G7 Stabilization Coin Report (full text): Stabilizing coins may be more capable of acting as a means of payment and value storage

Author: The number of chain team rating

Source: Number Chain Rating ShulianRatings

Editor's Note: The original title is "G7: Stabilizing coins may be more capable of acting as a means of payment and value storage."

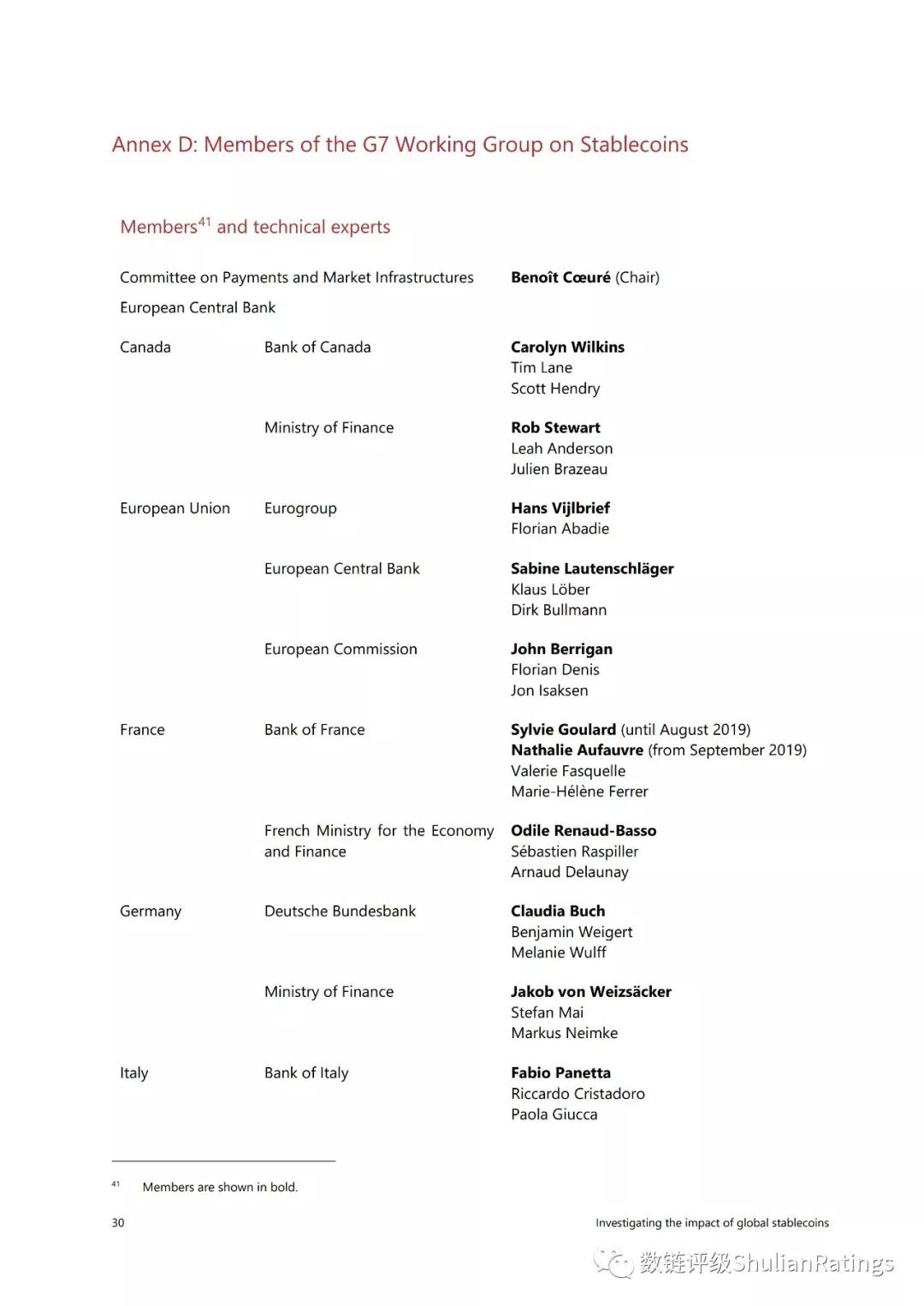

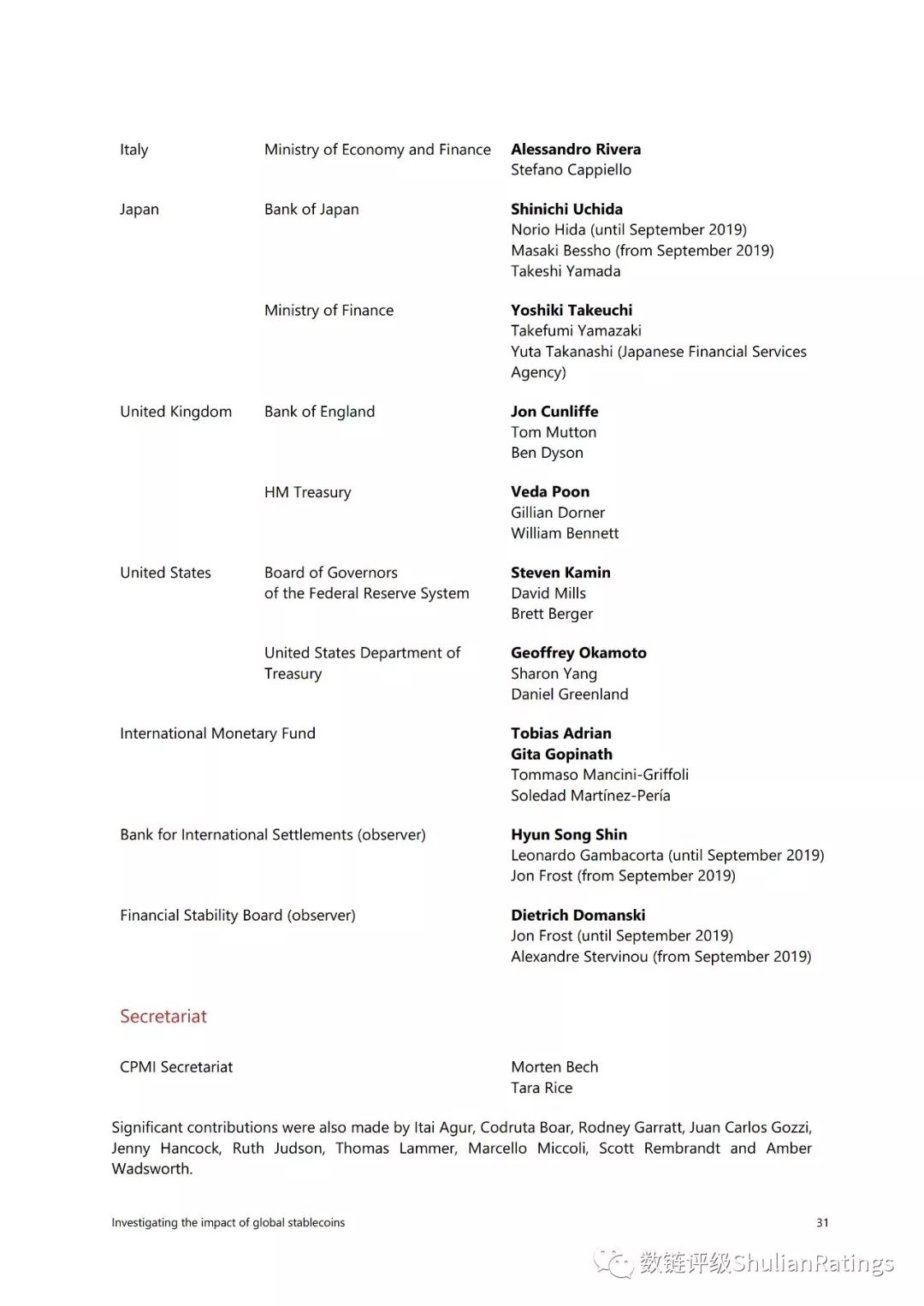

The Stabilization Coin Working Group, composed of the Group of Seven (G7) France, the United States, Japan, Canada, Italy, Germany and the United Kingdom, issued a final report on the stabilization of the currency on Thursday.

- Dai meets the biggest opponent? Tether considers developing algorithm stabilization currency USDTX

- Lawyer's point of view | Xiao Wei: The policy and regulatory risk of the stable currency comes from two aspects.

- The stability of the certification is afraid of being regulated, will Tether give up the USDT?

We believe that the international regulation of the digital asset industry is guided by the G7 and G20 and dominated by the United States . According to the G7 report, more and more countries offer domestic payment systems that offer cheap and near-instantaneous. However, current payment services still present challenges. Most importantly, cross-border payments are still slow, expensive and opaque, especially for retail payments (such as remittances). Globally, despite the fact that 1.1 billion adults own mobile phones, there are still 1.7 billion adults who cannot use trading accounts.

Given the innovative potential of the underlying technology, cryptographic assets were originally conceived to address some of these challenges. However, to date, they have suffered many restrictions, not only serious price fluctuations. As a result, for some investors and investors engaged in illegal activities, encrypted assets have become highly speculative asset classes rather than a means of payment.

Stabilized coins have many of the characteristics of encrypted assets, but attempt to stabilize the price of the "coin" by linking their value to the value of the pool of assets. As a result, stable currencies may be more capable of acting as a means of payment and value storage, and they may make a faster, cheaper, and more inclusive contribution to the development of a global payment system than existing systems. That is to say, Stabilizing coins is just one of many initiatives to try to solve the existing challenges in the payment system, and as an emerging technology, they are largely untested.

The G7 finance minister and central bank governor requested a report from the Stabilization Coordination Working Group, including its recommendations, before the October 12th International Monetary Fund Annual Meeting. The report reflects the discussion of the Stabilization Currency Working Group.

In addition, today, the People's Bank of China issued a document saying that on October 17-18, 2019, the central bank governor Yi Gang and deputy governor Chen Yulu attended the G20 fiscal and central bank ministerial level in Washington, DC. Deputy level meeting. The meeting unanimously agreed to issue the G20 statement on stable currency, affirming the potential benefits of financial innovation, and pointed out that stable currency has a series of policy and regulatory risks, especially in the areas of anti-money laundering, counter-terrorism financing, consumer protection, market integrity, etc. Evaluate and address these risks before the Stabilization Coin project begins . The meeting requested international institutions such as the Financial Stability Board, the IMF, and the Financial Action Task Force to continue to study the risks and impacts of the stable currency.

