TaxDAO’s Response to the US Senate Finance Committee on the Issue of Taxation of Digital Assets

TaxDAO's Response to US Senate Finance Committee on Taxation of Digital AssetsAuthor: TaxDAO

On July 11, 2023, the U.S. Senate Finance Committee issued a letter seeking opinions from the digital asset community and other stakeholders on how to appropriately handle transactions and income from digital assets under federal tax law. The open letter raised a series of questions, including whether digital assets should be valued at market prices and how digital asset lending should be taxed. Based on the principle that tax policies should be loose and flexible, TaxDAO has provided corresponding responses to these questions and submitted a response document to the Finance Committee on September 5th. We will continue to follow up on the progress of this important issue and look forward to close cooperation with all parties. Welcome everyone to pay attention, communicate, and discuss!

The following is the full response from TaxDAO:

TaxDAO’s Response to the U.S. Senate Finance Committee on Digital Asset Taxation Issues

- US House Financial Services Committee Regulatory agencies should cooperate with Congress to establish regulatory rules.

- Recognition of the Property Nature of Virtual Currency and Issues Regarding the Disposal of Assets Involved in Cases

- DAC8 enters the stage of opinion review, the EU’s encrypted tax regulation is coming

September 5, 2023

To the Finance Committee:

TaxDAO is pleased to have the opportunity to respond to the key issues in the intersection of digital assets and tax law raised by the Finance Committee. TaxDAO was founded by the former Chief Tax Officer and Chief Financial Officer of a blockchain industry unicorn and has handled hundreds of financial and tax cases in the Web3 industry with a cumulative amount of billions of dollars. It is a rare institution that is extremely professional in both Web3 and finance and taxation. TaxDAO hopes to help the community better deal with tax compliance issues, bridge the gap between tax regulation and the industry, and conduct basic research and construction to assist the industry’s future compliance development in the current early stage of tax regulation in the industry.

We believe that in the current booming era of digital assets, loose and flexible tax policies will be beneficial to the industry’s growth. Therefore, while regulating digital asset transactions for tax purposes, it is necessary to consider the simplicity and convenience of tax operations. At the same time, we also recommend a unified definition of digital assets to facilitate regulation and tax operations. Based on this principle, we provide the following response.

We look forward to working with the Finance Committee and supporting positive changes in digital asset taxation to promote sustainable economic development.

Sincerely,

Leslie TaxDAO Senior Tax Analyst

Calix TaxDAO Founder

Anita TaxDAO Head of Content

Jack TaxDAO Head of Operation

1. Traders and Dealers Valuing at Fair Market Value (IRC Section 475)

a) Should traders of digital assets be allowed to value at fair market value? Why?

b) Should dealers of digital assets be allowed or required to value at fair market value? Why?

c) Should the answers to the above two questions depend on the type of digital assets? How to determine if a digital asset is actively traded (as per IRC Section 475(e)(2)(A))?

Overall, we do not recommend that traders or dealers of digital assets value at fair market value. Our reasons are as follows:

First, the characteristic of actively traded crypto assets is that their prices fluctuate greatly, therefore, the tax consequences of valuing at fair market value would increase the taxpayer’s burden.

Under the scenario of valuing at market price, if a taxpayer fails to convert cryptocurrency before the end of the tax year, it may result in the disposal price of the cryptocurrency being lower than the tax liability. (For example, if a trader purchases 1 Bitcoin on September 1, 2023, at a market price of $10,000, and the market price of Bitcoin on December 31, 2023, is $20,000, and the trader sells the Bitcoin on January 31, 2024, at a market price of $15,000. At this point, the trader only gains $5,000 but recognizes a taxable income of $10,000.)

However, if the trader incurs losses on the same digital asset after recognizing the taxable income, the losses can be offset against the recognized taxable income, or the market price valuation method can be used. However, this accounting method will increase tax operations and is not conducive to promoting transactions. Therefore, we do not recommend traders or exchanges of digital assets to value at market price.

Secondly, it is difficult to determine the (average) fair market value of cryptocurrency. Active trading of cryptocurrencies often occurs on multiple trading platforms, such as Bitcoin being able to be traded on platforms such as Binance, Huobi, Bitfinex, etc. Unlike securities trading, which only has one securities exchange, the prices of cryptocurrencies vary on different trading platforms, making it difficult for us to determine the fair value of cryptocurrencies through “virtual sales”. In addition, inactive traded cryptocurrencies do not have a fair market value, so they are also not suitable for market price valuation.

