Can the United States really avoid a recession?

Can the US avoid a recession?Article Author: JOSEPH POLITANO

Article Translation: Block unicorn

- Blocking Daily | OpenAI releases iOS version of ChatGPT app; Hashkey Group plans to raise $100 million to $200 million in funding with a valuation of over $1 billion

- Why did hardware wallet Ledger launch the Ledger Recover service, which has sparked criticism from the Web3 community?

- 3 Counterintuitive Experiences in Cryptocurrency Investment

Despite being positive, actual growth has been weak, while inflation is slowly decelerating. Can the United States truly avoid an economic recession?

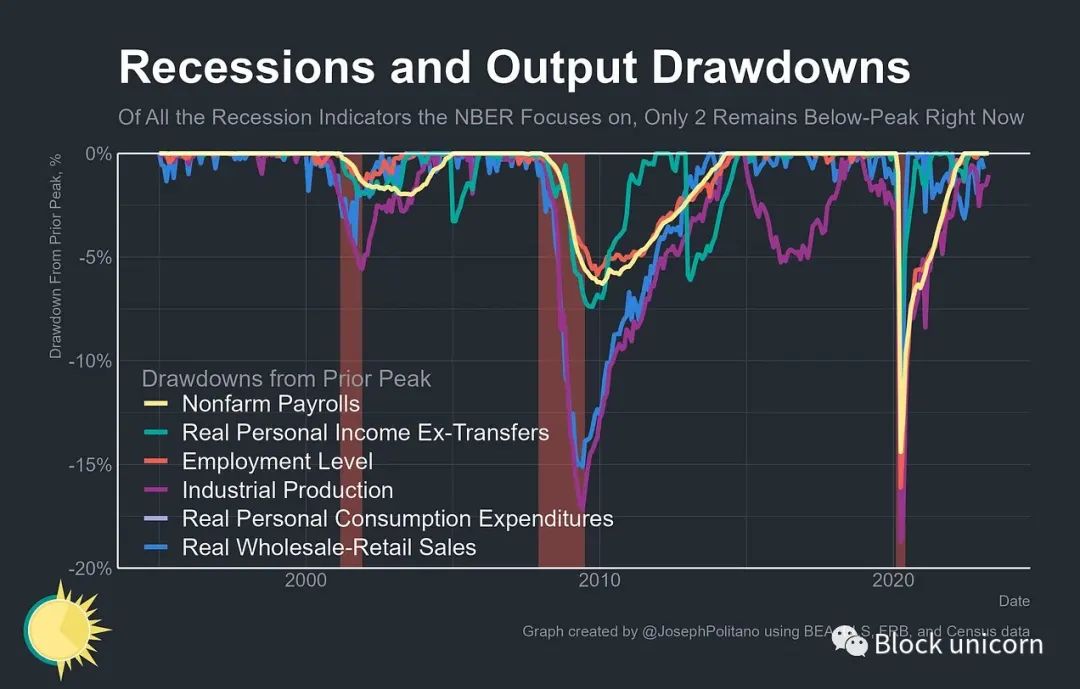

Since the Federal Reserve began raising rates early in 2022, the US economy has slowed significantly – actual growth has declined, largely due to a drop in fixed investment, and nominal expenditure growth has also dropped significantly. However, we are still far from an official announcement of an economic recession – only two (industrial output and actual retail-wholesale sales) of the six indicators watched by the National Bureau of Economic Research’s recession dating committee are still below their previous peak levels. At the same time, inflation and nominal growth have been declining for several months in a row. This is partly why Federal Reserve officials have shown a glimmer of optimism despite the recent banking crisis. The Federal Reserve no longer believes “additional policy tightening is needed,” although there is still room to raise rates further if economic data proves strong. Jerome Powell said, “In my view, the possibility of avoiding an economic recession is greater than the possibility of an economic recession occurring,” which contrasts with recent Federal Reserve predictions that the unemployment rate will rise rapidly and enter a recession phase in 2023.

