An Article Summarizing the Legal Hotspots, Examples, and Controversies in the NFT Field.

Understanding NFTs Exploring Legal Hotspots, Notable Cases, and Ongoing ControversiesAuthor | Inal Tomaev

Translated and published with permission by Wu Shuo

Original article link:

https://medium.com/@inaltom/nft-legal-issues-2022-overview-c90614ed617d

- Disney and Dapper Labs: Bringing Magic to the Blockchain

- NFT Market Returns to Heat A Roundup of the Bestselling NFT Series This Week

- Crypto.com Scores a Hat Trick Team Up with PSG Soccer to Score Early Access to Blvck Paris Fashion Collab NFTs!

This article aims to identify and address the legal issues faced by the NFT industry.

Origin

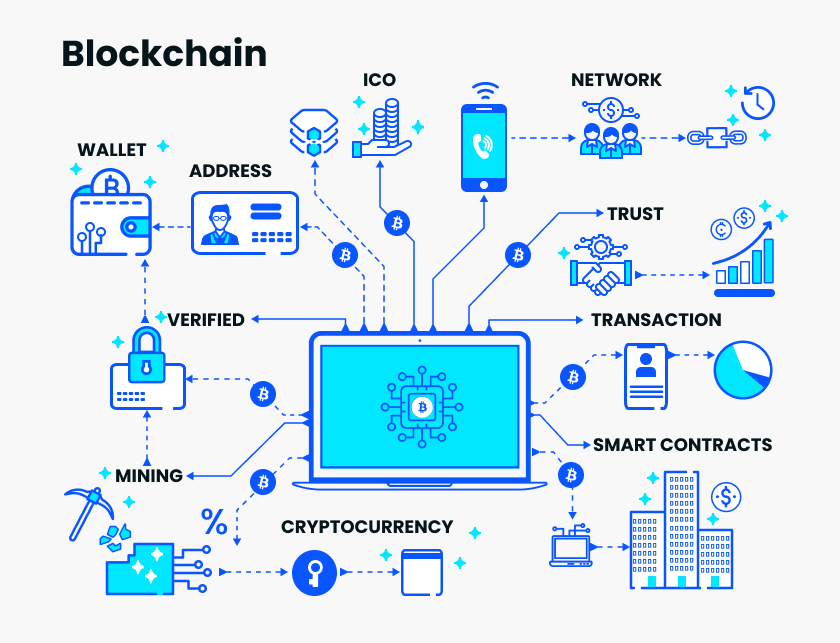

NFTs are encrypted tokens (digital certificates) recorded in a blockchain registry, which can confirm ownership of almost anything in the digital or physical world (such as images and real estate). Each NFT is unique and has its own value due to its association with the asset.

The concept of using NFTs as a way to represent and manage real-world assets on the blockchain can be traced back to Meni Rosenfeld’s article “Overview of Colored Coins,” published on December 4, 2012. In the article, Rosenfeld introduced the concept of “colored coins,” which were similar to Bitcoin but added a “token” element that gave them specific uses or utilities, making them unique. The author suggested that these tokens be used not only in the blockchain but also in applications connecting the real world.

On May 3, 2014, digital artist Kevin McCoy created the first NFT called “Quantum” on the Namecoin blockchain. “Quantum” is a pixelated octagon-shaped digital image that changes colors and pulses like an octopus. This early use of NFT technology became a prototype for the entire digital art field.

From a technical perspective, the available blockchains at the time (primarily Bitcoin) were not designed to be databases for tokens representing asset ownership. The significant development of NFTs began with the emergence and widespread adoption of Ethereum.

It is also important to distinguish between NFTs and the primary assets they represent in three ways:

1. On-chain: All transactions involving NFTs are recorded on a single blockchain and can be easily verified using a blockchain explorer. An example of this is recently sold real estate as an NFT.

2. Off-chain: Transactions are recorded not only on the blockchain but also in a centrally managed database. An unusual example can be found on OpenSea, where a 2,000-pound tungsten cube was sold as an NFT.

3. The legal relationship that exists between on-chain and off-chain is known as “follow-on rights,” where the latter relies on the former and requires a certain degree of rights.