The following is the report of the G7 Stabilizing Coin Working Group.

Investigating the Impact of Global Stabilization Coins & the G7 Stabilization Coin Working Group

October 2019

Summary

Technological innovation is changing the delivery of financial services and products. Especially in recent years, significant changes have taken place in payment services by introducing new payment methods, platforms and interfaces. In fact, more and more countries offer domestic payment systems that offer cheap and near-instantaneous. However, current payment services still present challenges. Most importantly, cross-border payments are still slow, expensive and opaque, especially for retail payments (such as remittances). In addition, there are 1.7 billion financial services worldwide that lack banking services or underserved services.

Given the innovative potential of the underlying technology, cryptographic assets were originally conceived to address some of these challenges. However, to date, they have suffered many restrictions, not only serious price fluctuations. As a result, for some investors and investors engaged in illegal activities, encrypted assets have become highly speculative asset classes rather than a means of payment.

Stabilized coins have many of the characteristics of encrypted assets, but attempt to stabilize the price of the "coin" by linking their value to the value of the pool of assets. As a result, stable currencies may be more useful as a means of payment and value storage, and they may make a faster, cheaper, and more inclusive contribution to the development of a global payment system than existing systems. That is to say, Stabilizing coins is just one of many initiatives to try to solve the existing challenges in the payment system, and as an emerging technology, they are largely untested.

However, these potential benefits can only be realized if significant risks are addressed. Stabilizing coins, regardless of size, will bring the following legal, regulatory and supervisory challenges and risks:

-

Legal certainty -

Sound governance, including investment rules for stability mechanisms -

Money laundering, terrorist financing and other forms of illegal financing -

Payment system security, efficiency and integrity -

Network security and operational flexibility -

Market integrity -

Data privacy, protection and portability -

Consumer/investor protection -

Tax compliance In addition, achieving stable coins on a global scale can pose challenges and risks to: -

Monetary Policy -

Financial stability -

International monetary system -

fair competition

Private sector entities that design a fixed currency system are expected to address various legal, regulatory and supervisory challenges and risks. In particular, such systems will need to comply with the necessary standards and requirements and comply with the relevant laws and regulations of the various jurisdictions in which they operate. They also need to combine sound governance and appropriate end-to-end risk management practices to address them before they occur. The Group of Seven (G7) believes that until the above-mentioned laws, regulations and regulatory challenges and risks are adequately addressed, through proper design, and through adherence to regulation that is clear and proportional to the risks, global stable currency projects should not Start the operation. That is, depending on the unique design and details of each stable currency system, approval may depend on other regulatory requirements and adherence to core public policy objectives.

If used in a global nature, certain risks are amplified and new risks may arise. Stabilizing currency programs built on existing (large and/or cross-border) customer segments may have the potential to expand rapidly to achieve global or other substantial coverage. These are known as the Global Stablecoins (GSCs).

GSCs may have a significant adverse impact on the transmission of monetary policy and financial stability at home and internationally, in addition to combating money laundering and terrorist financing across jurisdictions. They may also have a broader impact on the international monetary system, including currency substitution, and therefore may pose a challenge to monetary sovereignty. The GSCs also raised concerns about fair competition and antitrust policies, including those related to payment data. These systematic risks deserve careful monitoring and further research. The interests and risks of both parties in the GSCs may be more significant affecting some countries, depending on the country's development of their existing financial and payment systems, their currency stability and their level of financial inclusion, among other factors.

For stable currency developers, there is a sound legal basis in all relevant jurisdictions, especially the legal clarity of the claims nature of all participants in the stable currency ecosystem (eg token holders and issuers), It is an absolute premise. Your rights and obligations can make the stable currency system vulnerable to lost confidence – an unacceptable risk, especially in a potentially globally important payment system. Whether the value is stable depends on market mechanisms, such as the presence of an active network of distributors, or a commitment by the issuer at a given price, it should be proven that this system will be available at all times and all customers Achieve their goals. Arrangements in the governance structure are good investment rules, and the stability mechanisms must also be fully specified and understood by the participants.

Public agencies must coordinate across agencies, departments, and jurisdictions to support responsible payment innovation while ensuring consistent risk mitigation on a global scale. To this end, a number of international organizations and standards-setting bodies have issued guidance, principles and regulatory standards and existing payment arrangements, including cryptographic assets, which cover many of the challenges listed above. These include the Financial Market Infrastructure (PFMI) principles for systemically important payment arrangements, including the Financial and Market Infrastructure Committee (CPMI) and the International Securities Commission (IOSCO), and the recently strengthened Financial Action Task Force ( FATF) Recommendations: AML/CFT and the financing of the proliferation of weapons of mass destruction (which includes standards involving virtual assets and virtual asset service providers). Capital markets and banking regulations and standards may also apply to all aspects of stable currency arrangements. International organizations and standards-setting bodies should continue to assess the applicability of their existing frameworks to address any new issues and challenges that Stabilization Coin may bring.

In addition, the competent authorities in each jurisdiction should comply with these principles and standards and apply them to the stable currency system. Public institutions should adopt technology-neutral, function-based regulatory approaches and should take care to prevent harmful regulatory arbitrage and ensure a level playing field.

Stabilizing coins can combine new and untested technologies with newly entered financial services, and the resulting risks are outside the existing framework. This may also create new risks by requiring compliance with the highest regulatory standards, possibly modifying existing standards or creating new ones, and addressing them after a comprehensive assessment of local regulations and potential regulatory loopholes. The Financial Stability Board (FSB) and standards-setting bodies are stepping up their efforts to assess how their existing principles and standards can be applied to stable currencies and/or develop new policy recommendations to stabilize the currency in a globally consistent and coordinated manner. . In this regard, the G7 Working Group welcomes the FSB's plan to conduct an assessment, collaborate with standard-setting bodies, on key management issues surrounding the global stabilization currency, and submit an advisory report to the G20 Finance Minister and the central bank in April 2020. Long, the final report will be released in July 2020.

Finally, it should be emphasized that the emergence of innovation in the payment system by the private sector does not mean that public authorities will stop trying to improve the current system. The Ministry of Finance, central banks, and standards-setting bodies, such as CPMI and relevant international organizations, should continue their efforts to promote faster, more reliable and less costly payment systems for domestic and cross-border purposes, where appropriate, with new processes, And in a globally consistent and coordinated manner. In the special public sector, efforts should be redoubled to support measures to improve financial inclusion.

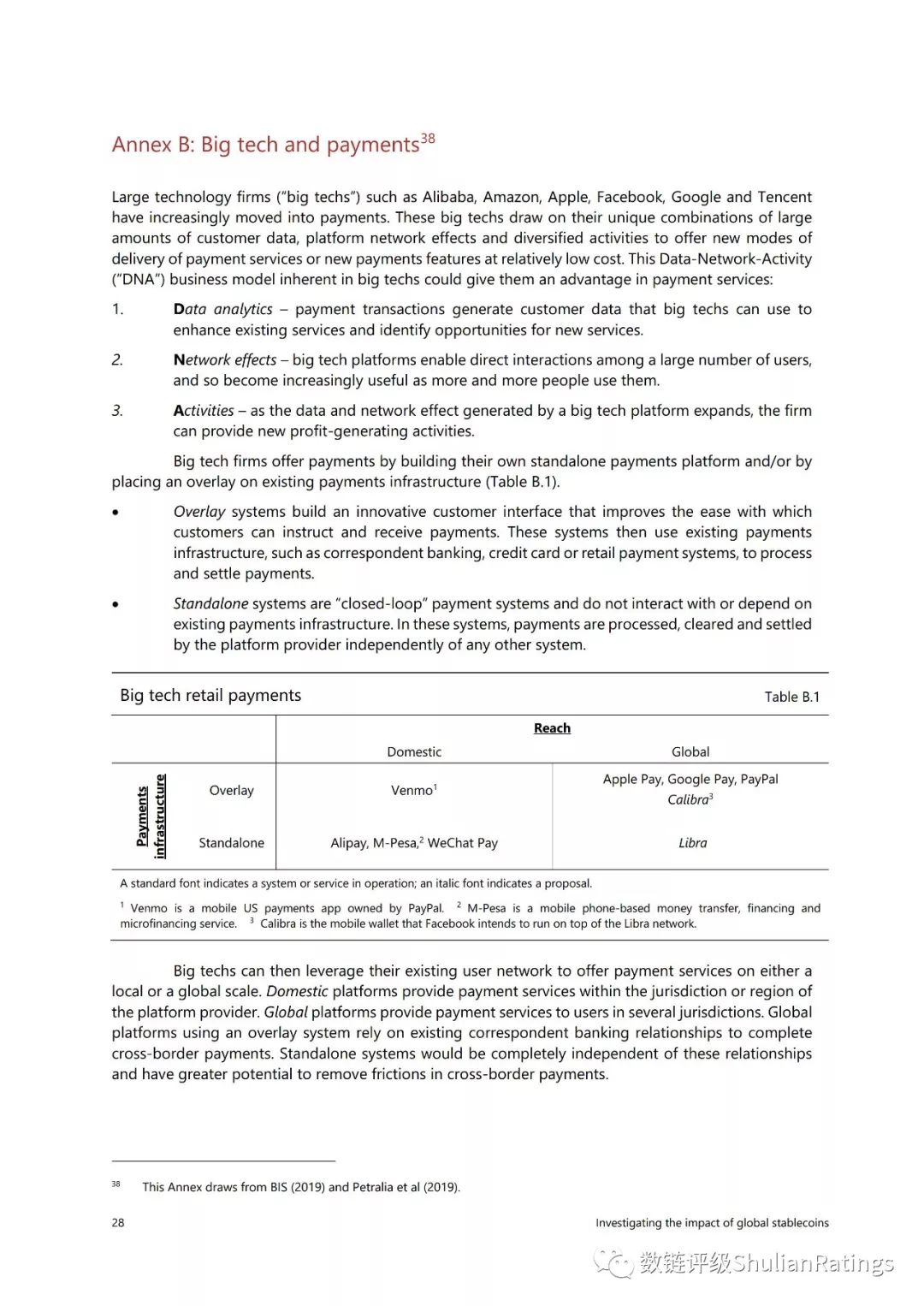

We encourage central banks, financial authorities, standards-setting bodies, etc. to use the CPMI and relevant international organizations to develop roadmaps for improved efficiency and cost-reducing payments and financial services. The initial recommendation was the report in the overview. In addition, the Central Bank will continue to share knowledge and experience on various possible solutions to improve payment systems. Finally, the central bank, individual and collective, will assess the relevance of issuing central bank currency figures (CBDCs) that take into account costs and benefits within their respective jurisdictions.