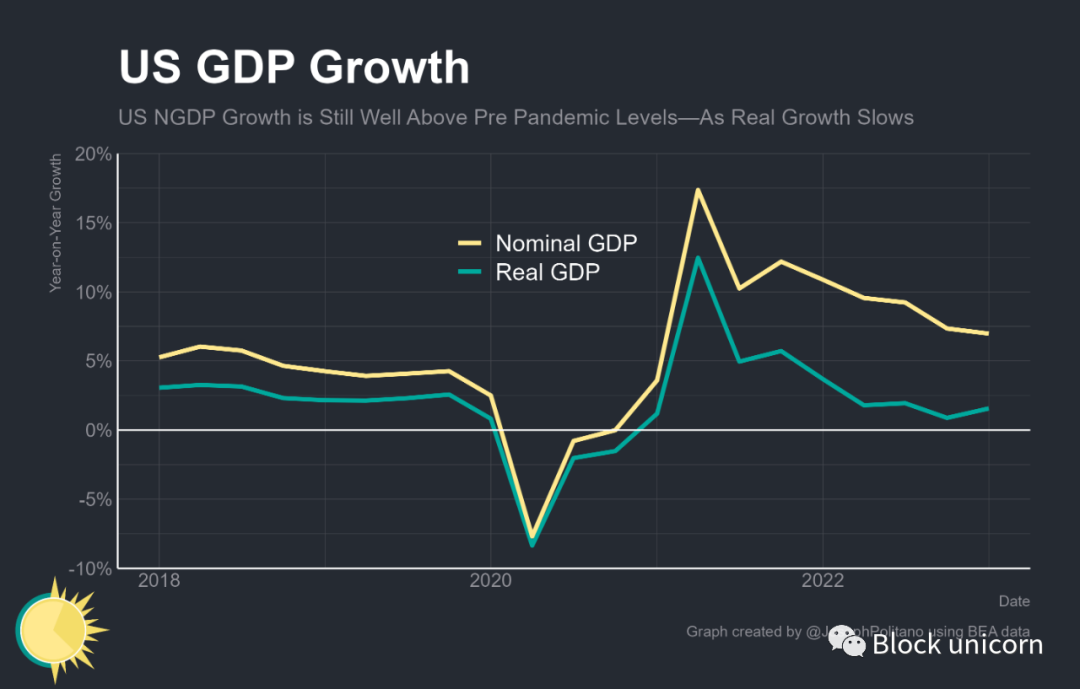

However, the economy is still too strong, exceeding the Federal Reserve’s preferences – the reason for pausing the rate hike depends on the “cumulative tightening of monetary policy” and the “lag effect of monetary policy on economic activity and inflation” being sufficient to further depress nominal economic growth and future inflation. This cumulative tightening is also not enough to push the US economy into a recession – since 2022, although actual growth has been positive, it has been weak. In the past year, nominal gross domestic product (NGDP, the dollar size of the US economy) has grown by nearly 7%, but inflation-adjusted growth has only been 1.6%.