Utility

NFTs are particularly popular in the art world, where the uniqueness of artworks is highly valued. Therefore, NFT owners are often seen as the “chosen ones” in the art world.

However, many people associate NFTs with strange, colorful images that sell for millions of dollars. In fact, NFTs can represent a wide range of assets, including digital and physical ones, which hold value in both virtual and real-world contexts.

NFTs should not be limited to the realm of crypto art. More accurately, NFTs are a technology tool that can provide new opportunities in both worlds.

Here are some examples of NFT usage:

● Digital Art

One of NFT’s main applications is in the art and collectibles field. Traditional art, such as paintings, holds value because of its uniqueness – created with unique techniques and materials. Digital files are easily replicable, but NFTs provide a way to prove ownership of unique digital or physical assets. NFTs offer creators a new way to monetize their digital art and provide collectors with a new way to own and trade unique items. NFT platforms may even offer the possibility of automatic royalties for future sales to artists, depending on the platform (platform examples – OpenSea, Rarible).

Representative examples: Art Blocks, Murakami Flower Seeds

● PFP (Profile Picture)

NFTs associated with PFP or “Profile Pictures” are often found on Twitter, linked to specific accounts. If a PFP is verified on Twitter, the user may receive special avatar ornaments or badges. PFP ownership can also grant access to certain communities and the games or other products created by those communities.

Representative examples: BAYC, CryptoPunks

● Virtual Land

These NFTs represent digital land areas owned by users in metaverse platforms, granting owners the ability to use the land for various purposes such as advertising, communication, gaming, work, or renting.

Representative examples: The Sandbox, NFT Worlds

● Gaming

Representing objects in games such as avatar incarnations, weapons, animals, and land.

● Memberships

NFTs can also be used to solve user privacy and data handling issues. They eliminate the need to remember multiple platform passwords and can be resold on secondary markets for profit.

Representative examples: Proof, Premint

● Community NFTs

NFTs can also provide benefits when participating in online and offline social activities.

Representative examples: VeeFriends

● Music

NFTs representing digital content such as music or videos often differentiate the rights of holders and creators. In most cases, users gain ownership of the token itself, granting them the right to sell, transfer, or otherwise dispose of the token. However, any intellectual property associated with the token remains with the creator, and token holders may only have the right to receive partial royalties as co-investors from streaming platforms.

Examples: Royal, Rocki, Sound

● Brand

The popularity of NFTs has led many brands to research the potential uses of NFTs as digital assets and their integration with web3.

Examples: Adidas, Nike (acquired one of the most famous NFT studios – RTFKT)

● Accounts/Domain Names

In web 2.0, traditional accounts or domain names do not belong to users in the true sense. For example, Twitter owns all account information and has the authority to revoke or delete accounts. NFTs can be used to create decentralized, blockchain-based account systems, with each account verified by a digital certificate.

Examples: ENS, UnstopLianGuaible

The uniqueness of NFTs can also be applied in other fields:

● Identification tools (such as SoulBound Token)

NFTs can serve as universal IDs for various digital services and databases, such as voting systems, attendance tracking, medical records and certificates, and even as a way to identify anonymous individuals in legal proceedings.

● Real Estate

NFTs can represent ownership of real estate assets.

● Logistics

NFTs can be used to track and verify the movement of goods in supply chains.

Legal Status

From a legal perspective, NFTs can be complex objects with different legal characteristics depending on the specific circumstances. This may subject NFTs to various regulatory constraints in different jurisdictions, including taxation, licensing, and other requirements.

Here is an overview of the legal status of NFTs in major jurisdictions:

● United Kingdom

In the UK, there are no specific regulations for NFTs, and they are considered as a form of cryptographic asset. The Financial Conduct Authority distinguishes three types of tokens:

○ Securities: Tokens that grant rights and obligations specified in investment agreements, including stocks, deposits, insurance, etc. Regulated under the Financial Services and Markets Act 2000.

○ E-money: Electronic stored monetary value subject to anti-money laundering regulations.

○ Most NFTs do not fall into the above categories and therefore are not regulated.

