on information held by their financial institutions. Once the transaction data collected by financial institutions is aggregated and associated with a unified identity, you can view individual habits, patterns, travel, connections, and financial health.

1.2 cryptocurrency

In recent years, cryptocurrencies have become more and more popular, and people flock to cryptocurrencies for a variety of reasons. The concept of no account digital cash is not new, at least as far back as David Chaum's 1982 paper on blind signatures, which he later used to create DigiCash Inc. Other attempts to develop account-free electronic payment systems, such as E-Gold and the Free Reserve Bank, were designed with privacy in mind, and when criminals used these systems for illegal purposes, they eventually collided with the authorities.

By the time Bitcoin appeared in early 2009, the financial crisis had triggered positive reactions from central banks around the world, and it was no coincidence that information to circumvent inflation monetary policy was welcomed among potential hoarders.

However, given that privacy is a major motivation for adopting digital currencies, we speculate that many cryptocurrency adopters (except speculators) are primarily seeking privacy, whether to circumvent capital controls or simply to avoid “idyling gaze” monitoring by the state or business. .

Some important developments in recent years have confirmed this view, most notably trying to develop a “stable currency”: a cryptocurrency that avoids volatility in cryptocurrency by establishing market linkages. The most notorious example of "stable currency" is Tether, a cryptocurrency that was created to maintain a one-to-one link to the dollar. Therefore, stable currency can be denominated in legal tender. However, stable currencies have important restrictions, including general and reasonable concerns about unilateral exchange rate pegs.

As an alternative to the “legitimate” currency that is fully trusted and credit-backed by sovereign governments, cryptocurrencies are far from perfect. This has structural reasons, including:

1. Lack of financial services. It is worth noting that there is a lack of reliable organizations to provide daily financial services, such as loans, and more importantly, lack of regulatory support for cryptocurrencies. In addition, the cryptocurrency sector is often unable to correct or revoke erroneous transactions using unlicensed cryptocurrencies compared to transactions conducted through global messaging systems such as SWIFT, which is a critical operational limitation. In order for cryptocurrencies to truly replace government-issued currencies, they must support a range of markets and financial products.

2. Lack of regulated markets. History tells us that unregulated markets for financial products may be harmful to ordinary citizens and businesses. For example, the misconduct of economic companies and market participants led to the establishment of the US Securities and Exchange Commission. The cryptocurrency market lacks such controls and mechanisms to ensure accountability, and unconstrained market manipulation is common.

3. Lack of legal background. There is no universally applicable ruling mechanism for disputes arising from transactions executed using cryptocurrency. When auto-executing contracts, such as those that support "distributed autonomous organizations." For example, when the Ethereum community was used in 2016, the unfortunate victims had almost no legal recourse. Although “certain operating terms in legal contracts” may automatically produce beneficial effects, the concept of maximizing the “code as law” principle does not seem to be feasible without a proper legal framework.

In addition, cryptocurrencies often fail to deliver on their key commitments. For example, they are often not as private as people usually think. Analysis of bitcoin transactions can be anonymized, and researchers have shown that it is very possible to identify meaningful patterns in transactions. This problem persists not only because of the reuse of the network tracker and pseudonyms associated with bitcoin wallets, but also because inbound transactions for bitcoin addresses can be fundamentally associated with outbound transactions for that address.

In fact, some even believe that the explicit traceability of transactions on Bitcoin books, coupled with the direct method of tagging suspicious transactions, makes Bitcoin less private than traditional payment mechanisms. Even cryptocurrencies designed for privacy like Monero have proven to be important weaknesses.

Another equally important flaw is that cryptocurrencies are not as fragmented as people usually think. While decentralization is often touted as a reason for the existence of cryptocurrencies, in practice, “mining” and infrastructure services associated with cryptocurrencies remain stubbornly concentrated for a variety of reasons. The issue of decentralization is closely related to more fundamental governance issues, namely how to ensure that the system serves the interests of its users. Without institutional support, there is nothing to ensure that the situation remains the same.

Governance issues have special significance for stabilizing currency companies. Importantly, if a stable asset is not maintained and controlled by the central bank, then its users will need to care who can ultimately guarantee that it will retain its value.

2. Current electronic payment

In recent decades, with the rapid development of electronic funds transfer systems, people are increasingly expecting to use these systems. If this trend continues, we expect that the fixed costs associated with the infrastructure that supports cash transactions will become more difficult to justify, and variable costs such as the widespread deployment of ATMs will be reduced. Individuals and small businesses have multiple options for electronic transactions. “Electronic” financial transactions include almost all economic transactions that do not use cash, despite the use of precious metals, money orders and barter transactions. For our purposes, all payments involving institutional accounts, including bank card payments (via payment networks), wire transfers, ACH, and even physical checks, are made electronically, as are payments made using cryptocurrencies.