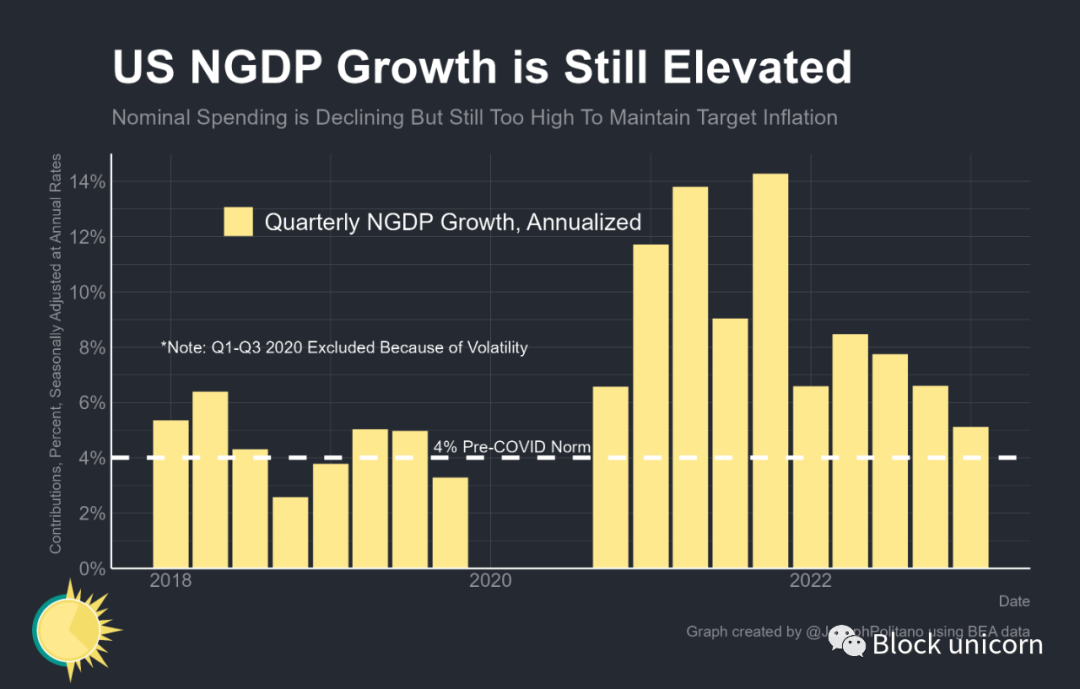

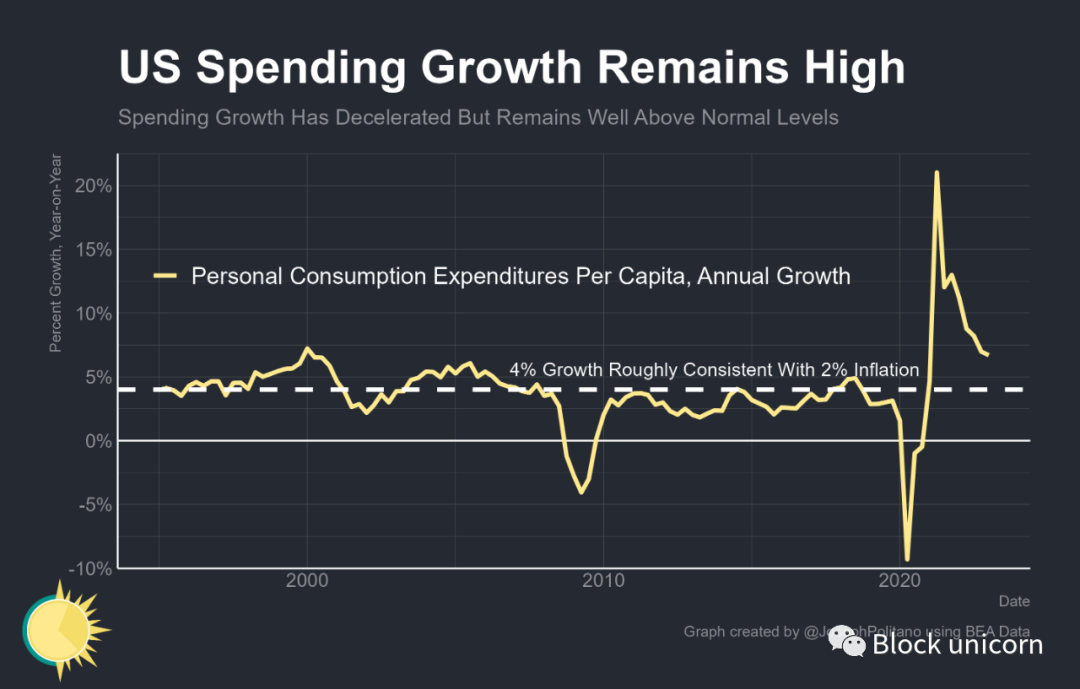

However, nominal GDP growth has significantly slowed in 2022, with first quarter growth reaching its lowest level since the pandemic began. It is still too high to be comfortable – an annualized 5% compared to a 2% inflation rate and a level of about 4% that is consistent with pre-pandemic normality, and projects such as consumer spending are still growing faster than overall growth – but it has made significant progress towards the target level without the start of unemployment or recession.