● European Union

Similar to the UK, the European Union does not have specific regulations or legal definitions for NFTs, and there is no agreed regulatory regime among member states.

On October 5, 2022, the European Commission published the Markets in Crypto-assets Regulation (MiCA), which is expected to become the final version of MiCA, subject to further agreement by the Parliament in 2023 and does not include NFTs.

However, the proposed regulation will explicitly apply to NFTs that confer certain rights to the owners, such as rights to financial instruments, profit-sharing rights, or other interests. In these cases, NFTs may be considered securities. NFTs may also be subject to legislation in EU member states.

● China

In China, cryptocurrencies are prohibited, but individuals can engage in NFT transactions. Currently, China does not have specific laws or regulations for NFTs. However, on April 13, 2022, the China Internet Finance Association, China Securities Industry Association, and China Banking Association jointly launched an initiative to prevent financial risks associated with NFTs. While this initiative is not a regulatory action under Chinese law, it reflects the government’s overall attitude towards NFTs.

According to the initiative, NFTs are not considered cryptocurrencies or virtual currencies. However, the following points should be followed:

○ NFTs should not include securities, insurance, credit, precious metals, or other financial assets.

○ The unique and non-fungible nature of NFTs should not be compromised through property subdivision or other means.

○ Centralized trading should not be conducted.

○ Virtual currencies such as Bitcoin, Ether, USDT, etc., should not be used as pricing and settlement tools for issuing and trading NFTs.

○ Individuals involved in NFT issuance, buying, selling, and purchasing should undergo real-name authentication, and customer identity information and NFT transaction records should be properly secured.

○ Active cooperation is required in anti-money laundering efforts.

○ Direct or indirect investment in NFTs should not be made, and financial support for NFT investments should not be provided.

● United Arab Emirates

The regulation of NFTs and crypto assets in the UAE is generally at the level of free economic zones. For example, the Abu Dhabi Global Market (ADGM) recently issued a consultation paper titled “Improving Capital Markets and Virtual Assets.” ADGM believes that companies need to obtain approval from the financial regulatory authority of the free zone to trade NFTs, and NFTs may be subject to ADGM’s anti-money laundering and sanction regulations. These proposals are still in the consultation stage, but market participants should take them into consideration.

The Dubai Multi Commodities Centre (DMCC) has introduced a license for NFT markets. Additionally, NFTs may be subject to the “Crypto Asset Rules,” which apply to cryptographic assets that are securities or traded on exchanges. Anti-money laundering requirements may be applicable depending on the nature of the underlying assets.

● Singapore

The Monetary Authority of Singapore (MAS) has announced that it will not regulate the NFT market as it sees it as still in its nascent stages and does not want to regulate people’s investments. However, under Singapore law, if an NFT exhibits characteristics of capital market products regulated under the Securities and Futures Act (SFA), it will be subject to MAS regulatory requirements.

For example, if an NFT represents rights to a portfolio of stocks listed on a stock exchange, it will be subject to requirements similar to other collective investment schemes, such as securities issuance, licensing, and commercial conduct.

Similarly, if an NFT exhibits characteristics of digital payment tokens under the Payment Services Act (PSA), special restrictions and obligations may be imposed on sellers of such NFTs.

● United States

Currently, there are no specific regulations in the United States for NFTs, but they should be considered as crypto assets. Consideration is being given to the Responsible Financial Innovation Act (RFIA), which would create the first comprehensive regulatory framework for digital assets in the United States.

The bill classifies most digital currencies as commodities, which means they would be regulated by the Commodity Futures Trading Commission (CFTC). The RFIA provides clear standards for determining when digital assets are considered commodities and when they are considered securities.

Before this, the nature of NFT as a regulated object was determined by the US Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC), which typically applies the “Howey test”. The current method of regulating all cryptocurrencies is reflected in the comments of SEC Chairman Gary Gensler, who stated that “securities laws should be applicable to cryptocurrencies”.

In general, the practices of all analyzed jurisdictions are similar: we are not yet sure what NFT is, but if they resemble regulated objects (commodities, currency, securities), we will not hesitate to regulate them.

