Why did Azuki’s Elementals collide in the release?

Why did Azuki's Elementals clash during the release?Authors: Jaleel, Jack, Block Rhythm

As the NFT market enters a bear market, even the market leader “Bored Ape” has not been able to escape, in stark contrast, Azuki has performed well. In the past three months, Azuki has gone against the market trend and successfully risen to become the strongest blue-chip project. Azuki, which had a floor price of over 30 ETH during the bull market peak, even rose to 17 ETH a few days ago. Moreover, the Azuki community has a rare community atmosphere and is extremely active and cohesive even in a bear market.

Until the release of Elements in the early hours of this morning, the community had broken its defense. In addition to the ten-minute window for the whitelist Mint period, which resulted in the website being overloaded and crashing in a short period of time. After the sale ended, the project team directly transferred 20,000 ETH. The most discussed topic in the community is the high degree of overlap between Elements and Azuki’s first generation, which may directly dilute the value of Azuki’s first generation.

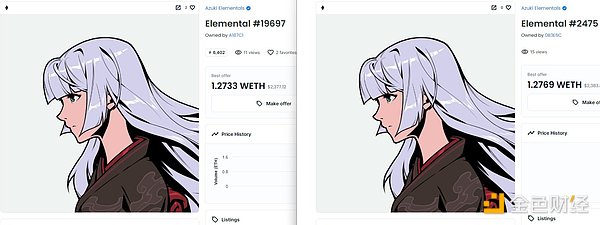

Initially, the community questioned the high degree of overlap between Elements and Azuki, but as more and more Elements were opened, many holders found that their Elements looked exactly the same as those of other holders, not just highly overlapping, but exactly the same.

- Goodbye Fork Swap, Uniswap V4 Enters the Era of “Ten Thousand Hooks”

- LD Capital: MakerDAO Status Update

- Evening Must-Read | Cancun Upgrade is Coming Soon, Reviewing Key Milestones in Ethereum’s History

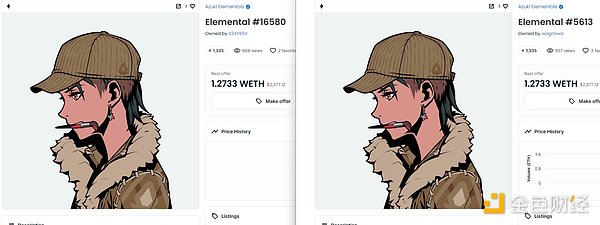

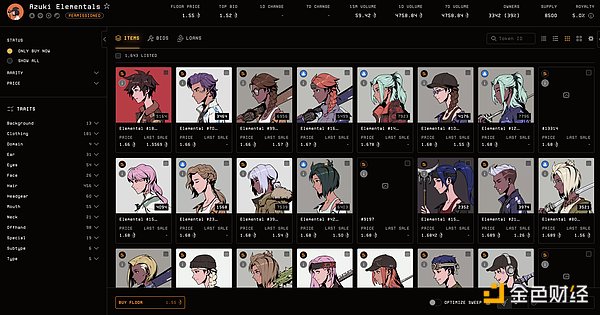

So far, five sets of completely identical pictures have been found for Elements. The numbers for these five sets are: #2210 and #10744; #1077 and #8600; #16046 and #8914; #16580 and #5613; #19697 and #2475. Not only are the NFTs of Elements displayed with exactly the same front-end pictures, but the pictures are even named the same when saved.

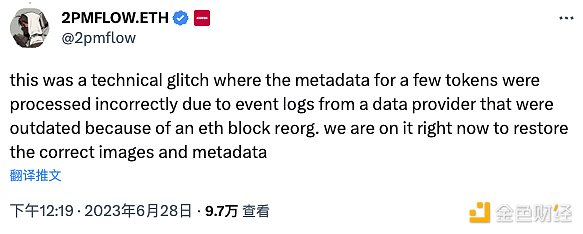

As more and more cases of image collisions were discovered during the opening of Elementals, the team realized the problem and responded. 2PMFLOW, co-founder of Azuki, replied to the community on social media, saying that this situation is a technical issue, caused by outdated event logs from data providers due to Ethereum blockchain reorganization, resulting in incorrect processing of metadata for a few tokens. The team is working hard to restore the correct images and metadata.

“Blockchain reorganization” occurs when blocks are produced simultaneously on the blockchain, and if errors or malicious attacks occur, temporary duplicate blockchains will be created. Because the miner who adds to the next block must decide which side of the fork is the correct or canonical chain, “blockchain reorganization” occurs. Once the miner chooses the fork or canonical chain, the other chain is lost.