Next, we will consider the characteristics of the transaction in three electronic payment examples: transactions involving institutional accounts, transactions involving "basic" cryptocurrencies, and transactions involving "private privacy" cryptocurrencies.

2.1 Modern retail banking

Modern retail banking involves electronic transactions between accounts, each representing a bilateral relationship between a financial institution (such as a bank) and another entity (possibly an individual). Institutions are usually managed by the government. Individuals and businesses may agree to exchange value (for example, in exchange for goods and services), but the reality is that transactions occur between agencies, they mutually agree to modify the status of the account, so that the "recipient" account is increased, and "the sender The account is correspondingly reduced.

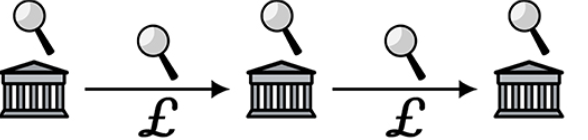

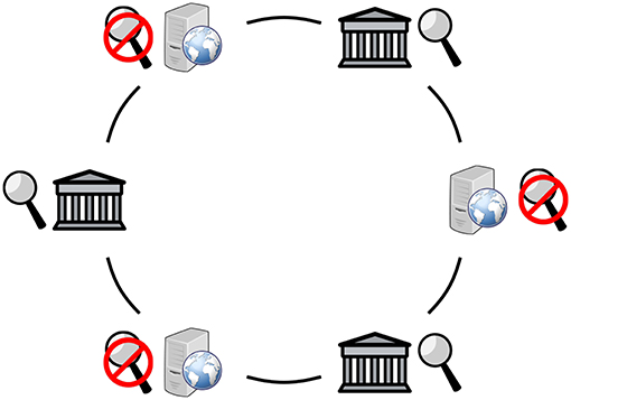

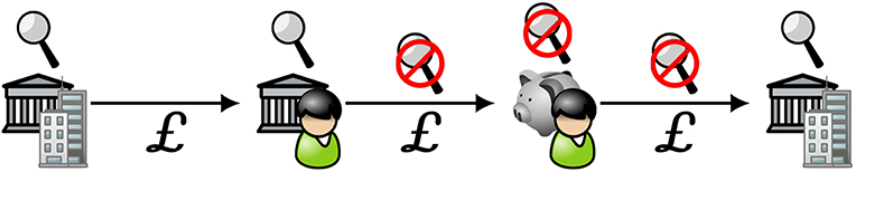

Records of transactions and their results are usually visible to agencies, accountants, authorities and auditors. Figure 1 shows the data flow corresponding to two transactions. The institution is a direct participant in the transaction. Accounts and transactions can be monitored, that is, “external” observers, such as authorities (and in some cases, other observers, such as unprivileged employees and hackers of the organization) can check transaction records, results, and the transaction itself. Because of the small number of regulated institutions, it is effective for observers to collect, aggregate, and analyze data related to almost all transactions that occur within the system.

figure 1

Figure 1 shows. Schematic diagram of the modern retail banking transaction process. A building with pillars represents a financial institution that holds the accounts of both parties to the transaction. Currency is exchanged in the currency of the country, expressed in pounds sterling. As the magnifying glass shows, authorities and other powerful actors can simultaneously monitor these institutions and financial flows.

In contrast, observing transaction data involving cash in this way is relatively difficult, so cash transactions are more private. However, while cash is still a popular retail trading tool, the use of cash is decreasing as consumers' acceptance of electronic payment methods increases. Some economists such as Kenneth Rogoff praised the shift as a welcome trend, and they believe that reducing tax evasion and crime is the main benefit of reducing anonymous payments. Others are more cautious. Jonas Hedman, for example, in Sweden's cashless, acknowledges that the loss of privacy is a major disadvantage of a cashless society, although he acknowledges that the transition to cashless is inevitable.

