The collective behavior of governance on the chain: how is power distributed? Why do we need chain governance?

Proponents of chain governance praise the effective decision-making and rapid execution of this model. Opponents of the model on the chain believe that it deprives the node operator of the rights, thereby eliminating the discriminating power required to perform branch protocol updates. Supporters responded by saying:

“Stakeholders have a very clear and broad motivation to do things that are good for the network”

“Stakeholder incentives increase the value of existing token holdings, which makes them responsible for doing what they can to the platform”

Who are the stakeholders?

- QKL123 market analysis | Ethereum is already on the road, when will Bitcoin start again? (0923)

- Forget about NVT and currency exchange equations, this has a new model for crypto asset valuation.

- Is traditional bank and DeFi isolated from each other? No, Linen allows non-encrypted users to borrow on encrypted assets.

Although stakeholders include countless different interest groups in the blockchain, they can be broadly divided into four categories: developers, miners, users, and token holders.

Developers are people who write software that allows nodes to communicate with each other. There can be multiple independent teams working on different implementations of the software. They benefit from:

1. Social recognition;

2. Establish the legality of the future development direction of the software;

3. Increase the value of existing tokens.

The node operator (or miner) is the person running the full node. They bundle transactions with transaction costs as part of a production mix. Their main income stems from the success and efficiency of the blockchain. They benefit from:

1. Expected future block rewards;

2. Estimated future transaction costs;

3. Increase the value of existing tokens.

Users are the people who gain a performance experience in a distributed application platform. They trade and exchange goods and services on the platform. Their interests depend on their use of the platform itself. They benefit from:

1. New features;

2. Faster transaction speed;

3. Affect the value of existing token holdings.

Token holders are people who have a large number of tokens on the blockchain. They sell the tokens to the user, who then uses the tokens to purchase goods and services on the platform. In the Proof-of-Stake (PoS) system, token holders can also purchase tokens as a value store (I will explain why this is important later). They benefit from:

1. Equity weighted voting system;

2. Increase their interest in the blockchain;

3. Increase the value of existing tokens.

So this is the problem. Indeed, all of the stakeholders defined above benefit from the value of the existing token holdings. But for each group, the value of affecting tokens is only one-third of the overall incentives of all of their networks. This means erroneously assuming that all stakeholders want to increase the value of the token implies: 1) this is their highest priority in the entire network; 2) the stakeholder must be in the value of the token or other benefits In the case of a choice between the two, the value of the token is always the most important.

The result of this flawed logic is that this assumption is made about the sole purpose of the stakeholder being the token value. To sum up, this paradox means:

A person using a blockchain network is considered a stakeholder if and only if its sole priority is to increase the value held by the existing token.

Allocation of power in chain governance

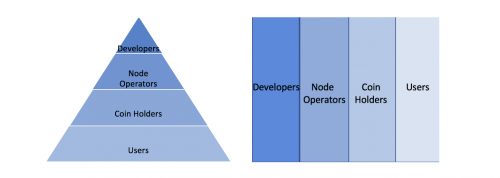

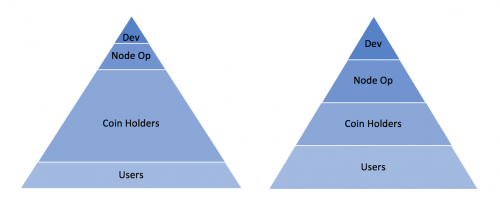

Ideally, the population distribution of the four interest groups is similar to the pyramid. Developers are the smallest interest groups, followed by node operators, and so on. But in the chain of governance, each interest group has the same power.

In the chain governance, the equal distribution of power in the model makes the opposite relationship between the different interests and incentive modes of each group. When each group receives equal power distribution, it ensures that one group is not dominated by another. Maintaining a balance of power between different interests allows everyone to enjoy decision-making power.

Population Distribution and Distribution of Power in Chain Governance

In an equally distributed system, the token holder has the same influence on the direction of the network as other people compared to other groups. However, in the equity weighting system, power is tilted toward the token holder; some oligopoly appears in the token holder, and most of the wealth is held by a small number of participants. For example, 1.6% of EOS holders own 90% of tokens. If the voting system is based on equity, then only 1.6% of the participants can do whatever they want.

In this way, chain governance restores the pyramid structure to a power distribution system. While some people may be both token holders and users, or even if most users are token holders, the chain model involved in equity-weighted voting does not fairly bias power toward token holders. Even in networks with equal wealth distribution, the system empowers users and largely deprives node operators and developers of the key role in the blockchain environment.

Unbalanced Wealth Transmission and Balanced Wealth Transfer in the Distribution of Power in Governance

Why the blockchain community should pay attention to this

Suppose an entity on the chain is illegally invaded and steals $40 million from a smart contract. There is a proposal in front of it that can create an unconventional transition state, so that the stolen token can be returned to the original owner. Unfortunately, the oligarchs in current token holders have more power than those who want to return stolen tokens. Therefore, these oligarchs will not vote to return stolen tokens and release their powerful power in the blockchain. Most users with a minority interest will not be able to recover lost tokens, while "coin whales" will continue to hold a majority interest. The result will be that users who are deprived of their rights may choose to abandon the network.