1, Introduction

Payments are in a state of constant change and innovation is widespread. In most cases, domestic payments are more and more convenient, and they can be used 24/7 in real time. The traditional bank-led ecosystem was disrupted, from the following startups, and from above to the establishment of large technology stocks. In a recent survey, when asked about which financial products and services were most affected by technological developments and competition, banks and technology companies would pay the highest whether they are now or in the next five years (Petralia et al (2019)).

Despite significant improvements in recent years, current payment systems still have two major drawbacks: a lack of universal access to financial services and a large share of the world's population and inefficient cross-border retail payments. Globally, despite the fact that 1.1 billion adults own mobile phones, there are still 1.7 billion adults who cannot use trading accounts (Demirgüç-Kunt et al. (2018)). Since trading accounts are the gateway to other financial services such as credit, savings and insurance, the inability to access such accounts hinders financial inclusion (Curére (2019a)).

To date, the first wave of cryptographic assets (best known as Bitcoin) has failed to provide reliable and attractive ways to store payment or value. They suffer from large price fluctuations, scalability limitations, complex user interfaces, and governance and regulatory issues as well as other challenges. Therefore, for some investors and investors engaged in illegal activities, crypto assets are more of a highly speculative asset class, rather than as a means of payment.

Currently, emerging stable currencies have many of the characteristics of more traditional cryptographic assets, but try to stabilize the price of the “coin” by linking its value to the value of the asset or pool of assets. The term "stable currency" does not have an established international classification, and such currency may not actually be stable and may present similar risks to other cryptographic assets. This report focuses on stable currencies that are claimed on behalf of a particular issuer or underlying asset or fund or other right or interest.

These stable currencies may be easier to use as a means of payment and value storage and may facilitate the development of a global payment system that is faster, cheaper and more inclusive than current arrangements. As a result, they may be able to address some of the shortcomings of existing payment systems and bring greater benefits to users.

Stabilizing coins can be used by anyone, or only by a group of participants, ie financial institutions or financial institutions that choose customers. The report covers issues that apply to all stable currencies and sometimes raises issues that are particularly relevant to retail stable currencies.

A stable currency system is part of an ecosystem that includes multiple interdependent entities with different roles, technologies, and governance structures. Appropriate regulation and accountability need to understand how the entire ecosystem and its components interact. The stable currency system is expected to meet the same standards and comply with the same requirements, as the traditional payment, clearing and settlement system – that is, the same activities, the same risks should face the same regulations. Therefore, stable coin developers should work to ensure that the stable currency ecosystem is designed to comply with public policy and operate safely and efficiently.

Stabilizing coins as public policy, monitoring and regulations bring many potential challenges and risks, including legal certainty, sound governance, anti-money laundering and counter-terrorism financing (AML / CFT), operational flexibility (including cybersecurity), consumers /Investor and data protection, and tax compliance. These risks can be partially addressed within the existing regulatory, supervisory and supervisory framework, but there may also be regulatory gaps. As long as the regulatory and policy framework does not conflict with public policy objectives, including monetary sovereignty, it is expected to remain technologically neutral and will not hinder innovation.

Recently, there have been many stable currency programs, some of which are sponsored by large technology or financial companies. With a large existing customer base (possibly cross-border), these new stable currencies are likely to expand rapidly to achieve global or other substantial footprints. These are known as the Global Stability Coin (GSC).

Because of their size and impact, the GSC may also pose challenges to fair competition, financial stability, monetary policy, and the extreme international monetary system (Curée (2019c)). They can also affect the security and efficiency of the entire payment system. Part of these challenges stem from the fact that GSC may move from a cross-border payment solution to an asset with similar currency functions.

At a meeting held in Chantilly in July 2019, the G7 finance ministers and central bank governors agreed that stable currencies – especially those with global and potential system footprints – caused serious regulatory and systemic problems. In addition, the Minister and the President agreed that the Stabilization Coin Initiative and its operators must meet the highest standards and be subject to prudential supervision and supervision, and that possible regulatory gaps should be assessed and addressed as a matter of priority. The G7 finance ministers and central bank governors requested a report to the Stabilization Coordination Working Group, including its recommendations, before the International Monetary Fund World Bank Annual Meeting in October 2019, which reflected the discussions of the Working Group.

The Group of Seven believes that the Global Stabilizationcoin program should not be operational unless it is adequately designed and adhered to with clear and proportional regulations to adequately address the above legal, regulatory and supervisory challenges and risks. That is, depending on the unique design and details of each stable currency arrangement, approval may depend on other regulatory requirements and adherence to core public policy objectives.

The report was organized as follows. The first provides an overview of the need to stabilize the ecosystem of coins to improve payment systems and services. Section 2 details the regulatory, supervisory, and policy issues associated with the Stabilization Coin Program and highlights the specific challenges inherent in the GSC. Section 3 provides an initial review of the existing regulatory and supervisory system that can be applied to stable currencies. Section 4 lists the way forward, including improving cross-border payments.