2.2 "Basic" cryptocurrency, such as bitcoin

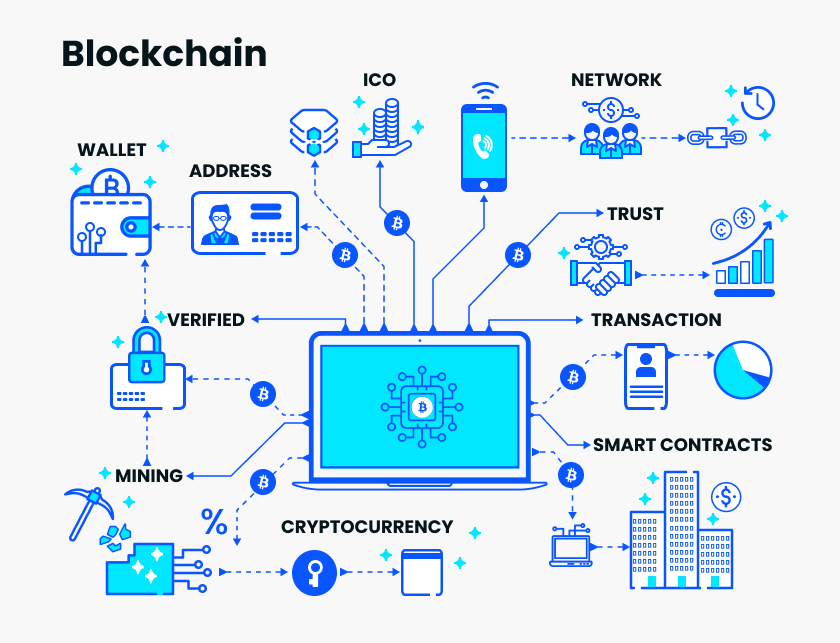

Cryptographic currency provides an alternative payment mechanism that avoids some aspects of surveillance, while regulatory infrastructure is a hallmark of institutional-mediated retail banking transactions. Modern cryptocurrencies are usually in the form of bearer notes because their units are represented by public keys on the public ledger and are controlled by matching private keys. Users do not need to create an account or provide any type of identity information to receive, own or use cryptocurrency.

This is not to say that the account does not exist. Most users of popular cryptocurrencies such as Bitcoin and Ethereum have established accounts with centralized wallet providers such as blockchain.info or myetherwallet. Account providers may be harmed or subverted by national actors or other powerful groups interested in monitoring. Some account platforms work with national regulators, and some national regulators have announced restrictions on the scope of the rules applicable to such platforms. Therefore, even if most traders may be indifferent to the strict identity requirements of regulators to meet the “anti-money laundering” goals in practice, these regulations will undermine a key design goal of the cryptocurrency itself.

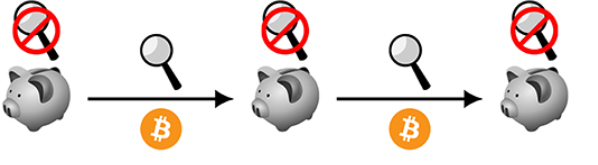

However, in principle, users of cryptocurrencies do not need to register on the platform, they can have cryptocurrency tokens on their devices. Figure 2 shows how this works in practice. It is assumed that cryptocurrency users take precautions when conducting transactions, such as anonymous systems such as Dingledine, who may wish to avoid identity-based blacklists when receiving tokens. However, depending on the system design, the opponent may still be able to monitor. Because consecutive bitcoin transactions are linked to each other, those who are able to monitor the network can determine the continuous transactions associated with a particular token, ultimately eliminating the anonymization of Bitcoin users.

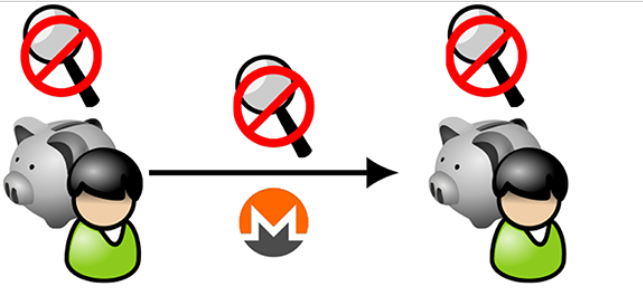

figure 2

Figure 2 is a schematic diagram of the bitcoin transaction flow. Transaction parties can store value on their devices, such as piggy banks. In the process of circulation, anyone can monitor.

Therefore, an individual may be less willing to accept certain cryptocurrency tokens because doing so may implicitly link the individual to the former owner of the token. Traceability creates a need for newly generated or "clean" tokens that are more difficult to link to previous transactions by the previous owner or current owner.

The proposed blacklist of cryptographic currency addresses associated with suspicious operators may further exacerbate this difference. To avoid this problem, the cryptocurrency needs to ensure that the asset holder's transaction typically does not directly or indirectly cause the asset holder to be associated with other transactions that have occurred before. In addition, cryptocurrencies that use immutable ledgers and do not guard against traceability may therefore not comply with data protection regulations, such as the GDPR that stipulates the “right to be forgotten”.

2.3 "Privacy enabled" cryptocurrency, such as Monero

Some cryptocurrencies, especially Zcash and Monero, are explicitly designed to address traceability issues. In particular, Monero uses a method that includes the following security mechanisms:

1. A ring signature that allows a signed message to be attributed to "a set of possible signers without revealing which member actually generated the signature."

2. Invisible address refers to the method used for key management, in which the public key is derived from the private key and used to obfuscate the public key.