The last major “blockchain reorganization” occurred on May 25, 2023. The Ethereum Beacon Chain experienced a seven-block reorganization, exposing a high-level security risk known as a chain reorganization. Validators on the Eth2 (now consensus layer upgrade) Beacon Chain became out of sync after upgrading a specific client.

“Collisions” are not actually rare

In response to Azuki co-founder 2PMFLOW’s statement that the collision was caused by a technical failure due to the Ethereum block reorganization, scriptmoney.lens, founder of cryptochasersco (@scriptdotmoney), disagrees and expressed his opinion on social media: The reason for the collision is that the server-side listener event did not handle the exception well, not the data provider. In other words, Azuki’s statement that the collision situation is a technical failure seems inconsistent.

When discussing the technical principles of NFT image generation, we need to focus on three core elements: layer style, generation algorithm, and the upload form of the generated NFT image. Due to the variability of these three factors, countless forms of NFT can be produced.

First of all, the layer can be viewed as a pre-made material, such as: 10 different colored backgrounds, 10 different hairstyles, 10 different hats, 10 different hand-held parts, etc., they are all independent layers. Once the number and style of layers are determined, we can preset various influencing factors such as the rarity index and the number of target-generated images, thereby creating a set of NFT algorithms that can generate various combinations. Then, according to the generation algorithm, each material layer is stacked from the bottom to the top to form a complete NFT.

Depending on the number of layers and the complexity of the algorithm prepared by the project party in advance, the probability of collisions in the generated NFTs is not the same. For example, if an NFT project party only prepares 3 layers, each layer has only more than 10 elements, and the generation algorithm is relatively simple, then the probability of collision in the NFT series will be very high. However, for blue-chip projects like Azuki, which have multiple layers, hundreds of elements, and extremely complex generation algorithms, even if tens of thousands of new NFTs are generated, it is difficult to collide.

Of course, since the process of generating images is done off-chain, even if there is a collision of images, it can be screened again before the image is officially put on the chain to filter out duplicate images. This requires the project party to fully screen the generated NFT images before putting them on the chain. Even if the project party directly uses the generated situation of the original materials, there should be a reasonable screening process to ensure the performance of the program and that all combinations strictly follow the preset probability distribution.

So, what is the problem with Elementals?

First of all, it is most obvious that Elements may directly use Azuki or BeanZ’s layers, elements, or even generation algorithms. However, perhaps because the NFT series is centered around limited “element concepts” such as water, fire, and electricity, the relevant generation algorithm was not debugged properly, resulting in the occurrence of duplicate NFT generation.

Secondly, the community’s statement that “the same picture is minted in the same block” does not seem to be completely true. According to an NFT technician, the NFTs in the Elementals series that appeared to be collided did not have a similar or consecutive sequence, indicating that the probability of their being minted in the same block was small. Therefore, another explanation is that the Azuki team did not screen the generated Elementals again, resulting in duplicate images being directly transferred to the chain.

Of course, no matter what the reason is, it is unacceptable for blue-chip NFT project parties like Azuki to have image collision incidents. Obviously, the team did not make sufficient preparations before the release of Elementals.

Why can the pictures on the chain be modified when changing pictures in front of your eyes?

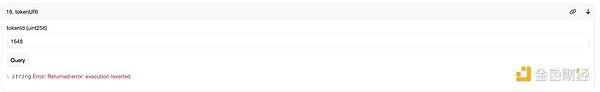

Regarding the problem of Elementals casting and opening pictures, 2PMFLOW, co-founder of Azuki, responded to the community on social media that the team is working hard to restore the correct images and metadata for Elementals. Later, BlockBeats also found that when querying the Elementals series contract, some NFT’s tokenURL could not display query results. At the same time, part of the NFT preview pictures in the Elementals series cannot be displayed normally on Blur and other NFT trading platforms. Azuki team thus conducted a real-time “live replacement of pictures” in front of the community.

Once an NFT has been uploaded to the blockchain and minted, why is it still possible to change or modify it? This requires a simple review of how NFT images are stored.

As we know, today’s internet is built on the HTTP protocol, which is used to transfer hypertext from network servers to local browsers. When we retrieve a webpage or file via HTTP, we request and receive the information from a server. This is a centralized process that has multiple issues, such as the file becoming inaccessible if the server experiences a failure, and if large numbers of users attempt to access the same file simultaneously, it can put great pressure on the server’s bandwidth.