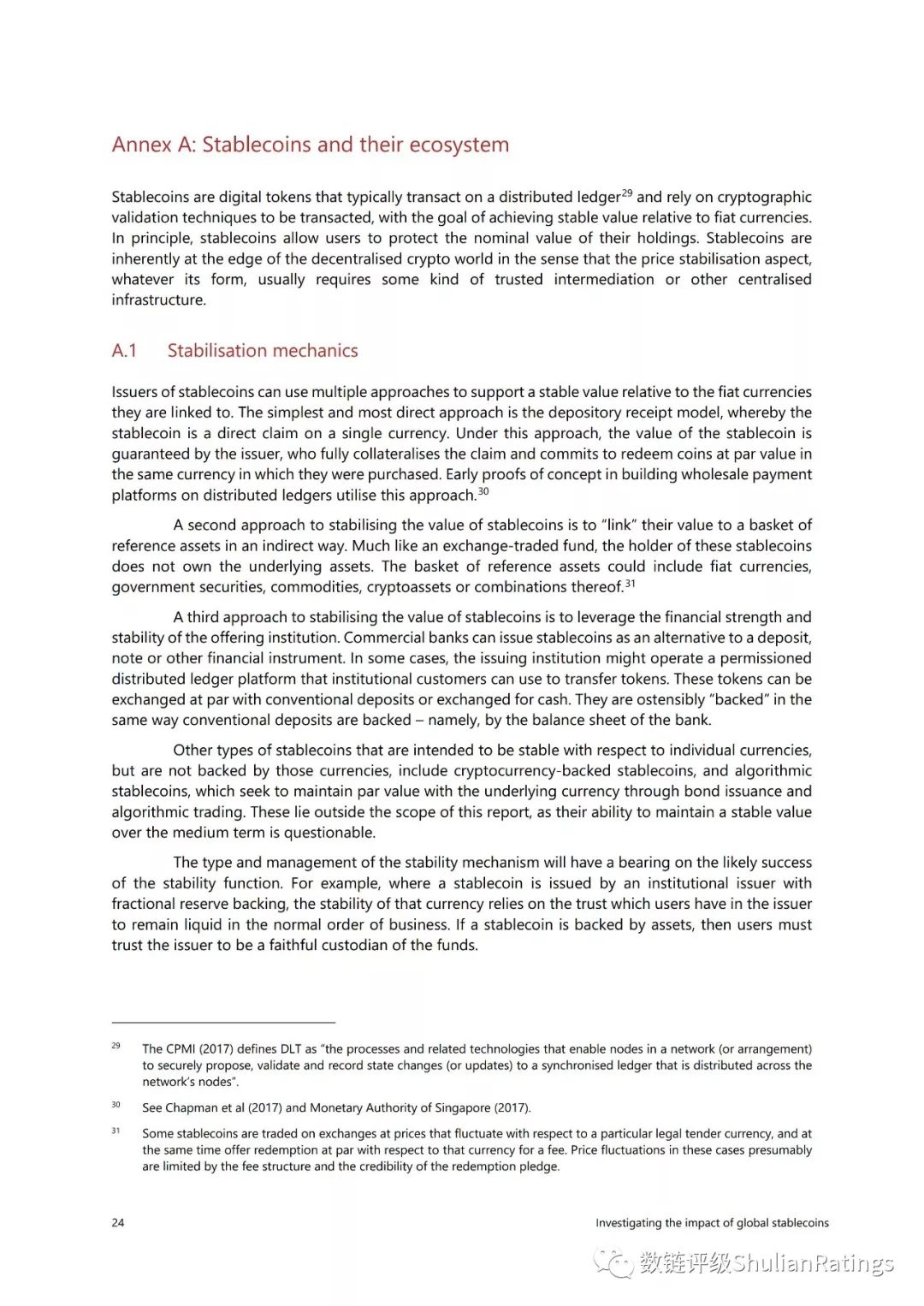

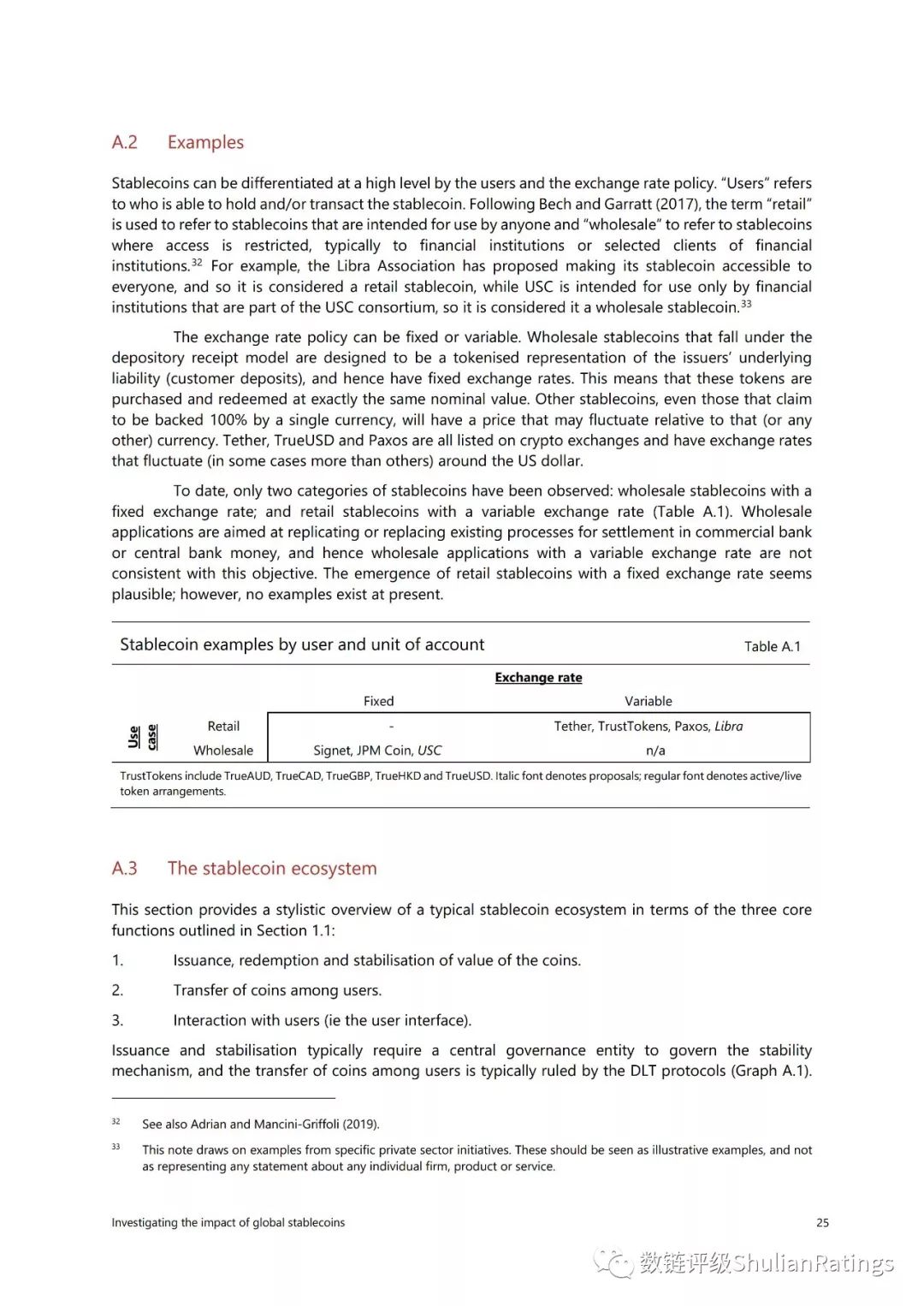

1.1 Stabilizing the currency ecosystem

-

The arrangement of stable currencies is a complex ecosystem that may vary significantly depending on its design.

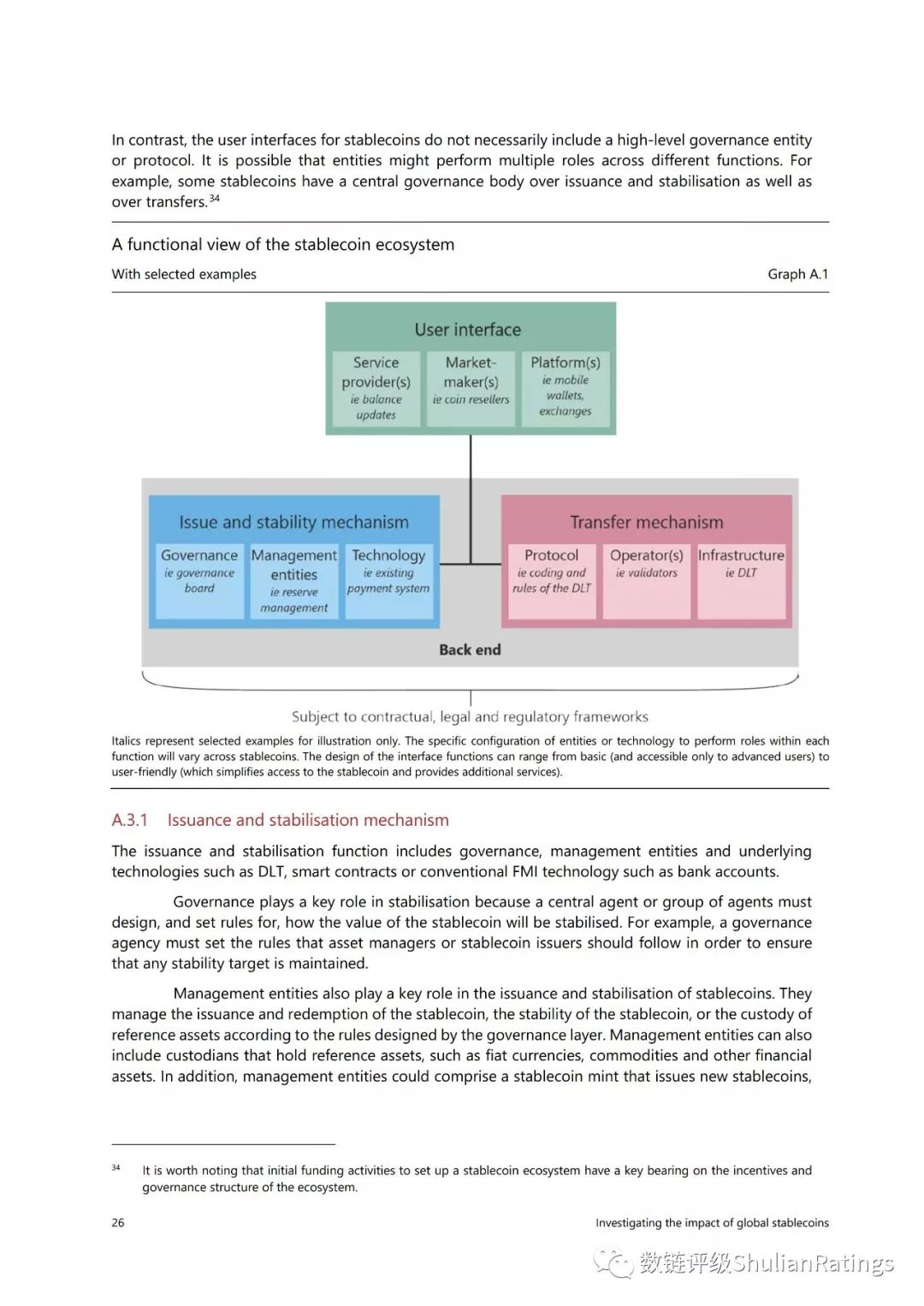

Stabilizing coins usually function in a wider ecosystem and provide the following core functions:

(a) The value of issuing, redeeming and stabilizing coins.

(b) Transfer coins between users.

(c) Interaction with the user (ie user interface).

Each function typically involves some operational entities (such as authorities, exchanges, wallet providers, and payment system operators) and core technology infrastructure (such as distributed ledger technology (DLT) and smart contracts). Furthermore, the standards can be implemented by a central management entity or by an automated technology protocol. For a more detailed description of the Stabilizingcoin ecosystem, please see Annex A.

The value of a stable currency is usually related to the portfolio of assets or underlying assets. However, the design of a stable currency is significantly different depending on its exchange rate policy relative to sovereign currency (fixed or variable), the nature of the claims held by the user, the redemption commitments provided by the stable currency provider, and the type of assets used.

At least three design models have emerged. First, the face value of the commonly used accounting unit when the stable currency is issued. The user's asset to the issuer or potentially directly required, and the supplier promises that the same currency in the face value of the coin is used to purchase the coin. The assets in this model are usually mobile. In the second model, the stable currency is not issued at a specific denomination, but forms part of the underlying asset portfolio, as in an exchange-traded fund (ETF). In the third model, coins are backed by claims against the issuer. The value of 4 coins is rooted in public trust in the issuer (and related regulators).

1.2 Improve payment systems and services

-

The Stabilizingcoin program highlights shortcomings in cross-border payments and access to trading accounts. -

Depending on their design, a stable currency system can increase payment efficiency, provided they are interoperable and benefit from a level playing field.

In most cases, domestic payments are more and more convenient, and they can be used 24/7 in real time. However, cross-border payments are still slow, expensive and opaque, especially for retail payments such as remittances. The current challenges of cross-border payments are described below.

The recent Stabilization Coin program highlights these shortcomings and highlights the importance of improving access to financial services and cross-border retail payments. In principle, retail stable coins can implement multiple payment methods and serve as a gateway to other financial services. By doing so, they can replicate the role of the trading account, which is a stepping stone for broader financial inclusion. The Stabilization Coin Initiative also has an incumbent financial institution that is challenged to increase the market potential of competitive potential. However, the positive impact on competition is based on a fair competitive environment and system interoperability to avoid introducing new barriers to entry.

However, for stable currency to meet the need for no bank accounts and insufficient services, they must first prove to be a safe storage value, ensure high levels of protection and legal certainty for their users, and comply with relevant regulations. In addition, they will have to overcome the current barriers to restricting access and use of trading accounts.

Cross-border payment challenges

Many cost factors and other challenges affect the delivery of cross-border retail payments. These cost factors include agency bank fees, foreign exchange fees, telecommunications charges, program fees, and exchange fees. In addition, legal, regulatory, and compliance costs are considered to be significantly higher than domestic retail payments.

AML/CFT and sanctions compliance are essential to maintaining financial integrity and protecting the global financial system from abuse by money launderers, terrorists and other bad actors. However, they may therefore increase the cost of cross-border payments, especially when there are differences in rules or requirements between the jurisdictions involved and the required precautions (customer due diligence, sanctions screening, etc.) are completed multiple times in different steps. Especially in the trading chain. While it is important that the rules properly accommodate differences between jurisdictions, better coordination of these detailed requirements and improved international cooperation and information sharing can help alleviate this pain point. Although there is no specific cross-border payment, the risk of money laundering and funding for terrorism is generally considered to be high in a cross-border context because of more complex participation.

In addition, payment service providers (PSPs) may struggle to interoperate due to a lack of standardization. Standardization and interoperability are important catalysts for seeking efficiency and achieving economies of scale and network effects for cross-border retail payments. Some initiatives, such as the development of ISO 20022, aim to achieve this goal. However, while international standards can improve efficiency and interoperability, they cannot be fully realized if they are interpreted and implemented differently in different jurisdictions. Just as PSPs may be difficult to interoperate due to the lack of standardization of messaging formats, back-end service providers may also have difficulty transmitting and coordinating transactions for the same reason. If the information and content or format of the payer's PSP does not meet the information required by the payee's PSP, then messaging will pose a challenge to cross-border retail payments.