In addition, there is a trend to strengthen the regulation of cryptocurrencies and NFTs (the FTX case provides another reason), and it is expected that the United States will take the lead in this work in 2023.

Copyright

Attention, spoilers!

Ownership of an NFT does not automatically grant copyrights to the object behind the NFT.

According to Section 102 of the US Copyright Act, protection is automatic for “original works of authorship fixed in any tangible medium of expression” and belongs to the author once the original expression is fixed.

This includes eight categories of works: literary works; musical works, including any accompanying words; dramatic works, including any accompanying music;

pantomimes and choreographic works; pictorial, graphic, and sculptural works; motion pictures and other audiovisual works; sound recordings and architectural works.

NFT images belong to the category of pictorial works.

Copyright protection grants the holder the rights to reproduce, distribute, publicly display, perform, and create derivative works based on the original work, as well as the right to prevent others from doing so. When purchasing an NFT, the authenticity of the work can be confirmed through the blockchain.

However, it should be noted that purchasing an NFT does not automatically grant copyrights to the object behind it, and the buyer is responsible for ensuring that the work does not infringe any existing copyrights.

Let me emphasize this. One benefit of purchasing an NFT is that the authentication process is done on the blockchain. When you purchase an NFT from a reputable artist, the authenticity of the NFT will be verified through the association between the original seller and the artist (the marketplace is responsible for verifying this). You can trust that the NFT you purchase is genuine, regardless of how many times it has been resold, because everything can be tracked using a blockchain explorer. However, the blockchain will not provide information on whether the NFT you purchased is a replica of another artist’s copyrighted work.

According to Section 504 of the US Copyright Act, selling infringing works, even if unintentional, automatically subjects the seller to actual damages and/or statutory damages ranging from $750 to $30,000 per infringement. If the infringement is found to be willful, the damages per infringement increase to $150,000. It should be noted that this is per infringement, meaning that the quantity of NFTs involved in a sale could result in multiple infringements.

Currently, there are some complexities surrounding the transfer of rights through NFTs. Although NFTs and copyrights are separate entities, the transfer of one may also involve the transfer of the other. For example, the terms and conditions of the Bored Apes Yacht Club state that “when you purchase an NFT, you will fully own the underlying art of the Bored Ape.” This indicates that ownership of the NFT includes ownership of the underlying artwork.

One interesting aspect of NFTs is that the token can be separated from the rights it represents. For example, the owner of a Bored Ape NFT (including the token and related artwork) may decide to transfer the image rights used on a T-shirt to person A, while selling the NFT itself to person B.

According to the Bored Ape rules, the transfer of an NFT should include all associated rights. This means that person A would be in violation by doing so, as person B did not transfer the rights to use the T-shirt image to person A. However, it could also be understood that person B is not involved in the transaction between person A and the owner of the rights, therefore there is no infringement. If person B also uses the image from the Bored Ape NFT to create a T-shirt, it would imply the same logic.

This issue could potentially be resolved by considering the rights associated with NFTs as real property rights, where ownership burdens follow the object. I have found only one project that adopts this approach. World of Women operates under this model and is governed by French law. However, this solution may not fully address the problem.

Under section 204(a) of US Copyright Law, “a transfer of copyright ownership, other than by operation of law, is not valid unless an instrument of conveyance or a note or memorandum of the transfer, is in writing and signed by the owner of the rights conveyed or such owner’s duly authorized agent.” This requirement applies to physical documents as well as electronic agreements, such as those involving the “click to agree” options.

This only applies to the initial purchase, when the owner in the above example completes the first transaction. Afterwards, on the blockchain, no one is checking any checkboxes or signing any documents. That’s a separate issue. If you’re interested, you can read a great article on the relationship between smart contracts and legal contracts. The logic goes like this:

● The owner of an NFT is also the copyright holder of the content behind the NFT.

● The owner of an NFT transfers the NFT through a smart contract, which, unless specified otherwise, does not affect the content behind the NFT.

● According to the law, the transfer of rights requires a separate document.

● This document must be signed by the copyright holder.