Finally, in an emerging industry, tax policies are often simple and stable to encourage industry development, and the cryptocurrency industry is exactly an emerging industry that needs encouragement and support. The market price valuation method for tax treatment undoubtedly increases the administrative costs for traders and exchanges, which is not conducive to industry growth. Therefore, we do not recommend adopting this tax policy.

We recommend that the cost basis method continue to be used to tax traders and exchanges of cryptocurrencies. This method has the advantages of simplicity and policy stability and is suitable for the current cryptocurrency market. At the same time, we believe that since the cost basis method is used for taxation, it is not necessary to consider whether the cryptocurrency is actively traded (according to IRC Section 475(e)(2)(A)).

2. Trading Safe Harbor (IRC Section 864(b)(2))

a) Under what circumstances should the policy behind the trading safe harbor (encouraging foreign investment in US investment assets) apply to digital assets? If these policies should apply to (at least part of) digital assets, should digital assets fall within the scope of IRC Section 864(b)(2)(A) (safe harbor for securities trading) or IRC Section 864(b)(2)(B) (safe harbor for commodities trading)? Or should it depend on the regulatory status of specific digital assets? Why?

b) If a new, separate trading safe harbor can apply to digital assets, should additional restrictions apply to commodities that meet the trading safe harbor conditions? Why? If additional restrictions should apply to commodities in this new trading safe harbor, how should terms such as “organized commodity exchange” and “regularly carried out” be interpreted in different types of digital asset exchanges? (As described in IRC Section 864(b)(2)(B)(iii))

The Safe Harbor Rule does not apply to digital assets, but this is not because digital assets should not enjoy tax benefits, but because of the nature of digital assets themselves. One important attribute of digital assets is their borderless nature, which means that it is difficult to determine the jurisdiction of a large number of digital asset traders. Therefore, it is difficult to determine whether a digital asset transaction belongs to the “transaction conducted in the United States” referred to in the Safe Harbor Rule.

We believe that the tax treatment of digital asset transactions can be based on the status of the resident taxpayer. If the trader is a resident taxpayer of the United States, he or she will be taxed according to the rules of resident taxpayers. If the trader is not a resident taxpayer of the United States, there will be no tax issues in the United States, and the Safe Harbor Rule does not need to be considered. This tax treatment method avoids the administrative cost of determining the location of the transaction, making it more convenient and beneficial to the development of the encryption industry.

3. Handling of digital asset lending (IRC Section 1058)

a) Please describe the different types of digital asset lending.

b) If IRC Section 1058 clearly applies to digital assets, will companies that allow customers to lend digital assets develop standard lending agreements to comply with the requirements of this provision? What challenges does compliance with this provision bring?

c) Should IRC Section 1058 include all digital assets or only a subset of digital assets, and why?

d) If digital assets are lent to a third party and a hard fork, protocol change, or airdrop occurs during the loan period, is it more appropriate for the borrower to recognize income in such transactions, or for the lender to recognize income subsequently when the asset is returned? Please explain.

e) Are there other transactions similar to hard forks, protocol changes, or airdrops that may occur during the loan period? If so, please explain whether it is more appropriate for the borrower or the lender to recognize income in such transactions.

(1) Digital Asset Lending

The operation principle of digital asset lending is that a user provides their own cryptocurrency to another user and charges a certain fee. The exact way of managing loans varies depending on the platform. Users can find cryptocurrency lending services on centralized and decentralized platforms, and the core principles of both remain the same. Digital asset lending can be divided into several types based on its nature:

Collateralized loans: It requires the borrower to provide a certain amount of cryptocurrency as collateral in order to obtain a loan of another cryptocurrency or fiat currency. Collateralized loans generally need to go through centralized cryptocurrency trading platforms.

Flash loans: It is a new type of lending method that has emerged in the decentralized finance (DeFi) field. It allows borrowers to borrow a certain amount of cryptocurrency from a smart contract without providing any collateral, and repay it in the same transaction. “Flash loans” utilize smart contract technology and have “atomicity”, which means that the steps of “borrow-transaction-repay” must either all succeed or all fail. If the borrower is unable to repay the funds at the end of the transaction, the entire transaction will be revoked, and the smart contract will automatically return the funds to the lender, ensuring the safety of the funds.