PSPs and back-end service providers that add complexity and risk by conducting foreign exchange transactions. These additional complexities require management and risk mitigation, which increases costs (the way is neither opaque nor predictable) and reduces the speed of an overall transaction. Another factor is that the fast, efficient processing of cross-border retail payments is a different time zone and leads to a world of divergence around the open time of the payment system.

A major obstacle to differing in the interconnection of domestic payment systems and/or in the development of shared global payment platforms is the legal framework of each jurisdiction and the involvement of cross-border operations in interrelated or shared payment platforms that lead to contractual obligations Perform related uncertainties.

Improving the domestic payment infrastructure can remove many of the pain points that are current experience for users and businesses. Still, the significant challenge will still be to make cross-border payments expensive, slower and less transparent.

Many public sector projects are trying to alleviate these pain points so that international payments are as seamless as domestic payments. The main goals of official sector projects tend to focus on improving efficiency and interoperability, enriching data, extending functionality, increasing work time and access, and introducing faster (real-time) retail payment tracks. For example, using a Legal Entity Identifier (LEI) helps to quickly identify parties in a transaction and reduces AML / CFT compliance costs.

2. Risks and challenges of public policy, supervision and regulation

-

Stabilizing the currency poses many challenges and risks to public policy objectives and the supporting regulatory and supervisory framework. -

The Administration expects stable coin developers to adopt the highest standards to deal with risks before their arrangements begin to operate.

From the perspective of public policy, supervision and supervision, stable currencies pose a range of potential challenges and risks. A basic challenge is that the arrangement of stable currencies is different, and the opportunities and risks they bring depend on the infrastructure and design of each stable currency arrangement. In other words, there are some commonalities between them.

Some of the risks – examples of payment systems in terms of security and efficiency, money laundering and terrorist financing, consumer/investor protection and data protection – are familiar and can be solved, at least in part, existing regulation, supervision And within the supervision framework. However, given the nature of certain stable currencies, their implementation and implementation may involve additional complexity. Stabilizingcoin arrangements should conform to the same standards as traditional payment systems, payment schemes or payment service providers and comply with the same stringent requirements (ie the same activities, the same risks, the same regulations) to ensure their design and safe operation Effectively meet public policy goals. In addition, some of the economic characteristics of stable currency arrangements are similar to the regular activities performed, through the payment system, exchange traded funds, money market funds (money market funds) and banks that may be useful for understanding the function of the stable currency. risk. The government authorities expect stable coin developers to deal with such risks before their projects are put into operation.

Stabilizing currency arrangements may also present risks beyond the existing legal or regulatory framework. Stabilizing coins may combine new technologies, new entrants to financial services and new service offerings. Retail Stabilized Coins, due to their publicity, high volume, possible use of micropayments and potentially high pass rates, can be offered to a limited user group to stabilize the currency to a different risk than the wholesale price. Policy makers are aware of the responsibility of adapting existing rules and introducing new ones when needed.

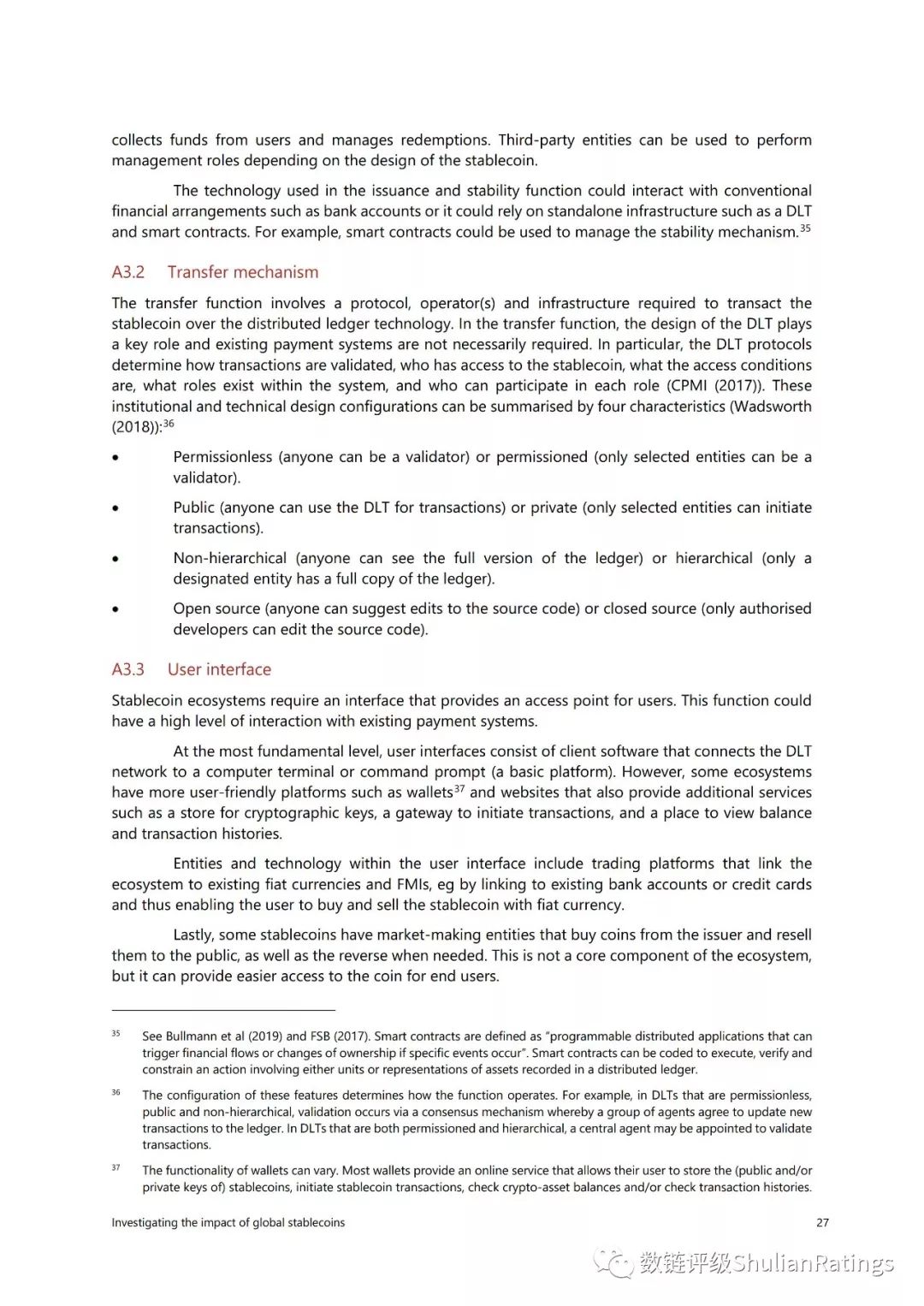

Stabilized coins from large existing platforms, such as large technology companies, can scale quickly due to their established global customer base and links to platforms that provide easy-to-access interfaces. The potential to become such a global arrangement brings risks beyond the small-scale stable currency arrangement and therefore more public policy challenges now – including those for the safety and efficiency of the overall payment system, competition policy, financial stability, monetary policy transmission And the long-term impact on the international monetary system (for an analysis of large technologies and payments, see Annex B).

2.1 Legal, regulatory, supervisory and public policy issues, regardless of size

2.1.1 Legal certainty

- Establishing a sound, clear and transparent legal basis in all relevant jurisdictions is a prerequisite for any stable token arrangement.

A well-established, clear and transparent legal basis is a core element of payment, clearing and settlement arrangements. A stable currency must be defined and managed, with clear legal provisions to support and certainty and predictability, and how the underlying technical arrangements of the material are used by the parties. However, the stability of the currency and the underlying technology and contractual arrangements may vary significantly, and the applicable legal system depends on the key in the particular design and characterization. The ambiguity of rights and obligations may make stable currency arrangements vulnerable to loss of trust (affecting financial stability). Users must give confidence to the stable currency that will be used as a stable advertisement in practice. If value stability depends on market mechanisms, then the market broker's legal obligations must be defined to ensure that liquidity is always available to all customers.

With regard to the legal characteristics of stable currencies, the most relevant decisive factor is whether they are considered equivalent currencies; classified as contractual or property rights; or have rights to issuers or related assets. In some areas, stable currency may constitute a security or financial instrument, for example as a debt instrument, or to express interest in a fund or collective investment vehicle, and will be subject to applicable laws regarding securities and financial instruments.

Because of the need to determine which jurisdiction's laws apply to the various elements of the overall design, and which jurisdiction's courts have the ability to resolve disputes, specific issues may arise in cross-jurisdictional situations. Legal conflicts may also arise in view of the different treatments in different jurisdictions. In some jurisdictions, applicable financial sector laws may not be able to keep up with new business models and market activities, such as stabilizing coins. Some recent initiatives by national authorities are working to resolve this uncertainty.

If an arrangement relies on DLT to record and transfer monetary value, the legal basis for such an arrangement must be carefully considered, and such an arrangement must be at least as robust as a traditional system. For example, the parties involved in the rights and obligations of the legal basis and the final settlement must always be clear.

2.1.2 Governance sound

-

Before doing real-time operations, you must clearly establish sound governance.

Sound and effective governance can increase the security and efficiency of payments and related services. The governance structure of the arrangement must also be clearly defined and communicated to all ecosystem participants. Good governance can also support a broader financial system for stability and consideration of other relevant public interests (eg, through the design of arrangements that increase decision-making or through broad participation of stakeholders).

Arrangements that rely on intermediaries and third-party providers should be able to review and control the risks they bear from other entities and the risks posed to other entities. This may be particularly important if the device includes a variety of entities with specific tasks and responsibilities that are not necessarily within the scope of regulation. These entities may still be interdependent and some of them may be interlinked with the entire financial system.

In the case of DLTs used in the arrangement, careful responsibilities and accountability and recovery procedures are required. Sound governance may be the case with a permissionless DLT system, especially challenging – systems that are not dispersed by responsible entities may not be able to meet regulatory and supervisory requirements. On the other hand, a highly complex governance structure can hinder decisions about layout design and technology development or can slow down the response to operational events.

If the reserve asset is not differentiated from the equity of the stable currency issuer, the investment policy may be abused to privatize the asset gain, and the asset loss will be socialized to the token holder.