Continue to follow this example and imagine that another $40 million was stolen by a developer-invested smart contract that was hacked. In this case, there is no token whale in this space. There is also a proposal in front of it to create an unconventional transition state, so that the stolen token can be returned to the original owner. However, it is still unfortunate that in this case, developers will not hold a large number of interests to vote for this proposal, and most users have no incentive to vote for this proposal because their own tokens have not been Pirates.

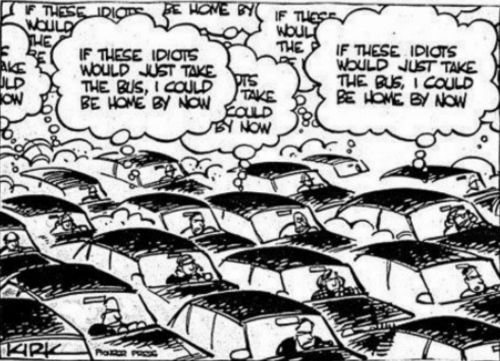

This is the main paradox in the dispute over chain governance. It fails to recognize these inherent problems between stakeholders. In politics, we call this a collective behavior problem. In this case, even if the alternative is more beneficial to the entire group as a whole, the individual will still make the choice that best suits his or her own interests. Compared with everyone's cooperation in supporting the public interest, if everyone only maintains one's own self-interest, the result will usually be worse.

Now, if this proposal is proposed in the under-chain model, the token whale, even if it exists, cannot control the direction of the governance model. After the hacking, most users will propose to change the direction of the chain, the whole process will be more democratic. In the second example, the developer will exercise power over the user as an equal stakeholder, rather than voting on the proposal as a minority stakeholder in the chain vote. No group would think it necessary to circumvent the formal legislative process because every voice needs to be heard fairly.

Why do you want to carry out chain management?

Once any single proposal meets the voting threshold, the chain governance is automatically updated. This necessarily means that the ability of the node operator to decide whether to install this update has been weakened. If wealth is not evenly distributed, and these token whales dominate cyberspace, this necessarily means that the power of users and node operators is deprived.

As mentioned earlier, the node operator consciously decides whether to set up a hard fork to provide the balance of power needed to create an antagonistic relationship between different interest groups. If node operators and users follow the chain process, they will naturally be deprived of their rights, but more importantly, they are increasingly reluctant to reject hard fork updates. Most importantly, Vlad Zamfir pointed out that voting on the chain does not resist Sybil-resistant. By expanding, any full-node participant will be deprived of the opportunity to participate moderately in a model that has long been unfavourable to them.

In the chain of governance: it is also true. It is indeed possible for one group to rule another. There is indeed a problem of collective action. Wealth may indeed be unevenly distributed. The difference is that 50% +1 under the chain does not constitute a revolution that takes place on the chain.

Under the chain, developers can express hope for the direction of the platform, and at least in the early stages of the blockchain platform, usually play an important role in the development of protocol hard fork updates. Node operators are able to discuss and express their concerns about the update, and ultimately make the final decision by choosing to update or not to update the agreement. Users and token holders can vote and make conscious decisions to continue to participate and invest in the platform.

Their faction identity is independent of each other. The expectation of the platform is a two-way road: developers, node operators, users, and token holders expect different things outside the blockchain, and the platform as an organism also expects to be different from each other. This social hierarchy provides an ecosystem that can thrive.

These are human problems, not blockchain issues or cryptocurrencies. Both governance models can be attributed to these types of collective behavior problems. The difference is that under-chain governance provides more flexibility in adapting and making changes than chain-based models to eliminate collective behavior problems.

in conclusion

At this point, it is clear that on many potential management issues, the incentives between developers, miners, users, and token holders are perpendicular to each other. Therefore, as a benefit group, these four sub-groups will provide conflicting solutions to every problem faced by stakeholders.

Zamfir issued a stern statement on this topic:

Participants' information and motivation limit their participation, so they need to understand in the underlying cultural background and in their personal context. The information and motivation of the participants can change over time, but these things do not change immediately, nor do they change independently of each other's motivations and state of knowledge. The process of changing the way things are governed is not magic. In our opinion, this is also a human choice.

A successful governance model will be versatile enough to change and adjust over time. All charters should be considered as dynamic documents with growth capabilities. In the blockchain, the result is an imperfect system. However, it balances the entire platform by allowing opposing relationships between each faction, which makes the dictatorship of the minority almost impossible. Governance in the chain is not democracy, but tyranny.

The Collective Action Problem of On-Chain Governance

This article is compiled from Medium in the financial network chain and does not represent the financial position of the financial network.

Author: Mallika Parlikar

Original link: https://medium.com/@parlikarmallika/the-collective-action-problem-of-on-chain-governance-faf560106ac5

We will continue to update Blocking; if you have any questions or suggestions, please contact us!

Was this article helpful?

93 out of 132 found this helpful

Related articles

- Zhu Min: Libra may bring 4 kinds of subversion, 7 opportunities

- Starting to sell 8 bitcoins in 2 hours, is Bakkt’s bull market myth gone?

- Bakkt officially launched, taking stock of the advantages of Bakkt, why is the bull market still not coming?

- Bakkt is officially open for trading, there are 5 things you don't know.

- Dutch oil and gas giant Dietmann uses blockchain platform to simplify the deployment of projects on the chain

- Funds Fair Win and imitation led to the congestion of Ethereum in the past few days, and the number of confirmed transactions was as high as 120,000.

- Demystifying the airdrop ecology of “nothing to be born”: Some people bought a house, and some people got nothing.