3. Encrypted transactions using the Pedersen Commitment Plan to limit the disclosure of the transaction amount to anyone other than the parties to the transaction.

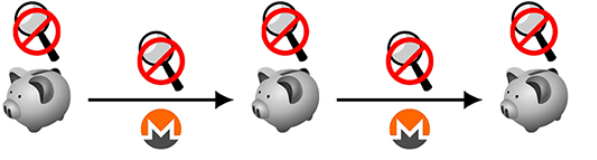

Figure 3 illustrates how transaction-related metadata is hidden in a successful implementation of privacy-enabled cryptocurrencies so that the data stream or ledger does not display relationships between transactions or any information about parties to the transaction. In other words, Monero's design and implementation has not fully achieved this goal. The process of its mixed transaction has the problem that the selection probabilities between all elements of the anonymous set are inconsistent. Monero spokesperson Riccardo Spagni retorted that “privacy is not what you achieve, it is a constant cat-and-mouse war”, echoing the long-standing view of others that privacy is inevitably a vigilance and response. Work hard.

image 3

Schematic representation of the Monero transaction flow. In the "idealized" version of Monero or other privacy-enabled cryptocurrencies, observers cannot infer information about the relationship between parties or transactions by monitoring the ledger or the transaction itself (a magnifying glass with negative signs). The piggy bank indicates that the user is storing the token privately, rather than relying on the account.

Some authorities, such as the Japan Financial Security Administration (FSA) and the US Secret Service, responded to so-called “privacy coins” by prohibiting the use of cryptocurrencies that enhance privacy and accepting other cryptocurrencies as more legitimate currencies. To comply with these rules, cryptocurrency exchanges or other cryptocurrency-based financial services need to limit their activities to cryptocurrencies such as Bitcoin and Ethereum, which do not have cryptocurrency advocates. The privacy features that have been sought for years.

Of course, there are some attempts, especially the Mimblewimble protocol, which is used to transform the basic cryptocurrency. Although the inherent privacy of this method design remains to be seen, it has some features of cryptocurrency that support privacy.

3, proposed a hybrid approach

We believe that policy makers, regulators, and technicians all face the challenge of how can we achieve the real benefits of government regulation without creating a central database that connects all people irreversibly with all of their transactions?

There are two parts to this problem. The first part is about technology: Can we build a system to handle e-finance transactions securely without revealing the data of the parties to the transaction.

The answer is yes. As we discussed in the discussion of privacy-enabled cryptocurrencies, there is an important stipulation that privacy is actually an iterative process that can only be truly developed through active commitment and ongoing vigilance.

The second part is mainly about government policy:

• What are the key objectives of government regulated transactions?

• What goals are necessary and which ones can be deprived?

• Do these goals conflict with privacy?

Table 2 shows how existing payment methods implement the wishes listed in Section 1. (Despite continuous improvement, no popular cryptocurrency can provide completely unlinkable transactions). Can we reach a compromise that makes electronic payments better than what is currently popular?

Table 2

Table 2 compares the various existing electronic payment methods.

In this section, we'll look at two ways to build a discussion framework for how to resolve this tension.

The first approach is to institutionally support private cryptocurrencies, provide regulated institutions with tools and procedures to interact with cryptocurrencies that support privacy, and create a structure for legal interpretation of cryptocurrencies.

We assume that the distributed ledger behind these cryptocurrencies is not controlled by regulated financial institutions.

The second method is institutional-mediated private value exchange. It establishes a method by which regulated institutions can conduct financial transactions on distributed ledgers, while distributed ledgers have the same basic characteristics as cryptocurrencies that support privacy.

In this case, we assume that the distributed ledger used for this purpose is controlled by a regulated financial institution. The main difference between the two approaches is that the first approach allows companies that manage and manage cryptocurrencies outside the mainstream financial system. The second approach provides a way for regulated financial institutions to offer their customers a currency exchange mechanism similar to cryptocurrencies, because customers can withdraw money electronically and then use it without reference to the account, just like they Use cash as well.

There is also a third possibility, which we can describe as "an institutionally supported stable currency that protects privacy." In this mechanism, the cryptocurrency supported by privacy is actually stable. If the stability of a stable currency is comparable to that of a cryptocurrency, then in theory, this possibility is worth pursuing, although Tether's experience suggests that this may not be easy.

It is worth considering that the proposal to mediate the private value exchange in the system is similar to a stabilization mechanism, that is, the unit in which the token represents legal tender. However, since regulated financial institutions are assumed to be part of the banking system, they will not be exposed to the risks associated with maintaining market linkages.