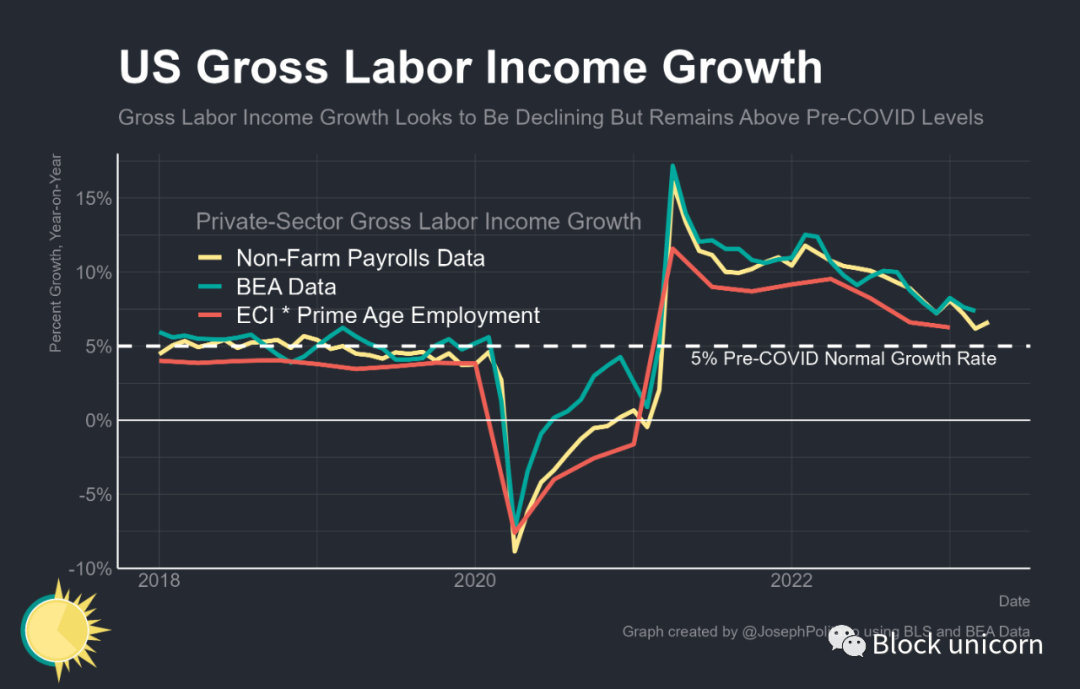

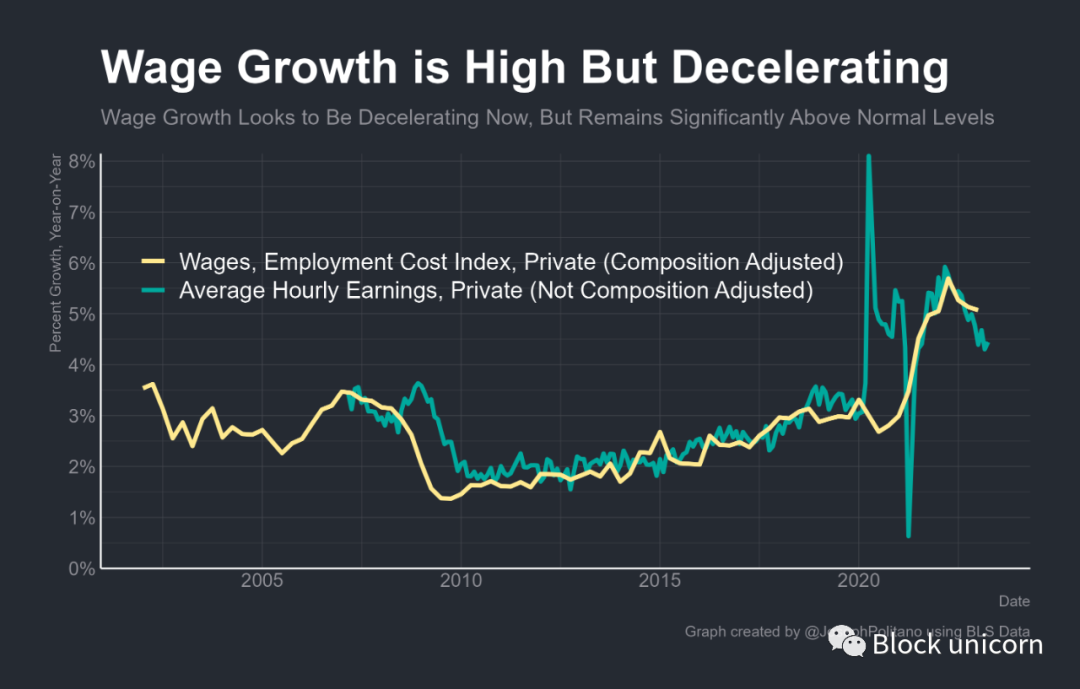

The growth of gross labor income (GLI), or the total income of all workers in the economy, continues to slow down and approach normal levels similar to pre-pandemic levels. Whether from strong real-time measures derived from employment cost indices and household employment levels, or from more frequent non-agricultural wage data, the past year’s GLI growth has only been 6.2% and 6.6% (compared to about 5% pre-pandemic normalcy). For the Federal Reserve System, which is now primarily concerned about the impact of inflation on core services, the normalization of GLI growth should be a welcome sign of slowing house prices and labor-intensive non-housing service prices.

Overall, we still see some cyclical nominal growth slowdowns that are necessary to reach inflation targets – but not all that is needed has been achieved, and the time it will take the Federal Reserve System to achieve its goals will be longer if underlying economic data continues to be strong. However, similarly, longer and more stable cooling may maximize the