The provisions similar to IRC 1058 should apply to all digital assets. The purpose of IRC 1058 is to ensure that taxpayers who issue securities loans maintain similar economic and tax conditions as when no loans are issued. Similar provisions are also needed in digital asset lending to ensure the stability of traders’ financial conditions. The UK’s latest consultation draft on DeFi, “General Principles,” states: “The staking or lending of liquidity tokens or of other tokens representative of rights in staked or lent tokens will not be seen as a disposal.” This disposal principle is consistent with the disposal principle of IRC 1058.

We can make corresponding provisions for digital asset lending similar to the current IRC 1058(b). As long as a digital asset lending transaction meets the following four conditions, there is no need to recognize income or loss:

① The agreement must stipulate that the transferor will recover the same digital assets as transferred when the agreement expires;

② The agreement must require the transferee to pay the transferor all the interest and other income equivalent to what the digital asset owner is entitled to during the term of the agreement;

③ The agreement must not reduce the transferor’s risk or profit opportunities in transferring the digital assets;

④ The agreement must comply with other requirements specified by the Minister of Finance through regulations.

It should be noted that applying provisions similar to IRC 1058 to digital assets does not mean that digital assets should be considered securities, nor does it mean that digital assets follow the same tax treatment as securities.

After applying provisions similar to IRC 1058 to digital assets, centralized lending platforms can draft corresponding lending agreements for traders based on the regulations. As for decentralized lending platforms, they can meet the corresponding provisions by adjusting the implementation of smart contracts. Therefore, the application of this provision will not have a significant economic impact.

(2) Recognition of Income

If a hard fork, protocol change, or airdrop occurs during the loan period of digital assets, it is more appropriate for the borrower to recognize income in such transactions for the following reasons:

First, according to trading customs, the income from forks, protocol changes, and airdrops is attributed to the borrower, which aligns with the actual situation and contract terms of the digital asset lending market. Generally, the digital asset lending market is a highly competitive and free market where lenders and borrowers can choose suitable lending platforms and conditions based on their interests and risk preferences. Many digital asset lending platforms explicitly state in their service terms that any new digital assets generated from hard forks, protocol changes, or airdrops during the loan period belong to the borrower. This can avoid disputes and protect the rights of both parties.

Second, US tax law stipulates that when a taxpayer receives new digital assets due to a hard fork or airdrop, the fair market value of those assets should be included in taxable income. This means that when borrowers receive new digital assets due to forks or airdrops, they need to recognize income when they gain control and recognize gains or losses when selling or exchanging them. Lenders, on the other hand, do not receive new digital assets, so they do not have taxable income or gains or losses.

Third, protocol changes may cause changes in the functionality or attributes of digital assets, affecting their value or tradability. For example, protocol changes may increase or decrease the supply, security, privacy, speed, fees, etc. of digital assets. These changes may have different effects on borrowers and lenders. Generally speaking, borrowers have more control and risk exposure to digital assets during the loan period, so they should enjoy the benefits or losses brought by protocol changes. Lenders can only regain control and risk exposure to digital assets when the loan matures, so they should recognize the gains or losses based on the value at the time of repayment.

In summary, if digital assets are lent to a third party and there is a hard fork, protocol change, or airdrop during the loan period, it is more appropriate for the borrower to recognize the income in such transactions.

4. Wash Sale Transactions (IRC Section 1091)

a) Under what circumstances would a taxpayer consider the economic substance doctrine (IRC Section 7701(o)) to apply to wash sale transactions involving digital assets?

b) Are there best practices for reporting wash sale equivalent transactions involving digital assets?

c) Should IRC Section 1091 apply to digital assets? Why?

d) Does IRC Section 1091 apply to assets other than digital assets? If so, what types of assets?

Regarding this set of questions, we believe that IRC Section 1091 does not apply to digital assets, and our reasons are as follows: First, the liquidity and diversity of digital assets make it difficult to track corresponding transactions. Unlike stocks or securities, digital assets can be traded on multiple platforms and there are many types and varieties. This makes it difficult for taxpayers to track and record whether they have purchased the same or very similar digital assets within 30 days. In addition, due to price differences and arbitrage opportunities between digital assets, taxpayers may frequently transfer and exchange their digital assets between different platforms, which also increases the difficulty of enforcing wash sale rules.