3.1 Institutional support for cryptocurrencies that support privacy

Our first method is to start with an existing, cryptocurrency that supports privacy, such as Zcash or Monero. It is also assumed that the regulator chooses to accept the new method of exchange value, has chosen to adopt a new value exchange method, and accepts, if not fully supported, at least some governance and software development for communities formed around a particular cryptocurrency.

It is certainly reasonable for the government and other institutions to accept cryptocurrencies. For example, the Bank of England believes that cryptocurrencies “are not currently posing a substantial risk to UK financial stability”. It assumes that the government's top priorities include taxation and supervision of transactions between companies and regulated institutions.

Figure 4 illustrates how an organization joins an existing cryptocurrency system as a full participant. Motivations for the participation of economic self-employed and other institutions have been established, and hedge funds and other customers have strong demand for cryptocurrency-related financial services. Of course, this means that economic self-employed companies may engage in activities related to unregulated markets and markets. (such as the cryptocurrency itself), and the governance of cryptocurrency is probably not controlled by the organization. That is, the distributed ledger behind the cryptocurrency will ensure an audit trail for all transactions, even though the details of these transactions may be mysterious to authorities, auditors, or others who are not actively involved in the transaction.

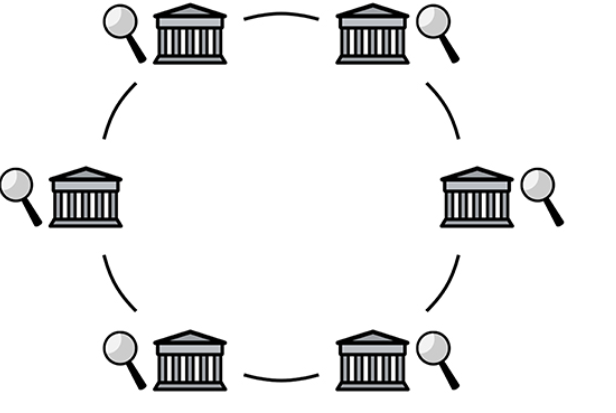

Figure 4

Figure 4 is a schematic diagram of an organization-supported privacy-enabled cryptocurrency: nodes, organizations will join a global network of servers running as existing cryptocurrency network nodes, and not all of these network participants are regulated.

In order to facilitate monitoring, auditing, and taxation. We assume that regulators will stipulate that all cryptocurrency transactions by legal entities other than certain individuals, such as registered companies, registered companies, charities, trusts, and some partners, must pass through regulatory agencies such as banks, custodians or the economy. Self-employed.

In general, these legal entities have been subject to various forms of government regulation, such as tax filing requirements, so the introduction of additional requirements and enforceability for cryptocurrency transactions is not difficult to accomplish. These institutions will implement the “anti-money laundering”/KYC compliance program as they do today, and the regulator will require all cryptocurrency payments to be processed and paid from registered companies or organizations, including dividends, interest, and acquired cryptographic assets, including but not limited to payments to supplies. Merchants, service providers, employees and contractors will take the form of remittances to other institutional accounts holding cryptocurrencies.

Individual and non-commercial partnerships will not be bound by the same requirements and will be allowed to trade privately and hold cryptocurrencies, as they do today in many countries. Figure 5 shows how this works in practice. The company will open an account in the institution and may instruct the institution to remit funds to accounts held by other institutions, including those who benefit the owner as individuals, and individuals can directly transfer funds from their institutional accounts to their private individuals. In a cryptocurrency store, these cryptocurrency stores may or may not be hosted by a wallet provider.

Individuals can then send money from their private storage to regulated companies (such as merchants, private organizations, or service providers) without having to reveal their identity or deal with previous transactions (such as which transactions they originally originated from) Get a link to the cryptocurrency). Figure 6 provides an illustration. In view of the fact that the legal entities mentioned in the last paragraph are usually subject to financial reporting requirements, such as quantitative compensation or reconciliation of changes in asset income, we believe that it is no easier for a company to entrust an individual representative to conduct cryptocurrency transactions. The business entrusts the individual to conduct any other financially more meaningful business.

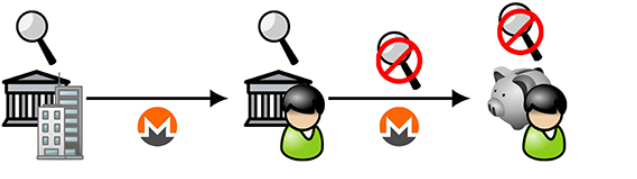

Figure 5

Figure 5 is a schematic representation of an organization-supported privacy-enabled cryptocurrency: transaction flow (1). (We use the Monero symbol to represent any cryptocurrency that supports privacy without losing versatility). Companies and registered companies that hold accounts by regulated financial institutions (the leftmost icon) will be regulated and will only be able to transfer cryptocurrency payments to other accounts held by regulated financial institutions. Personal and non-commercial partnerships (center icons) can transfer cryptocurrency from an account to an unmonitored private store (the rightmost icon).