An important aspect of copyright is understanding the concept of derivative works. In my opinion, derivative works can be even more valuable in some ways than the original piece. Let me explain: the value of the original often depends on the network effect of the quantity of derivative works, in other words, the true uniqueness of what the original creator has innovated can be “measured” through the viral spread of derivative works.

From a legal perspective, a derivative work is a work that is based on one or more existing works. This includes translations, musical arrangements, stage adaptations, film adaptations, recordings, art reproductions, abridgments, or any other form of processing, transformation, or adaptation.

The copyright of derivative works only applies to the parts that are distinct from the existing material introduced by the derivative work author, and does not imply any exclusive rights to the existing material. There are two key criteria for identifying derivative works: originality and legality.

Originality

Derivative works must be original and able to obtain copyright on their own. This requirement helps ensure that the author of the derivative work contributes a significant amount of original expression to the final product. If the derivative work is merely a copy of the original and contains little or no original content, it may not be considered a derivative work and therefore does not meet the criteria for copyright protection.

Legality

The legality of creating a derivative work is also important. If copyrighted material is used without the permission of the copyright owner, copyright protection does not apply to any part of the derivative work that uses the original content illegally. To create a derivative work that can obtain copyright and potentially be sold, permission must be obtained from the copyright owner of the original work.

The ability to create derivative works is often considered a key factor in the success of the Bored Apes Yacht Club series. The Rules of Bored Apes grant unrestricted global licenses to use, copy, and display the acquired artwork for the creation of derivative works, including for commercial purposes. However, these same rules also stipulate that when purchasing an NFT, the buyer fully owns the underlying Bored Ape artwork. This creates a contradiction because if the buyer already owns the artwork, it is unclear which rights are transferred for commercial use. Perhaps they are attempting to emphasize the independent right to create derivative works, but they have not effectively done so.

It is worth noting that copyright law treats NFTs in the same way as traditional artworks because in this case, copyright takes precedence over the blockchain. When artists create new artworks, they automatically obtain the copyright and some proprietary rights to the work. These rights include the right to attribution, the right to the author’s name, and the right to the integrity of the work, among others, which cannot be transferred. Other rights, such as the right to copy, create derivative works, or distribute copies of the work, can be the subject of a contract and transferred to others for commercial purposes. To avoid any potential conflicts, it is crucial to define the quantity of rights transferred in NFT transactions.

To understand how copyright infringement issues are currently being resolved in the context of NFTs, it would be helpful to look into some public cases.

● Benjamin Ahmed and “Weird Whales”

A 12-year-old programmer named Benjamin Ahmed sold 3,350 computer-generated “Weird Whales” NFTs for nearly £300,000, but later discovered that the project’s graphics were directly copied from another project. The original author of the graphics has not come forward.

● Quentin Tarantino vs. Miramax

Director Quentin Tarantino announced that he will sell seven NFTs related to the 1994 film “Pulp Fiction.” The NFTs will include the “uncut original handwritten screenplay” from the film and the director’s “exclusive personal commentary.” The film’s distributor, Miramax, has filed a lawsuit claiming that he does not have the legal right to create and sell NFTs and that he has misled consumers about Miramax’s involvement in creating the NFTs. The case is currently under review.

● Hermès vs. Mason Rothschild

The French fashion company Hermès is suing California artist Mason Rothschild over his NFT project “MetaBirkin,” which depicts Hermès’ iconic Birkin bags and its trademarks. Hermès argues that Rothschild has misappropriated the Birkin trademark and has profited from the sale of over 100 digital collectibles. The case is currently under review.

● Nike vs. StockX

In February 2022, Nike filed a lawsuit against online sneaker company StockX for selling its “Vault” NFT without permission. Nike claims that StockX intentionally used its trademark to create NFTs without authorization and misled consumers about Nike’s involvement in creating NFTs. The case is currently under review.

● SpiceDAO

Cryptocurrency project SpiceDAO made headlines after paying $3.5 million to acquire an unpublished script manuscript of the movie “Dune” with the intention of creating NFTs based on it, only to later discover that the acquisition did not include those rights.