2.1.3 Financial Integrity (AML / CFT)

-

Public agencies will apply for the highest international standards with virtual assets and their suppliers for anti-money laundering / counter-terrorism financing. -

The Group of Seven will lead by example to implement the revised FATF standards related to virtual assets quickly and effectively .

Without effective regulation and oversight, encrypted assets, including stable currencies, can create significant financial integrity risks that could create new opportunities for money laundering, terrorist financing and other illegal fundraising activities. To alleviate these risks, it is a stable currency that provides stability to the currency and other entities. The ecosystem should comply with the financing of the highest international standards for anti-money laundering/counter-terrorism financing and weapons proliferation against mass destruction (CPF). In some stable currency arrangements, the possibility of peer-to-peer trading is an additional risk that should be considered.

The Financial Action Task Force (FATF) is the international standard setting body for AML/CFT/CPF. The Task Force provides a strong and comprehensive framework to combat money laundering, terrorist financing, financing diffusion and other illegal financing of countries, financial institutions and designated non-financial businesses and industries. While recognizing the importance of responsible innovation, the FATF is also committed to ensuring that its standards are aligned with emerging risks. In October 2018, the FATF adopted changes to its recommendations to clarify that they apply to financial activities involving virtual assets and virtual asset service providers. These changes were supplemented by an explanatory note and the latest guide in June 2019.

It is essential that international standard setters, including the FATF, continue to keep in touch with market participants to keep abreast of developments and are ready to review their recommendations to ensure that all illicit financing risks are appropriately mitigated. G7 supports the FATF framework and the ongoing review of FATF standards by countries and their ongoing efforts to ensure that FATF standards require countries and financial institutions to understand and mitigate the risks associated with new technologies, including new finance. Product or service. Additional work may be needed to further clarify the extent to which regulatory requirements cover various activities in the stable currency ecosystem.

2.1.4 Security, efficiency and integrity of the payment system

-

Effectively monitoring and overseeing the stable currency system is critical to achieving public policy goals for the security and efficiency of payment systems. -

It is expected that the regulatory and policy framework will remain technology neutral and will not hinder innovation while ensuring its safety and reliability.

The smooth operation of the payment system is critical to the financial system and the economy as a whole. Individuals and companies need accessible and cost-effective payment methods. The system benefits business by promoting business activities and promoting economic growth. Financial markets rely on reliable clearing and settlement arrangements to allocate capital and manage liquidity.

However, improperly designed and operated payment systems can lead to systemic risks that can adversely affect the real economy. Without proper management, in the case of payment problems, the system can cause or exacerbate financial shocks – for example, as liquidity misalignment or credit losses more widely affect the stability of the financial system. Interdependence can also be an important source of systemic risk.

For these reasons, the central bank and other relevant departments at one level have tasks to ensure that the functionality of the system is paid in a safe/efficient manner at all times. These public policy objectives are reflected in the Financial Market Infrastructure Principles (PFMI) developed by the Payment and Market Infrastructure Committee (CPMI) and the International Securities Commission (IOSCO) (CPMI-IOSCO (2012)). . Legal, management and operational risks (including the network) are all relevant to payment systems and other types of financial market infrastructure (FMIS). Among other things, PFMI provides guidance to address these risks and ensure the efficiency of FMI, including systemically important payment systems. PFMI also covers credit and liquidity risk, which is especially important when considering the design of wholesale payment arrangements.

The regulatory and policy framework is expected to remain technology-neutral rather than hinder innovation while ensuring that it is safe and robust. Stabilizing currency arrangements are expected to meet the same standards and comply with the same requirements as traditional payment systems, payment schemes and payment service providers (ie the same activities, the same risks, the same regulations). Innovation should support interoperability and seek to mitigate system interdependencies.

2.1.5 Network and other business risk considerations

-

Public authorities will require the use of appropriate systems, policies, procedures and controls to mitigate the operational and cyber risks posed by stable currencies.

Network and other operational risks may be realized in different components of the stable currency ecosystem, including the technology infrastructure for value transfer. Operational resilience and cybersecurity are core aspects of payment system security. For consumers, some crypto asset wallets and trading platforms have proven vulnerable to fraud, theft or other network events. Network events, including for crypto asset trading platforms, are on the rise, leading to significant losses to customers. Although distributed ledgers may have availability and integrity capabilities that make them more resistant to certain operational and network risks than centralized managed ledger systems, the structure of distributed ledger systems may also be compromised. May damage the system. Moreover, new technologies may face operational risks that have not yet been determined.

Stabilizing coins may be subject to laws, regulations and guidelines, and may also fall within the scope of international standards for operational risk. For example, the International Organization for Standardization (ISO) and the International Electrotechnical Commission (IEC) provide information security management standards. National frameworks, for example as a cybersecurity framework, are provided by standards published by the National Institute of Standards and Technology (NIST), guidelines and best practices to manage cybersecurity-related risks, which may be applicable to stable currency and other crypto-asset ecosystems. system.

Where Stabilized Coins are arranged to use DLT, any distributed settings inherent to the potential benefits and disadvantages come into play. Using multiple simultaneous ledgers and multiple processing nodes reduces the risk of a single point of failure.

However, the complexity of distributed ledgers can hinder the scalability of operations. Payment arrangements typically require significant fluctuations in the volume of transactions and therefore need to be scalable in business. The use of multiple simultaneous ledgers and multiple processing nodes may be limited when ensuring real-time processing of transactions on distributed ledgers. 2.1.6 Market Integrity

-

Stabilizing currency arrangements must ensure fair and transparent pricing in the primary and secondary markets.

Market integrity is the definition of the fairness or transparency of financial market price formation, which is an important basis for protecting investors and consumers as well as competition. Since stabilized coins are designed to reduce the volatility of their prices relative to fiat currencies, there may be fewer opportunities for price manipulation than other crypto assets. 11 However, it is unclear how to determine the price of certain stable currencies, which depends to a large extent on the specific design of the stable currency arrangement. In some designs, agents (such as designated market makers) may have significant market power and the ability to determine the price of a stable currency, and may abuse the market.

The stability of the price of the stable currency in the secondary market depends, among other things, on the degree of trust that market participants will have in the ability and willingness of the issuer to exchange their expectations for Fiat at a consistent value with reasonable users. Twelve additional risks may appear for stable currency. This should be linked to the portfolio, and its composition can be changed by the issuer over time. If the investor knows (or guesses) about the will of the stable currency issuer to rebalance the basket's assets, they can run their purchase request by concatenating them with their stable currency investment/redemption purchase and sale assets.

Finally, companies in the stable currency ecosystem may face conflicts of interest in a manner similar to what may occur with some existing cryptographic asset trading platforms. For example, they may be motivated to disclose false information about their activities, such as the number of customers and the volume of transactions for advertising and other purposes. In addition, stable currency issuers may intentionally (or unintentionally) mislead customers about the key functions they perform, for example, as the way they manage the mortgage assets. These types of false information can lead to pricing errors and market failures. Since it is a single entity that can play multiple roles, such as market makers, trading platforms and custody wallets that do not see the way in other markets in the ecosystem, the risks of the entity and the effects of market misconduct may be amplification.

2.1.7 Data Protection

-

Applicants will apply appropriate data privacy and protection rules to stable currency operators, including how participants in the ecosystem use data and how data is shared between participants and / or with third parties.

As more and more data is collected and used to provide financial services and the development of machine learning and artificial intelligence technologies, policy issues surrounding personal and financial data protection and privacy will become increasingly important. Data policies are difficult to coordinate across borders, especially when there are different laws and regulations across jurisdictions and different cultural perspectives on data protection and privacy. In 2019, Japan assumed the presidency of the G20, confirming the importance of establishing global standards on how to define, protect, store, exchange and trade data (G20 (2019)). The International Conference of Data Protection and Privacy Protection Commissioners provided a forum for discussion between national data protection authorities. Data privacy laws should aim to address key technical issues such as: (i) identification data definition and processing; (ii) scope of entities covered by law; (iii) consent methods, data portability and correction of inaccurate data Rights (Petralia et al. (2019)).

Stable currency

Users may not have clear information about how their personal data will be used by the participants' ecosystems and how they will be shared among participants or with third parties. Operators of different categories of stable currency and user profiles that further process the collection of data may give rise to additional privacy considerations. Finally, some data protection issues may also arise from the use of technology, which makes certain certain consumer rights of the campaign, such as deleting user data or seeking to pursue unauthorized transactions, more difficult. For example, the DLT used should be compatible with legal principles, etc. as a "right to be forgotten" (which has) (Fink (2018)).

2.1.8 Consumer/Investor Protection

-

As with any emerging technology, additional work may be required to ensure that all significant risks and their individual obligations are communicated to consumers and investors. -

If a stable coin Considered to be a safe or a financial instrument, market participants must comply with the relevant capital market legal framework.

Given the complexity and novelty of stable currency arrangements, users (especially retail users) may not fully understand the risks. Therefore, regulators should consider the extent to which existing consumer protection or investor protection legislation applies, and if not, ensure that all actors involved in the ecosystem safeguard basic consumer and investor rights.

To make informed purchasing decisions, consumers/investors should give information and disclosures about the nature of the stable currency, and the rights associated with them and the risks they have so far. Therefore, the need for regulation (such as good law) clarity to protect consumers and investors, and to see that enough information and disclosure are available. For example, if a stable currency constitutes a security or a financial instrument, then the relevant securities laws will apply, it may not be possible for the issuer to issue and subsequently legally trade the stable currency without a prospectus or similar disclosure document Describe the issuer, its operations and its risks. Similarly, the party's liquidation and settlement of the stable currency may be subject to the requirements of the relevant custody and clearing institutions.

If there is an unauthorized payment from a stable currency account, there should be a clarity on what kind of rights holders have a refund for the claim and clearly state how to get a refund. As observed in the broader crypto asset market, the potential for misleading marketing and mis-selling may exacerbate concerns about information and consumer understanding.

2.1.9 Tax compliance

-

Stabilizing currency operators and users and other interested parties should comply with applicable tax laws and mitigate potential tax avoidance obligations.