Second, it is difficult to determine the boundaries of concepts such as “same” or “very similar” for certain types of digital assets. For example, Non-Fungible Tokens (NFTs) are considered unique digital assets. Consider the following scenario: a taxpayer sells an NFT and then purchases a similarly named NFT from the market. Whether these two NFTs are considered the same or very similar digital assets is legally ambiguous. Therefore, to avoid such issues, IRC Section 1091 may not apply to digital assets.

Finally, the fact that IRC Section 1091 does not apply to digital assets does not create significant tax issues. On the one hand, the cryptocurrency market is characterized by rapid value fluctuations and frequent conversions within a short period of time, resulting in investors holding cryptocurrencies for “extremely long periods” less frequently. On the other hand, the prices of mainstream cryptocurrencies in the cryptocurrency market often rise and fall together. Therefore, the application of wash sale rules to cryptocurrencies is not of great significance. Cryptocurrencies sold at low prices will inevitably recognize income and pay taxes when sold at high prices.

The following diagram shows the price trends of the top 10 cryptocurrencies by market capitalization on September 4, 2023. It can be observed that, except for stablecoins, the price trends of other cryptocurrencies are often similar, which means that the possibility for investors to evade taxes through wash trading is unlikely.

In conclusion, we believe that digital assets not being subject to IRC 1091 will not bring about serious tax issues.

5. Constructive Sales (IRC Section 1259)

a) Under what circumstances would a taxpayer consider the economic substance doctrine (IRC Section 7701(o)) applicable to constructive sales related to digital assets?

b) Are there best practices for constructive sales that are economically equivalent to transactions involving digital assets?

c) Should IRC Section 1259 be applicable to digital assets? Why?

d) Should IRC Section 1259 be applicable to assets other than digital assets? If so, which assets should it apply to? Why?

In response to this set of questions, we believe that IRC Section 1259 should not be applicable to digital assets. The reasons are similar to our answers to the previous set of questions.

Firstly, similar to the previous question, it is still difficult to determine the boundaries of “identical” or “substantially identical” digital assets. For example, in an NFT transaction, if an investor holds one NFT and sets up a bearish option against that type of NFT, the implementation of IRC Section 1259 would face difficulties as it is challenging to confirm whether the two transactions involve “identical” NFTs.

Similarly, the non-applicability of IRC Section 1259 to digital assets does not create significant tax issues. The cryptocurrency market is characterized by the rapid transition between bull and bear markets, with multiple transitions occurring within a short period. As a result, investors tend to hold cryptocurrencies for less “extremely long” periods. Therefore, the adoption of Constructive Sales rules for cryptocurrencies is not meaningful because the definitive time for the transactions will quickly arrive.

6. Timing and Source of Income from Mining and Staking

a) Please describe the various types of rewards provided by mining and staking.

b) How should the returns and rewards obtained from verification (mining, staking, etc.) be treated for tax purposes? Why? Should different verification mechanisms have different treatment methods? Why?

c) Should the nature and timing of income from mining and staking be the same? Why?

d) What are the most important factors in determining when an individual participates in the mining industry or mining activities?

e) What are the most important factors in determining when an individual participates in the staking industry or staking activities?

f) Please provide examples of arrangements for individuals participating in staking pool protocols.

g) Please describe the appropriate treatment for the various types of income and rewards obtained by individuals staking for others or staking in a pool.

h) What is the correct source of staking rewards? Why?

i) Please provide feedback on the proposal by the Biden administration to impose a consumption tax on mining.

(1) Mining Rewards and Staking Rewards

Mining rewards mainly include block rewards and transaction fees.

Block rewards: Block rewards refer to the newly issued digital assets that miners receive when a new block is generated. The quantity and rules of block rewards depend on different blockchain networks. For example, the block reward for Bitcoin halves every four years, from the initial 50 bitcoins to the current 6.25 bitcoins.

Transaction fees: Transaction fees are the fees paid by exchanges for each transaction included in a block, which are also allocated to miners. The quantity and rules of transaction fees also depend on different blockchain networks. For example, the transaction fee for Bitcoin is set by the sender and varies depending on the transaction size and network congestion.