● CryptoPunk vs. CryptoPhunk

This case involves two sets of punk pixel images: CryptoPunk, which is original, and CryptoPhunk, which is a counterfeit. The creator of CryptoPunk, Larva Labs, notified NFT marketplace OpenSea of the copyright infringement and had the CryptoPhunk series removed from the website under the Digital Millennium Copyright Act.

● HitPiece

The website HitPiece was accused of selling NFTs featuring the works of many musicians without permission. The website was found to be selling NFTs featuring content from Disney, Nintendo, John Lennon, and many other companies. The original website was shut down, but developers quickly relaunched it. As far as I know, the situation did not escalate into a legal case.

In order to combat copyright infringement in the NFT space, online art gallery DeviantArt and California startup Optic are using image recognition technology and machine learning to analyze smart contracts and identify infringing NFTs in the market. Optic works closely with NFT marketplace OpenSea. It seems that proving the originality of NFT projects will be a trend in 2023.

Licensing

In the process of creating NFTs, such as PFP collections, there can be several participants:

● Project Owners

The conceptual authors, producers, founders, and visionaries of the project. They are the ones who initiate the project and bring everyone together.

● Creators/Artists

The creative individuals who breathe life into the project, whether they are the original creators or hired experts.

● Investors

The buyers of the NFTs.

● Community

This typically includes anyone involved in the project, from the owners to subscribers of social networks. This can include creators, authors of derivative works, sponsors, initiators, influencers, and others who are interested in the project and may contribute to its development.

Market

● NFT trading platform.

These parties need to address issues related to rights transfer, such as the ability to create derivatives, imitate, merchandise, and resell NFTs.

To address these issues, NFT marketplace participants have recognized the need for clear rules to govern intellectual property and have proposed their own NFT licensing schemes.

In 2018, Dapper Labs (known for their work on CryptoKitties and NBA Top Shot) offered the first known NFT license, and in August 2022, a16z VC Fund released their vision for NFT licensing. During the summer of 2022, knowledge sharing licenses were widely used in NFT sales. a16z wrote a great article explaining why NFT creators choose CC0 tools (Creative Commons has multiple license variants) to transfer rights.

By accepting a CC0 license, the copyright holder agrees to waive their copyright and related rights to the fullest extent permitted by law. Therefore, the work is effectively “dedicated” to the public domain. If for any reason it is not possible to achieve this relinquishment of rights, CC0 will serve as a license granting the public unconditional, irrevocable, non-exclusive, free rights to use the work for any purpose.

This means that NFTs governed by CC0 have no restrictions on their commercialization or any other way owners see fit to use them. Owners of CC0 governed NFTs are on equal footing with the creators in terms of owning the NFT collection.

However, since no one owns the artwork under a CC0 license, it also means that anyone (even those who don’t own the NFT) can use the artwork for any purpose, including creating NFTs. This creates a paradox – if you cannot prevent others (even non-owners of your NFT) from using artwork related to your NFT, why spend resources creating NFTs? The only reason to do so is to promote the ideology of NFTs, not for economic benefit.

In fact, there are several main options for determining the scope of rights transferred through NFTs, which can be classified as follows:

● Buyer does not acquire any rights other than the right to display the NFT

● Buyer acquires limited commercial rights related to the NFT they own

● Buyer acquires full commercial rights related to the NFT they own

● Copyright owners may waive their exclusive rights to the extent permitted by law.

Another issue with NFT licensing agreements (aside from determining the scope of transfer rights) is the copyright owner’s asymmetric control over the license. The copyright holder can modify or revoke NFT licenses of the NFT owners at their own discretion, without any notice, if they believe the license agreement has been violated or for any other reason, or even without any reason at all. This ability to change the license agreement at any time may be a major concern for the entire NFT industry, as the rights of every NFT owner can be unilaterally restricted or revoked.

Considering the various options for determining restrictions on NFT transfer rights, I suggest that NFT creators specifically consider current and potential issues in the industry and discuss these issues with the community in the spirit of web3. After all, in this industry, power lies with the community. Only in this way can they formally determine how licensing will be related to their NFTs and ensure the possibility of excluding unilateral changes to the license agreement terms.