Image 6

Figure 6 is a schematic diagram of the cryptocurrency supported by the organization and guaranteed privacy: transaction flow (2). Individuals with private storage in cryptocurrencies (see image on the left) can send money to companies with regulated accounts (see image to the right) without revealing their identity.

Depending on whether the cryptocurrency is held by an account associated with the regulated institution, we divide the different holding methods of the cryptocurrency into two categories, which is similar to dividing Zcash into "T" (transparent) and "Z" (masked) addresses. .

Since all cryptocurrency accounts held by companies and registered companies will be monitored by regulated agencies, the infrastructure will ensure that the taxable income of these companies and businesses is known. Since all payments from companies and registered companies must be remitted to other institutional accounts, the infrastructure will ensure that the revenues of its shareholders, suppliers, service providers and employees will be known and attributed to the correct legal entity. The authorities will also receive other benefits. The distributed ledger maintained by the cryptocurrency node operator will be seen by regulators and other agencies and cross-referenced to any cash flow statement of the firm engaged in cryptocurrency transactions. Private transactions involving suspected criminal activities can be verified by investigators in cooperation with a counterparty, even though the investigation may not necessarily reveal the other's identity.

Figure 7 shows a type of transaction that may be of particular interest to the authorities under this system, where an individual with a private cryptocurrency store transmits cryptocurrency to another person with a private cryptocurrency store, without involving a regulated institution.

In fact, such transactions can be conducted without institutional involvement, which means that the authorities will not be able to completely limit who can trade based on the FATF's recommendations. We can think that regardless of whether the FATF recommends sanctions, the value will flow to criminal organizations. Or those who are willing to break the law have many choices to anonymously obtain "legitimate" accounts, or potential money launderers with sufficient assets will find other ways to trade outside the system. Whether or not this view is justified, cryptocurrencies may become the dominant form of exchange value, precisely because people value privacy, in which case regulators will need to support cryptocurrency transactions simply because these transactions are taking place. After all, people must have exchanged value before the central bank began issuing money.

Figure 7

Figure 7 is a schematic diagram of an organization-supported privacy-enabled cryptocurrency: transaction flow (3). Individuals with private storage of privacy-backed cryptocurrencies can trade directly without revealing their identity.

Equally important, the characteristic of this approach is that if there is no institutional adjustment as the core, the cryptocurrency will be subject to mining pools, hackers, powerful global players that may endanger or hijack cryptocurrencies, and may be exhausted. The influence of speculators and market operators who encrypt the value of money. However, another explanation for this attribute is that different cryptocurrencies will compete with each other, not only based on market penetration, but also on privacy. It is hard to imagine a monopolistic currency, whether government-supported or otherwise, has this characteristic.

3.2 Institutional Intermediation Private Value Exchange

Our second approach first assumes that "public" cryptocurrencies are not suitable for all types of institutional support , as may be mentioned in Section 3.1. Instead, it suggests establishing a distributed ledger for conducting financial transactions, and each node of the distributed ledger will be owned and operated by a regulated agency. As shown in Figure 8, this can be achieved through a "licensed" distributed ledger system, such as the Hyperledger, which uses an efficient Byzantine fault-tolerant consistency algorithm such as PBFT. Users and governments will benefit from the fact that the counterparty does not need to use a cryptocurrency of questionable value, but can actually trade it using a digital version of the currency issued by the state, ie, currently, central banks around the world are considering adopting digital currency, which Currency can bring a variety of economic and operational benefits.

Figure 8

Figure 8 is a schematic diagram of agency-mediated private value exchange: nodes, distributed ledgers are managed by a consortium of regulated agencies.

At this point, people may be reluctant to suggest that since the entire network consists of regulated or approved financial institutions, the government should require a “primary key” or other special access mechanism to break the user’s anonymity. .

We advocate that this temptation should be resisted. For many years, policymakers have been calling for widespread application of anomalous access mechanisms in a variety of situations. After extensive debate, it was found that such appeals were premature and subsequently withdrawn. In fact, legislators in the United States and France have gathered to oppose special access mechanisms on the grounds of their inherent security weaknesses and the possibility of abuse.

In fact, to make our approach a private value exchange, regulated institutions must work to promote private transactions. To some extent, these organizations must employ specific technologies, such as ring signatures, encrypted addresses, and encrypted transactions, which are used by privacy-protected cryptocurrencies such as Monero. On another level, these institutions must commit to ongoing efforts to audit, challenge, and improve technology and operational procedures, as privacy-enhancing technologies need to be vigilant.

Therefore, agencies and the authorities in which they operate must make a commitment to ensure that technical and business processes effectively protect the privacy of the parties to the transaction from the political, financial and technologically powerful groups that may have the opposite interests.