Staking rewards refer to the process in which stakers support the consensus mechanism on the blockchain network and earn rewards. Basic rewards: Basic rewards are digital assets distributed to stakers based on the quantity and duration of their staking, according to a fixed or floating ratio.

Additional rewards: Additional rewards are digital assets distributed to stakers based on their performance and contributions on the network, such as block validation, voting decisions, and providing liquidity. The types and quantities of additional rewards depend on different blockchain networks, but generally can be divided into the following categories:

· Dividend rewards: Dividend rewards refer to a certain proportion of profits or revenue earned by stakers through participation in certain projects or platforms. For example, stakers can receive dividends from the transaction fees by participating in decentralized exchanges (DEX) on the Binance Smart Chain.

· Governance rewards: Governance rewards refer to governance tokens or other rewards issued to stakers through participation in the governance voting of certain projects or platforms. For example, stakers can receive ETH 2.0 issued by participating in Ethereum’s validation nodes.

· Liquidity rewards: Liquidity rewards refer to liquidity tokens or other rewards issued to stakers for providing liquidity for certain projects or platforms. For example, stakers can receive DOT issued by providing cross-chain asset conversion services (XCMP) on Polkadot.

The nature of rewards obtained from mining and staking is the same. Both mining and staking acquire corresponding token income through verification on the blockchain. The difference is that mining requires hardware equipment computing power, while staking requires virtual currency. However, they have the same on-chain verification mechanism. Therefore, the difference between mining and staking is only a difference in form. In our opinion, for entities, the income from mining and staking should be treated as operating income, while for individuals, it can be treated as investment income.

Due to the similar nature of mining and staking rewards, the time of recognizing income from both mining and staking should be the same. Income from mining and staking should be reported and taxed when the taxpayer obtains the right to control the rewarded digital assets. This typically refers to the point in time when the taxpayer is free to sell, exchange, use, or transfer the rewarded digital assets.

(2) Industry Activities

We believe that the question of “determining when an individual participates in mining/staking industry or mining/staking activities” is equivalent to determining whether a person is engaged in mining/staking as a business, which may subject them to self-employment taxes. Specifically, whether a person is engaged in mining/staking as a business can be assessed based on the following criteria:

Purpose and intent of mining: The individual engages in mining with the purpose of generating income or profit, and there is consistent and systematic mining activity.

Scale and frequency of mining: The individual uses a significant amount of computing resources and electricity, and engages in mining frequently or regularly.

Results and impact of mining: The individual obtains substantial income or profit through mining, and makes significant contributions or impacts on the blockchain network.

(3) Staking Pool Protocol

A staking pool protocol typically includes the following parts:

Creation and management of the staking pool: The staking pool protocol is usually created and managed by one or more pool operators who are responsible for running and maintaining staking nodes, as well as handling registration, deposits, withdrawals, and allocation of the staking pool. Pool operators typically charge a certain percentage of fees or commissions as their service compensation.

Participation and withdrawal from the staking pool: The staking pool protocol typically allows anyone to participate in or withdraw from the staking pool with any amount of digital assets, as long as they comply with the rules and requirements of the staking pool. Participants can join the staking pool by sending digital assets to the staking pool’s address or smart contract, and can also withdraw from the staking pool by requesting a withdrawal or redemption. Participants usually receive a token representing their share or stake in the staking pool, such as rETH, BETH, etc.

Earnings distribution of the staking pool: The staking pool protocol usually calculates and distributes the earnings of the staking pool periodically or in real-time based on the performance of the staking nodes and the reward mechanism of the network. Earnings typically include newly issued digital assets, transaction fees, dividends, governance tokens, etc. Earnings are usually distributed according to the participants’ share or stake in the staking pool, after deducting the fees or commissions of the operators, and are sent to the participants’ addresses or smart contracts.

(4) Response to Consumption Tax

The Biden administration’s proposal to impose a 30% consumption tax on the mining industry, we believe that this tax rate is too harsh during bear markets. The comprehensive earnings of the mining industry in bear markets and bull markets should be calculated, and a reasonable tax rate level should be separately determined. This tax rate level should not be excessively higher than cloud services or cloud computing businesses.