Stabilizing coins, like other crypto assets, can pose two types of challenges to tax authorities. First, the legal status of the stable currency is uncertain, so the tax treatment of using stable currency for trading is uncertain. For example, a stable currency transaction can handle a foreign currency similar to the balance of payments, and a sales tax that is attractive to the transaction. In addition, the stable currency can be regarded as a safe, stable currency with a potential value when the tax is volatility relative to the fiat currency. In this case, tax redemption may be required when redeeming a stable currency. Several countries have issued guidance for taxpayers engaged in crypto asset transactions. However, the comprehensiveness of the guide is different. Different tax treatments across jurisdictions complicate the tax treatment of stable currencies.

The second challenge for tax administration authorities is that stabilizing coins (like other crypto assets) can also promote tax avoidance obligations. Jurisdictions can apply for terms and obligations of financial institutions to the operator's stable currency arrangement, but the lack of a central intermediary in the DLT system can make this difficult to implement. In addition, the degree of anonymity provided by the stable currency arrangement can make it more difficult for the authorities to track transactions and to determine the stable currency of the beneficiary owners, making it more difficult to identify tax evasion.

2.2 Internal Public Policy Challenges for Potential Global Stabilization Coins (GSCs)

-

If the stable currency reaches a global scale, the public policy challenges discussed will be magnified. -

If the stable currency reaches global scale, it will bring other public policy challenges.

Some of the risks, the above are magnified into a stable currency growth and reach a global scale. Because a GSC is likely to be a systemically important and concentrated risk, the security, efficiency and integrity of the payment system are critical. A GSC arrangement is expected to have emergency arrangements to support ongoing services. In addition, GSC arranges the service as a system for large-value payments that may result in additional credit and liquidity risk over-concentration of the bank's real-time payment settlement payment system. Stabilizing coins may expand into payment methods, which can exacerbate the risk of money laundering and other illegal financing. In some GSC arrangements, the possibility of peer-to-peer trading is an additional risk that should be considered. Network risk may be amplified because the GSC may provide a larger attack surface for potential malicious actors, thereby compromising the confidentiality, integrity and availability of the ledger. As the organization behind GSC can quickly become the custodian of millions of users' personal information, data privacy and protection issues are receiving increasing attention. Providing an appropriate level of consumer/investor protection becomes more challenging, because a GSC in a transnational nature means that it is subject to a different regulatory jurisdiction in a different framework.

2.2.1 Fair competition in financial markets

-

From a competitive perspective, innovation in financial services is expected to lead to a better user experience and a wider access to financial services. -

Some of the GSC arrangements that have emerged , however, may weaken the competitive financial markets. -

The GSC should support competition and interoperability with other payment systems.

Competition policy aims to promote market innovation and efficiency. In order to achieve these goals, the authorities will monitor the market for signs of anti-competitive behavior and seek to detect, investigate and resolve cartels, abuse of dominance or monopoly and anti-competitive mergers.

The introduction of innovative financial products can promote competition and more choices, and consumers are challenged by the dominant financial institutions in the market. However, the GSC may pose a challenge to competition and antitrust policies, especially if the GSC arrangement leads to a large market concentration (BIS (2019)).

GSC arrangements can achieve market dominance, as data that was initially motivated by them to adopt, the large network of fixed costs and the strong network effect benefits of the index required for large-scale business operations. The GSC may affect market competition and level play if the GSC arrangement is based on a proprietary system, as this may be used to prohibit anyone from entering or increasing barriers to entry into the system. This situation may be the key channel for scheduling control in the case of stable currency companies is the use of consumers and businesses to access a range of services.

Competing authorities are taking good, last, general policy positions in various jurisdictions with coordination and individual market conditions. In June 2019, a "common understanding" document published in the G7 jurisdiction of the competition authorities "competition and the digital economy" recognizes that the advantages of the digital economy will be maximized in a highly competitive market (G7 (2019b)). Fourteen strong competition frameworks can help promote the benefits of digital transformation while protecting the market for consumer trust. Antitrust and law enforcement leaders come together in various international forums to discuss how traditional competition enforcement methods can be adapted to address environmental and digital issues.

-

In each GSC and its ecosystem, there may be vulnerabilities such as credit risk, maturity and liquidity mismatch or operational risk. -

This is important to see in a stable coin Arrange as a whole as well as for the various components in it. -

GSC may potentially affect financial stability by increasing the vulnerability of the traditional local currency financial sector and promoting cross-border transmission of shocks. -

The disruption of the GSC may eventually affect the real economy of multiple countries.

Vulnerability within specific components of GSC

The mechanisms used to stabilize the value of GSC will need to be incorporated into high standards of financial risk management to address market, credit and liquidity risks. If the risk is not adequately addressed, this can undermine confidence and trigger a standard operation similar to bank deposits, in which case the user will attempt to redeem their GSC with reference values.

GSC's reputation is highly dependent on the credibility of the agreement itself, which means that events that undermine the reputation of the GSC agreement may result in sudden sales out of the GSC. GSC is dependent on market makers to stabilize the price of the open market in the GSC may be vulnerable if these market decision makers are not obligated to stabilize the price in all cases and may withdraw from the GSC A market that withstands strong selling pressures. Even though GSC is committed to fulfilling redemptions, this can be fragile to a lost confidence and a run may result. Such a situation would be easier if, for example, the GSC issuer is not transparent about its reserve holdings or if the report in the GSC lacks credibility. Poor governance, such as non-segregated funds in reserves, the issuer’s legal obligations are ambiguous or misunderstood, or the mechanism by which stable currency holders can realize or redeem value from the issuer is weak and may lead to GSC Easy to suffer from loss of funds or loss of confidence.

The assets referenced in the GSC include bank deposits, potential banks that can be exposed to credit risk and liquidity risk. A default or liquidity issue at the bank may mean that the GSC cannot meet the redemption requirements. GSCs holding a wide range of assets, such as bonds, may face market and liquidity risks of these assets and the issuer's credit risk. A decline in the value of reserve assets triggered by a particular change in overall market conditions or the underlying value of assets may reduce the value of GSC. In addition, if the GSC is to have a nominal value, the value of the falling reserve asset may result in a nominal and reserve value between the gaps. This gap may trigger an operation in which the user attempts to redeem his or her own GSC as the underlying asset, which may require the issuer to liquidate its assets below market value (fire sales). GSCs holding more assets will require liquidity arrangements to ensure that funds are available to redeem redemption even if the stable currency is under heavy selling pressure.

Vulnerability in the overall stable currency system

It is important to consider the arrangement of the stable currency as a whole and consider its various components. The governance between components and the relationship between them can be complex. As a result, vulnerabilities may arise if the different components between obligations (such as between issuers and market makers) and responsibilities are not clear.

There may also be unpredictable interactions between components after destroying any individual component. This complexity can make end-to-end risk management difficult and blur the financial risk tolerance of the entire system without proper control (for example, between central governance agencies, reserve managers and wallets) . In addition, the location, extent and transferability of loss absorption capacity between different components may be unclear, or legal or operational difficulties may be encountered in crisis situations.

Impact on the Vulnerability of the Broader Financial System GSC can increase vulnerabilities in the broader financial system through several channels. First, if a user holds a permanent GSC in a deposit-type account, retail deposits at the bank may decline, increasing the bank's reliance on more expensive and volatile sources of funds, including wholesale funds. In countries where the currency is a reserve, some of the deposits drawn from the banking system (when retail customers purchase GSC) may be converted into domestic bank deposits and short-term government securities. This means that some banks may get larger wholesale deposits from stable currency issuers rather than large amounts of small retail deposits.

Second, when confidence in one or more banks is eroded, readily available GSCs may exacerbate bank operations. In addition, depending on where and how the reserves are deposited between banks, some banks may experience changes in the allocation of funds (ie, increase or decrease in total deposits), the effect of which is difficult to predict.

Third, if the new financial intermediaries capture a significant portion of the financial intermediation activities in the GSC ecosystem, this may further reduce the bank's profitability, which may lead to more risk to the bank, or a contractual loan to The actual economy. This is a country that has the potential to particularly affect smaller banks and banks with non-basket currencies. While it is not possible for public authorities to protect banks from competition or technological advances, they need to be assessed and managed.

Fourth, depending on the level of absorption, the purchase of a safe asset with a stable asset reserve may result in a lack of quality liquid assets (HQLA) in certain markets, which may affect financial stability.

In many countries, a basket of stable currencies linked to foreign exchange may form a more stable currency than domestic ones. Stabilizing Coins This is a claim or has links to potential assets that may be offered to major currencies and developed market assets that can be considered more stable than at home. As a result, in the domestic financial instability, the public can run on a specific GSC (similar to sudden dollarization). The transfer of a domestic bank account to a GSC arrangement that primarily has foreign assets (depending on where it is located) may result in capital outflows to the country. The speed of a GSC transaction may be an ideal function during normal times, but may be destroyed during periods of turmoil. The authorities may lack the time needed to effectively intervene to stop this destructive process, and the GSC may act as a highway for capital outflows.

Transferring risk to the real economy If a GSC becomes a widely used means of payment, any interference to payment may ultimately harm the real economy. If GSC is used as a means of settlement within the financial market, such delays may present additional financial stability risks. The impact will depend on the extent to which other payment systems (including cash) can be substituted.

If the value of the GSC declines, banks and other financial institutions that are in direct contact with the GSC (for example, because they hold GSC services to their customers) may suffer losses. If there is no deposit insurance and last lender function, these intermediaries will be more susceptible to run. In addition, disruptions in these intermediaries may undermine confidence in the entire GSC system.

GSC's reserve assets may be large, which has a major impact on financial markets. Large-scale purchases or sales of other assets (such as bonds) are movable prices (and yields) in those markets. In extreme cases, if the issuer must sell the assets in a quick order to meet the redemption requirements in a pair of GSC points, price cut sales may result in, and may confuse the escrow bank's funds. Finally, under the pressure of time, if a GSC provides an alternative fiat currency, it may undermine monetary sovereignty.

2.2.3 Monetary policy transmission

-

The impact of GSC on monetary policy delivery will depend on the use of stable currency as a means of payment, value storage and / or accounting units, and the role of specific currencies in stability mechanisms. -

If GSC is widely used as a value store, it may undermine the impact of monetary policy on domestic interest rates and credit conditions, especially in countries where the currency is not part of the reserve assets. -

GSC may increase cross-border capital flows and affect the transmission of monetary policy. -

Considering the inability to discuss sovereignty over sovereignty over the impact of such alternatives on public policy, currency substitutions to the GSC may have a different impact on foreign legal tenders (classic dollarization).