It is assumed that the authorities will take the same measures as described in Article 3.1 to ensure that companies and registered businesses use known, monitorable accounts in all their transactions. In this case, it is much easier to implement this policy because the entire network is monitored and operated by the regulator, and the regulator can expect to monitor taxable income and distribute the items and distributions in the cash flow statement. Checking the actual transfer that can be audited on the ledger will also bring the same benefits.

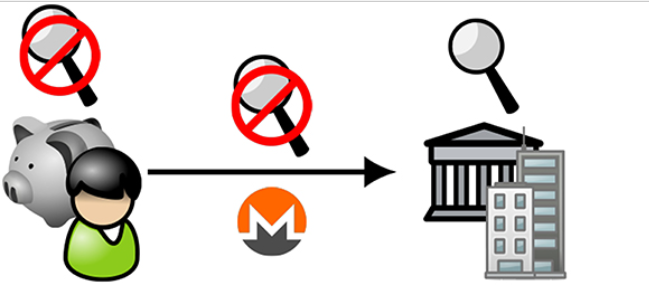

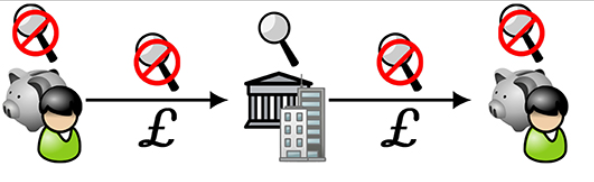

National actors will also recognize another important benefit of this approach. Since all transactions must involve a regulated institution, the kind of transaction described in Figure 7 is not possible, in which private participants exchange value directly through their own private storage. Figure 9 shows how users make payments privately. Users will first receive funds from the registry's account and then remit them to their private store. When she wants to pay a merchant or service provider, she can remit funds to the account that the organization holds on the registry. The distributed ledger's privacy protection features, such as ring signatures, encrypted addresses, encrypted transactions, and any other necessary features that may be developed from time to time, will ensure that when an individual makes a payment, she will not disclose her identity or any information about her previous transaction. , including the transaction she initially received funds.

Figure 9

Figure 9 is a schematic diagram of institutional-mediated private value exchange: private transactions . As shown, the individual receives the funds into her institutional account (the second icon on the left) and transfers it to her private store (the second icon on the right). Unlike Figure 5, these funds may be currency issued by the state (indicated by the pound sign), not the cryptocurrency. When she wants to pay, she must transfer money from her private store to an account held by a regulated agency (the icon on the far right).

By ensuring that no single company gets a large share of any individual transactions in the system, the use of distributed ledgers meets the basic design requirements. Individuals are expected to use their own private stores to trade with many different counterparties through their own regulated outlets, so no intermediary has a global “panopticon” view of all individual transactions.

Since individuals cannot trade directly through their private storage, in order to exchange value, they must trade through a regulated intermediary, as shown in Figure 10. Individuals making transactions may not need to have an account to exchange value with each other. We speculate that regulated intermediaries will charge a certain fee for services. We also show that there is no need to perform the strong recognition of FATF recommendations in the middle, but it may be necessary to have a larger form of identification, such as an attribute-backed certificate indicating that the sender or receiver is eligible. Regulated intermediaries can also provide token blending services to individual groups that meet the “anti-money laundering” standards without having to explicitly ask for their uniform identity.

Figure 10

Figure 10 is a schematic diagram of the private value exchange of institutional intermediaries: intermediary transactions between consumers. Individuals (external icons) wish to trade through their private store rather than through the account of the regulated agency and must trade through a regulated intermediary (center icon).

If implemented successfully, the approach described in this section will provide governments with the same tax and audit benefits as described in Section 3.1, and governments will also be able to implement blacklisting or economic sanctions on target recipient countries. For transactions involving merchants and service providers, individuals will receive the same privacy benefits as described in Section 3.1, and for other transactions, the intermediary's identity requirements can be reduced.

However, there are two major drawbacks to individuals seeking privacy . The first drawback is that individuals need to interact with registered intermediaries before they can pay or receive payments. Another, more serious problem is the issue of mechanisms in the security system that enable people to enjoy private property. Since cryptocurrencies represent checks and balances on state power, we have reason to believe that the privacy characteristics of cryptocurrencies will continue to improve, despite their obvious shortcomings.

If the regulated agency that designs, deploys, and maintains the infrastructure that performs the transaction is required to mark the privacy of its customers, there may be inconsistencies in interest. Customers need to be aware of the actual privacy restrictions of the infrastructure, so for the benefit of the public, confrontational audits need to be conducted from time to time.