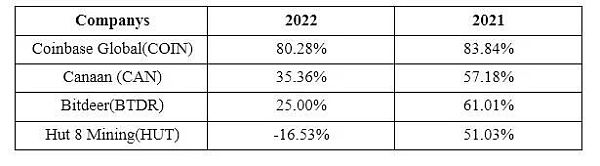

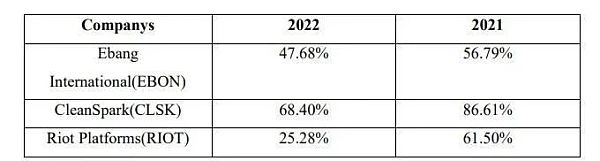

The table below shows the gross profit margin of major NASDAQ-listed companies in the mining industry during the bear market (2022) and bull market (2021). In 2022, the average gross profit margin was 37.92%, but in 2021, it was 65.42%. Because the consumption tax is different from the income tax, it is levied directly on mining income, which directly affects the company’s operating conditions. In the bear market, a 30% consumption tax is a significant blow to mining companies.

Another reason for imposing a consumption tax on the mining industry is that mining consumes a large amount of electricity, so it needs to be punished. However, we believe that mining industry’s use of electricity does not necessarily cause environmental pollution, as it may use clean energy. It is unfair to impose the same consumption tax on all mining companies. The government can regulate electricity prices to meet the environmental protection needs of mining enterprises.

7. Non-functional currency (IRC Section 988(e))

a) Should the micro-exception rule in IRC Section 988(e) be applied to digital assets? Why? What threshold is appropriate and why?

b) If the micro-exception rule applies, can the existing best practices prevent taxpayers from evading tax obligations? What reporting system helps taxpayers comply with the regulations?

The micro-exception rule in IRC Section 988(e) should be applied to digital assets. Similar to securities investments, digital asset transactions typically involve foreign exchange, so if each digital asset transaction requires verification of foreign exchange losses, it would create a great administrative burden. We believe that the threshold specified in IRC Section 988(e) is appropriate.

Applying the micro-exception rule to digital assets may lead to taxpayers evading tax obligations. In this regard, we recommend referring to relevant national tax laws and voluntarily reporting each transaction without verifying foreign exchange losses. However, at the end of the tax year, a random sample of transactions should be checked to verify whether foreign exchange losses have been reported truthfully. If a trader fails to report foreign exchange losses truthfully, they will face corresponding penalties. This system design will help taxpayers comply with tax reporting requirements.

8. FATCA and FBAR Reporting (IRC Sections 6038D, 1471-1474, 6050I, and 31 U.S.C. Section 5311 et seq.)

a) When should taxpayers report digital assets or digital asset transactions on FATCA forms (e.g., Form 8938), FBAR FinCEN Form 114, and/or Form 8300? If taxpayers report certain categories but not others, please explain and specify the reported and unreported categories of digital assets on these forms.

b) Should the reporting requirements of FATCA, FBAR, and/or Form 8300 be clarified to eliminate ambiguity regarding whether they apply to all or certain categories of digital assets? Why?

c) In view of the policies behind FBAR and FATCA, should digital assets be further included in these reporting systems? Are there any obstacles to doing so? What kind of obstacles?

d) When determining compliance with the requirements of FATCA, FBAR, and Form 8300, how should stakeholders consider wallet custody? Please provide examples of wallet custody arrangements and indicate which types of arrangements should or should not comply with the reporting requirements of FATCA, FBAR, and/or Form 8300.

(1) Response to reporting rules

Generally speaking, we recommend designing a new form for reporting all digital assets. This would contribute to the development of the digital asset industry, as reporting digital assets in the current forms may be cumbersome and could hinder trading activity.

However, if reporting needs to be done within the existing forms, we suggest the following reporting methods:

For FATCA forms (such as Form 8938), taxpayers should report any form of digital assets held or controlled abroad, regardless of whether they are associated with US dollars or other fiat currencies. This includes but is not limited to cryptocurrencies, stablecoins, tokenized assets, non-fungible tokens (NFTs), decentralized finance (DeFi) protocols, etc. Taxpayers should convert their foreign digital assets to US dollars based on year-end exchange rates and determine whether they need to file Form 8938 based on the reporting thresholds.

For FBAR FinCEN Form 114, taxpayers should report overseas custody or non-custodial digital asset wallets that can be considered as financial accounts if the total value of these accounts exceeds $10,000 at any time. Taxpayers should convert their foreign digital assets to US dollars based on year-end exchange rates and provide relevant account information on Form 114.