The impact of monetary policy on domestic interest rates and credit conditions

Use GSC as a value store

If GSC is widely used as a value store, GSC-denominated assets will remain in the company's and household's balance sheets. In this case, the impact of domestic monetary policy may be weakened because it may have limited impact on the earnings of the assets held by GSC. This impact will depend on the design of the GSC and the scope of the GSC, and whether there is a currency intermediary in the GSC (as described below).

If a GSC pays once, any impact on the transmission of monetary policy through the interest rate will depend on how the rate of return is determined. This benefit may reflect the return on assets in the reserve basket. In this case, if the national currency is the only asset in the basket, the GSC holdings will equal the interest rate of the national currency deposit (possibly minus some fees). Therefore, if there is, the transmission of domestic monetary policy through interest rates may be less affected. Conversely, if multiple currencies are in the basket, the GSC increase in return may be a weighted average of interest rates on the GSC reserve currency, weakening the link between GSC-RMB domestic monetary policy and interest rates. This is especially the case when the national currency is not included in the reserve asset basket at all, as is the case in most economies in the world.

In countries where the value of the local currency is unstable and the payment infrastructure is imperfect, the impact may be even greater. In these countries, the GSC pegs assets in a currency that is more widely used as a means of payment and savings than other domestic currencies, even if there is no return on the GSC, thus reducing the effectiveness of monetary policy. This will also result in a reduction in the central bank's seigniorage tax revenue (and government-related fiscal revenue). These effects will be similar to those already occurring in the country where the amount of cash used has declined due to dollarization. However, currency substitution can have a different impact on the GSC than on foreign fiat currencies (classic dollarization), giving a discussion that cannot be held by such a public policy meaning sovereign to sovereignty.

In addition, since domestic savers will be able to convert between local currency deposits and GSC holdings, the return of GSC may affect the amount of local currency deposits, thereby affecting the deposit and loan interest rates in the local currency financial system, thereby further weakening domestic banks. Effectiveness. The interest rate channel is the monetary policy. This is similar to the effect that has led to dollarization in some countries, but may be achieved for other countries that are not currently dollarized.

If the GSC user permanently saves the GSC in a class deposit account, the bank retail deposit may be reduced, thereby increasing the bank's reliance on wholesale funds. This may exacerbate the transmission of monetary policy, as wholesale deposits are generally more sensitive to interest rates than “sticky” retail deposits. However, greater reliance on wholesale funds may make banks facing a more volatile deposit base more cautious about loans, especially longer-term loans.

Use of GSC in financial intermediation

In the above discussion, GSC is considered a form of savings, but intermediaries between depositors and borrowers continue to operate in local currency and the domestic financial system. However, an intermediary may appear to borrow (or accept a deposit) in the GSC and lend the coin to the borrower (thus "creating" the currency). This will further weaken the transmission of domestic monetary policy, as the return on domestic depositors and the interest rates paid by domestic borrowers will be weaker on monetary policy.

Cross-border transfer of international capital flows and monetary policy

By facilitating cross-border payments, GSC may increase cross-border capital liquidity and the substitutability of domestic and foreign assets, thereby expanding domestic interest rates' ability to respond to foreign interest rates and undermining domestic currency controls.

Use GSC as an international payment account unit

As long as trade continues to be denominated in conventional currencies, the use of GSC as an international means of payment does not necessarily change the response of international trade to exchange rates. However, if a GSC becomes an accounting unit for international trade and the trade in the GSC is invoiced, the international price in the GSC may become sticky. The terms of trade will then depend on the value of the GSC for the local currency and not on the bilateral exchange rate between the trading partners' local currency. As a result, the impact of exchange rates on trade and economic activity can be eliminated – a result similar to the results often attributed to the pricing of US dollar international trade.

GSC and international asset holdings

If the GSC is widely used globally, the demand for those assets included in the reserve basket may increase in the long run. This may require capital outflows from countries that are not included in the GSC reserve basket, and capital inflows in countries where their assets are included. This may raise the market interest rate in the former country and lower the latter in the latter. As eligible collateral becomes scarce, any shortage of HQLA generated may undermine open market operations.

3. Legal, regulatory and regulatory framework applicable to GSC

-

Standards-setting bodies are stepping up their efforts to assess how their existing principles and standards can be applied to stable currency arrangements and / or to develop new policy recommendations for stable currency arrangements.

Due to the related technology, the GSC of management arrangements and usage is at an early stage of development, it is not yet clear what design choices will be made for specific GSC arrangements. In some cases, GSC developers are required to provide additional information to fully assess how the regulations are implemented. However, the functions performed through the ecosystem – ie the issuance and stabilization of coins, the transfer of coins, and in the user interface – will be comparable to existing regulated financial activities, they will pass through separate entities, which will be subject to specific regulations Conducted in different jurisdictions. While their design in novelty means that they may not be suitable for easy entry into existing regulatory definitions and structures, the authorities expect the GSC to be subject to one or more regulatory frameworks.

Clearly, existing financial integrity, data protection, and regulatory frameworks for consumer and investor protection will apply to GSC. However, the components of a GSC arrangement may belong to different types of regulatory and prudential institutions and/or systems. Services that provide payment services, custody, distribution and transactions may fall into the scope of different regulatory categories (Box 2). A GSC may also qualify as a unit in a collective investment plan or for electronic money (electronic money). Whether a GSC constitutes a security or financial instrument in a particular jurisdiction will depend on the characteristics of the GSC and the applicable law.

Therefore, appropriate regulatory approaches may require cross-border and inter-agency collaboration. Therefore, the authorities are carefully considering the most appropriate regulatory measures and how and should apply the existing financial regulatory framework and assess the economic and technical characteristics of the stable currency. In addition to the regulation of the various components, the entire GSC ecosystem may also be systemically important. If so, it will be important to consider how the regulatory framework can be applied to the ecosystem as a whole. For example, a GSC arrangement in the entirety can constitute a payment system, critical infrastructure or additional regulatory services that are forced by the central bank and other public authorities in different jurisdictions to supervise or supervise financial service providers.

Currently, many existing standards and practices will apply to systemically important GSCs. CPMI-IOSCO PFMI aims to improve the security and efficiency of payment and settlement arrangements, including assessment and monitoring methods. PFMI clarifies the high-level principles (and some specific quantitative minimum requirements) for identifying and managing risks in the Multilateral System among participants, including system operators, for clearing, closing or recording payments, securities, derivatives Tools or other financial product transactions. PFMI is neutral in jurisdiction, organization and technology (CPMI-IOSCO (2012), CPMI (2017)). CPMI-IOSCO has also developed a GSC-related Financial Market Infrastructure Network Resiliency Guide (CPMI-IOSCO (2016)).

In order to mitigate risk of cross-border regulatory arbitrage, this is an important sector to strengthen cross-border cooperation and to assess existing international standards, such as applicability as in the FATF standard PFMI, in Basel III standards, And the relevant SEC organizes standard securities markets.

Standard setting bodies are stepping up their efforts to assess how their existing principles and standards can be applied to, and/or develop new policy recommendations for stable currency arrangements. The work of the Basel Committee on Banking Supervision on cryptographic assets includes: (i) the development of high-level regulatory expectations for exposures and services related to banks and cryptographic assets (BCBS (2019)); (ii) continuous measurement of banks' risk of cryptographic assets Exposure; (iii) potential specifications for the prudent handling of banks' encrypted asset exposures. IOSCO's work includes evaluating which principles and standards of IOSCO may apply to Stabilizingcoin recommendations, especially GSC, including: policy recommendations for money market funds; ETF principles; protecting customer assets; regulatory considerations related to crypto asset trading platforms Cooperation and mitigation of market fragmentation. The CPMI is currently considering how private digital tagging arrangements may also be used to address wholesale transactions for that settlement and seek to understand the uncertainty of legal treatment in cryptoassets. However, it is important that some participants in the GSC may or may not be covered by the existing financial regulatory framework, even if the other parts of the arrangement are technically covered by the existing framework. Therefore, it is necessary to thoroughly evaluate the regulatory gap before launching a potential GSC.

In the Financial Stability Board (FSB) program to assess, in cooperation with standards-setting bodies, it is possible to be a regulatory blank around the GSC and to provide its results to the G20. The work will include an effective regulatory approach to the relevant authorities and an emerging approach to inventory, as well as cross-border coordination and cooperation on the need for advice. The FSB will also collect information about specific aspects of GSC and cross-border issues, review potential regulatory and supervisory approaches to address financial stability and systemic risk concerns, and as an additional multilateral response to the need .

Overall, it will be important for the department to check what kind of legal status should be granted in the respective regulatory framework to the relevant legal entity, in full understanding of the role of the details, such entities play within the GSC ecosystem. Although these assessments can be naturally different, jurisdictions rely on existing financial regulatory frameworks, and all or part of these entities may be subject to one or more existing frameworks. Cross-border and inter-agency collaboration can help to better capture risk and ensure consistent regulation of comparable entities.

Payment system

Systemically important GSC arrangements should comply with the requirements set out in the PFMI implemented in the applicable domestic framework. Because GSC arrangements have many of the functions of cross-border and multi-currency payment and settlement systems, they have potential regulatory implications for multiple central banks. This is especially true if the arrangement is systemically important in multiple jurisdictions. PFMI's Responsibilities E address this situation by expecting the Central Bank and other relevant authorities to cooperate at the national and international levels, as appropriate, to improve the safety and efficiency of FMI.

Financial institutions and services

Financial institutions can provide many of the features associated with GSC. They may be custodians or wallet providers or traders/market makers. Some activities can be enforced by financial institutions with domestic and international standards. For example, new and existing hosted or custody wallet service providers will be subject to FATF standards (Recommendation 15) and state enforcement restrictions, especially from cryptoassets Fiat transfer currency.

The Basel Committee on Banking Supervision has made cautious expectations regarding the bank's exposure to cryptographic assets and related services. At the very least, banks are expected to conduct comprehensive due diligence before such activities, have a clear and robust risk management framework, disclose any material exposure or related services, and inform their actual or planned activities of regulatory authority (BCBS) (2019)).

For new entities, the associated risks and the identification of relevant regulatory agencies may be more complex, but there will be legal tools available to the competent authorities to respond. For example, a reserve pool can be considered a collective investment vehicle. This will place some specific requirements on unit disclosure and sale or leverage restrictions/restrictions in the reserve pool. Similarly, new tokens can be classified as securities, or as electronic money, each of which will be given rise to additional requirements in different jurisdictions (Zetzsche et al. (2019)).

Stock market