Organizations will then need incentives and resources to continually improve the infrastructure and correct any deficiencies on an ongoing basis. A process of accepting new participants will be necessary to ensure that the network remains distributed and will need to meet open standards to ensure that privacy-threatening programs do not develop outside the public eye. There are also a number of implementations that need to be implemented so that sporadic vulnerabilities do not threaten a large portion of the privacy of system users.

It can be said that there is such an incentive between cryptocurrencies because they must compete for business. It remains to be seen whether effective auditing and competition can ensure that the value exchanges that are fully operated by the organization are sufficient to protect the user's private assets.

4 Conclusion

Using the ongoing discussion of paying for the future as a set of trade-offs, we introduce two possible candidate architectures for electronic value exchange that support privacy : cryptocurrencies that support privacy and private value exchanges that support privacy intermediaries .

Both architectures require the design, implementation, deployment, and maintenance of new technologies and the development of regulatory policies for the operation of these technologies. Table 3 summarizes these trade-offs and puts our two expected approaches in context. Cash has many desirable characteristics, such as universality (ie, liquidity of cash, its use does not require a relationship with the registry) and privacy in practice (the serial number on the banknote can be tracked, but is usually not required) . However, it cannot be sent over computer networks and is sometimes used for illegal transactions, including tax evasion. In contrast, modern retail banks require accounts for large-scale monitoring. The most popular cryptocurrencies, such as bitcoin, don't actually evade monitoring, and in some ways they may be easier to track than regular retail transactions. Although research has shown that the goal of promoting the development of cryptocurrency has not been fully realized, cryptocurrencies that implement privacy protection are expected to address these two shortcomings.

table 3

Table 3: Comparison of various electronic payment methods, including new methods proposed.

The various methods of electronic payment have their own advantages and limitations. We hope to promote a more comprehensive dialogue among stakeholders by expounding various compromises and provide a useful framework for discussing future solutions.

We believe that both methods have their status and potential followers, and one approach does not preclude the use of another. Companies that provide services to cryptocurrency users and dealers will find value from the first approach, while companies seeking to promote private, cash-based electronic transactions within a regulated system will find value from the second approach. Accordingly, some regulators may be in trouble due to asset transactions that support value and use beyond their capabilities. As with the first approach, some privacy-conscious individuals may be subject to the operating system described in the second approach. Regulatory financial institutions may be secretly colluding and uncomfortable to undermine the anonymity of customers.

We recommend that the cryptocurrency that systematically supports privacy protection will be stricter than the privacy-protected cryptocurrency without institutional support, primarily because regulators will benefit from the ability to monitor companies and registered companies that use cryptocurrencies. We also suggest that institutional private value exchanges will outperform current modern retail banking, primarily because users will avoid using payment networks and enjoy better privacy expectations in their daily activities. However, neither approach has reached all of the goals of both parties. For example, the ability to conduct transactions without interaction with regulated agencies may be incompatible with the government's ability to prevent illegal use. Similarly, if cryptocurrency governance is exogenous, monetary policy may also be realized, although the likelihood of this happening on a large scale seems remote. However, with the difficult choices for future payments to surface, we believe that recognizing and discussing these trade-offs, as well as commitment to serious privacy and serious regulation, are prerequisites for advancing the interests of all stakeholders.

Author's contribution:

Geoff Goodell is the first author, he conducted research and wrote a thesis. Tomaso Aste directed the study and edited the citation, framework, language, and context of the existing literature.

Conflict of interest statement:

The authors state that the study was conducted without any commercial or financial relationship and that these relationships could be interpreted as potential conflicts of interest.

Geoff Goodell: Graduated from the University of London, a senior researcher and currently an assistant at the University of Oxford's Center for Technology and Global Affairs.

Tomaso Aste: Professor of Complexity Science, Department of Computer Science, University College London. He is a well-trained physicist who has made significant contributions to the study of complex structural analysis, financial systems modeling, and machine learning. He is passionate about the impact of technology on society and is currently focusing on the application of blockchain technology.

Compile: Sharing Finance Neo

We will continue to update Blocking; if you have any questions or suggestions, please contact us!

Was this article helpful?

93 out of 132 found this helpful

Related articles

- Tracking of illegal bitcoin mines on the Dadu River: the mine owner’s investment is back to the original million

- Getting started with blockchain: Ethereum transfer, how to calculate the fee, how to save money?

- Bitcoin has earned more than 120% in the past three months. Is it time for Stud?

- Blockstack, the first project to comply with US SEC regulations, began issuing tokens

- Bitcoin, Ethereum and Cosmos, Polkadot Wheel PK

- Morpheus Labs will provide Dapp developers with efficient development tools based on Wanchain

- Save 75% of bandwidth, make Bitcoin more secure, and core developers retreat for 1 year