For Form 8300, taxpayers should report cash or cash equivalents received from the same buyer or agent that exceeds $10,000, including cryptocurrencies. Taxpayers should convert the received cryptocurrencies to US dollars based on the exchange rate on the day of the transaction and provide relevant transaction information on Form 8300.

(2) Response to wallet custody

Regarding wallet custody, our views are as follows:

A cryptocurrency wallet is a tool used to store and manage digital assets, and it can be categorized into custodial wallets and non-custodial wallets. The following are the definitions and differences between these two types of wallets:

A custodial wallet refers to entrusting the cryptographic keys to a third-party service provider, such as an exchange, bank, or professional digital asset custodian, who is responsible for storage and management.

A non-custodial wallet refers to controlling one’s own cryptographic keys, such as using software wallets, hardware wallets, or paper wallets.

We believe that regardless of the type of wallet used, taxpayers should report their holdings of digital assets in Form 8938 or Form 8300 in accordance with current regulations. However, in order for taxpayers to report digital assets in FBAR FinCEN Form 114, it is necessary to clarify whether a cryptocurrency wallet constitutes an overseas financial account. We believe that custodial wallets provided by overseas service providers can be considered as overseas financial accounts; further discussion is needed for non-custodial wallets.

On the one hand, some non-custodial wallets may not be considered as foreign financial accounts because they do not involve the participation or control of third parties. For example, if a hardware wallet or paper wallet is used, and the user has complete control over their private keys and digital assets, the user may not need to report these wallets on the FBAR form because they are personal property, not foreign financial accounts.

On the other hand, some non-custodial wallets may be considered as foreign financial accounts because they involve the services or functions of third parties. For example, if a software wallet is used and the wallet can connect to a foreign exchange or platform, or provides cross-border transfer or exchange functions, they can be considered as foreign financial accounts.

However, whether it is a custodial or non-custodial wallet, as long as the wallet is associated with a foreign financial account, for example, if cross-border transfers or exchanges are conducted through the wallet, it may be necessary to report the wallet on the FBAR form because it involves a foreign financial account.

9. Valuation and substantiation (IRC Section 170)

a) Digital assets currently do not meet the exception provisions of IRC Section 170(f)(11) for assets with readily obtainable fair market value. Should the substantiation rules be modified to consider digital assets? If so, in what manner and for which types of digital assets? Specifically, should different measures be taken for publicly traded digital assets?

b) What characteristics should exchanges and digital assets have in order to appropriately apply this exception, and why?

We believe that the relevant provisions of IRC Section 170 should be amended to include donations of digital assets. However, the digital assets that can be deducted for tax purposes should be limited to common, publicly traded digital assets, not all digital assets. Digital assets such as NFTs that are difficult to obtain fair market value should not be subject to the exception provisions of IRC Section 170(f)(11) because their transactions can be artificially controlled. Moreover, it is more difficult to monetize digital assets such as NFTs with limited fair value, which would increase additional costs for the recipients of donations. Policy should encourage donors to donate easily monetizable cryptocurrencies.

Specifically, we believe that digital asset donations with readily obtainable fair market value, as determined in accordance with Notice 2014-21 and related documents, can be subject to the exception provisions of IRC Section 170(f)(11), such as virtual currencies that are “traded on at least one platform with real currency or other virtual currency and have a published price index or value data source”.

We will continue to update Blocking; if you have any questions or suggestions, please contact us!

Was this article helpful?

93 out of 132 found this helpful

Related articles

- Focus on the metaverse and generative AI, four departments issue the Implementation Plan for the New Industry Standardization Pilot Project.

- Digital Asset Anti-Money Laundering Bill Faces Obstacles in the U.S. Senate

- An in-depth analysis of Hong Kong’s Web3 policies since the release of the ‘Declaration

- Five key points to watch in Hong Kong’s cryptocurrency policy in the next year after opening up retail trading

- Hong Kong Treasury Bureau’s Chen Haolian The development of Web3.0 should not undermine the stability of the financial system.

- Recent Amendments to Cryptocurrency-related Legislation in the US Congress

- All you need to know | China AIGC Entrepreneurship Legal regulation and policy summary (July 2023)