Dispute Resolution

The NFT industry is still too new, and there aren’t many legal precedents to analyze. However, the rules of intellectual property law can and should apply to disputes regarding the author’s identity and the use of someone’s intellectual property when creating an NFT.

Courts may be interested in several key questions:

● Is there evidence of using someone else’s intellectual property?

● Has the person claiming copyright infringement proven their identity as the author?

● Was there any harm?

● What was the infringer’s intent?

● What specific actions did the infringer take in response to the infringement, and what were the results?

There may be more questions, but these are enough to understand the logic of the court. The answers to these questions will help the court distinguish between profit-related punishable acts and other actions, and the judge may also consider the “fair use doctrine” in their decision. This doctrine, established by English and American law in the 18th to 19th centuries, allows for limited use of someone else’s copyrighted material without permission.

The doctrine includes four factors that the court needs to consider:

● The nature of the copyrighted material

To prevent private ownership of works that should belong in the public domain, the court needs to understand the origin of the idea. In this case, known facts and ideas are not protected by copyright, only their specific expression (such as descriptions, methods, or schemes) is protected. If known information is reinterpreted in this way, it may be considered as expressing the author’s identity.

● The amount and substantiality

These two factors should be considered together. The court first determines the quantity of the disputed information related to the original work (for example, fragments in text or photos). Generally, the less relative to the overall use, the more likely the use will be considered fair. However, the importance of the disputed information also plays a certain role, and usually this second factor is more important legally.

● The effect of the infringement

If the use impairs the copyright holder’s ability to profit from the original work and is used as a substitute demand, it is considered unfair.

The court may also consider additional standards specific to the case to provide greater clarity.

If we apply the fair use doctrine to the situation between CryptoPunk and CryptoPhunk, it will serve as the basis for the court’s judgment. It would be interesting to see how the court rules, but since OpenSea resolved the issue internally, we can only speculate on how the court might have handled the case.

The anonymous infringing creator of CryptoPhunk stated in an open letter that the purpose of creating this series was “to imitate and satirize” (falling under the “purpose & character of use” factor of the doctrine). However, considering other factors, this infringing creator seems to:

● Failure to fully transform the original work (first criterion)

● Use of materials that are already in the public domain (second criterion)

● Use of a large number of original ideas with only minor changes (third criterion)

● Significant impact on the reputation and income of the copyright holder (first and fourth criteria)

● Knowledge of the original author (additional criterion)

Given these factors, OpenSea’s solution seems reasonable.

Conclusion

While there is an open principle, the industry needs rules to function properly. Players who take the NFT industry seriously and plan to stay in the industry long-term will quickly adapt to these rules and understand that these rules are in place to protect everyone. Understanding the legal status of future digital assets, the methods of transfer, and the rights they encompass will help create a more reliable industry for NFT creators.

As the industry evolves, controversial situations may increase. Potential areas of dispute in the NFT field include: licensing fees; disputes over the scope of transfer rights; NFT theft; counterfeiting (confusingly similar) NFTs; taxation; advertising and promotion; hacking attacks; personal data; identifying violators; completing transactions using NFTs as collateral; responsibility in the NFT market.

We will continue to update Blocking; if you have any questions or suggestions, please contact us!

Was this article helpful?

93 out of 132 found this helpful

Related articles

- G2A Launches Geekverse The Ultimate NFT Marketplace for Gaming Enthusiasts

- Forget Web2 Woes Traditional Web2 Security Issues Caused 46.5% Loss in Web3 Fund; Blockchain Gaming Surpasses $1.5 Billion Investment in 2023!

- The NHL Joins the Digital Collectibles Bandwagon, Better Late than Never!

- Disney enters the NFT market and collaborates with Dapper Labs to launch the digital badge collection platform Pinnacle.

- From Mutant Ape Copycat NFTs to Courtroom Drama Mastermind behind $3M Fraud Scheme Pleads Guilty

- Disney and Dapper Labs Spark Digital Magic with Epic NFT Platform

- Disney and Dapper Labs: A Magical Partnership in the NFT World