In contrast, IPFS employs a more distributed approach. IPFS is a protocol and network designed to create persistent and distributed storage and sharing of files, and is a new hypermedia transfer protocol that addresses a large number of data storage and bandwidth issues. IPFS stores files and other data as blocks across multiple nodes, and uses unique hash values to identify each block. When a user requests a file, IPFS retrieves the blocks from the nearest node, rather than from the original server. This makes accessing data faster and more stable, and prevents data from becoming inaccessible due to a single server failure.

Due to these advantages, IPFS has become the ideal choice and consensus for storing NFT metadata today. NFTs typically contain information such as descriptions of artwork, such as the author and creation date, and this information is known as metadata. Because NFTs are immutable, metadata needs to be permanently stored, and IPFS’s distributed nature can provide this service. Additionally, IPFS’s distributed nature can prevent NFT metadata from being tampered with, ensuring the security of the NFT.

In IPFS’s file system, each file will generate a hash value based on its content, and the file in IPFS will be indexed based on this hash value. The hash value will be pre-checked to see if it has already been stored. If it has been stored, it will be read directly from another node, without the need for redundant storage, which saves space to some extent. This greatly improves the efficiency of resource storage and reduces transaction costs.

However, after querying the contract of the Elementals series, we found that the image metadata of Elementals has not been uploaded to IPFS, but is stored in Azuki’s own centralized server. Therefore, the ownership and modification rights of the metadata are held by the Azuki team and can be changed at any time.

Actually, it’s not just Elementals that chooses to store images on its own server. Many “rich” blue-chip NFTs do the same to gain greater control over the project. However, compared to Elementals, the metadata for the previous Azuki series was stored on IPFS. So why did the team “reverse” the decentralization process for the project? Perhaps everyone realized from the beginning that Elementals might be in trouble.

What’s even more outrageous is that the team made new mistakes during the metadata modification process. Scriptmoney.lens also found that the fix metadata uploaded by the Azuki team seems to be a file, so it jumps to the download page as soon as it is accessed. That is to say, the server did not upload the normal json meta code, but directly uploaded the image file. Therefore, when third-party trading platforms like Blur look for NFT image data on the server, they cannot read it properly, resulting in the problem presented at the beginning of this paragraph.

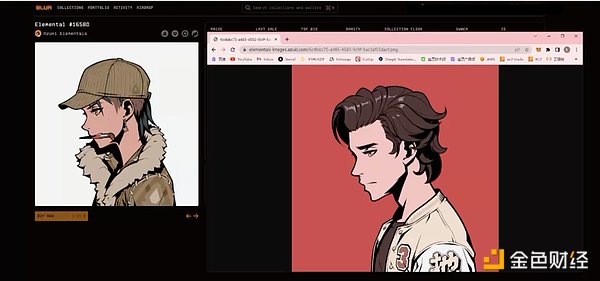

When we look at the downloaded files pointed to by the metadata, we find that these new images can’t even be described as “fixed”. Taking Elementals #16580 as an example, as of the writing of this article, the metadata file for this NFT is not the same as the original in any way (see the figure below). Although the team had previously announced its image replacement action, such a big difference may be difficult for many people to accept.

From whatever angle we evaluate it, the release of Elementals is a disastrous event. It not only hits the Azuki community itself, but also the entire avatar NFT field. From experience, people’s confidence and trust in NFT project parties are often very fragile, and Azuki’s vampire behavior is rapidly consuming the only remaining faith in this industry.

Of course, in the face of community questioning and criticism, the Azuki team has also responded positively, saying that it will work hard to make up for its mistakes, and announced a new “green bean” airdrop this afternoon. Although the scene of Elementals is very chaotic, perhaps we can leave some faith and give the Azuki team one last chance?

We will continue to update Blocking; if you have any questions or suggestions, please contact us!

Was this article helpful?

93 out of 132 found this helpful

Related articles

- Is the surge in zkSync Era on-chain data a bubble or a real ecosystem?

- As the staking rewards for Ether decrease, the protocol will have to seek innovative solutions.

- Exclusive new research on SUI: Distorted emissions? Dumping of non-tradable tokens?

- How to empower infrastructure and serve billions of users through account abstraction?

- Reflections One Month After Montenegro EDCON 2023: Forward-looking Trends in Infrastructure and Applications

- Can you earn money by running a node? How to choose a public chain? We talked to a node operator about it.

- Interpreting the Narrative of HOPE’s Resurrection