possibility of minimizing the kind of rapid economic collapse that people have been most concerned about since the Federal Reserve System began tightening policy last year. So far, the economy has proven to be more resilient to rising interest rates than previously expected – which has also extended the timeline for repairing inflation while reducing the likelihood of a recession, although that likelihood remains high.

The Real Strength of the United States

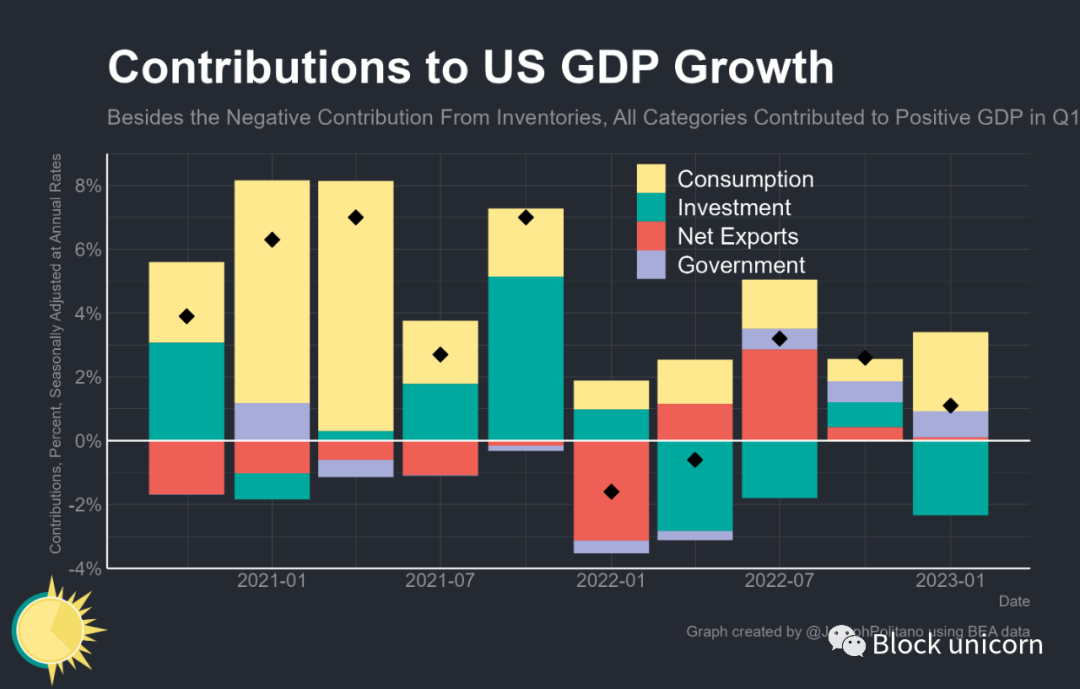

After a year that saw fears of a recession sparked by two consecutive quarters of negative GDP growth, the US has now seen three consecutive quarters of actual growth. The low but positive numbers for Q1 were stronger than they initially appeared — consumption, government spending, and net exports all contributed to overall growth, with the main drag coming from a sharp decline in investment. However, actual fixed investment (such as housing construction, factory construction, and R&D) only slipped slightly, and the main driver of investment weakness was a deceleration in the volatile growth of business inventories.

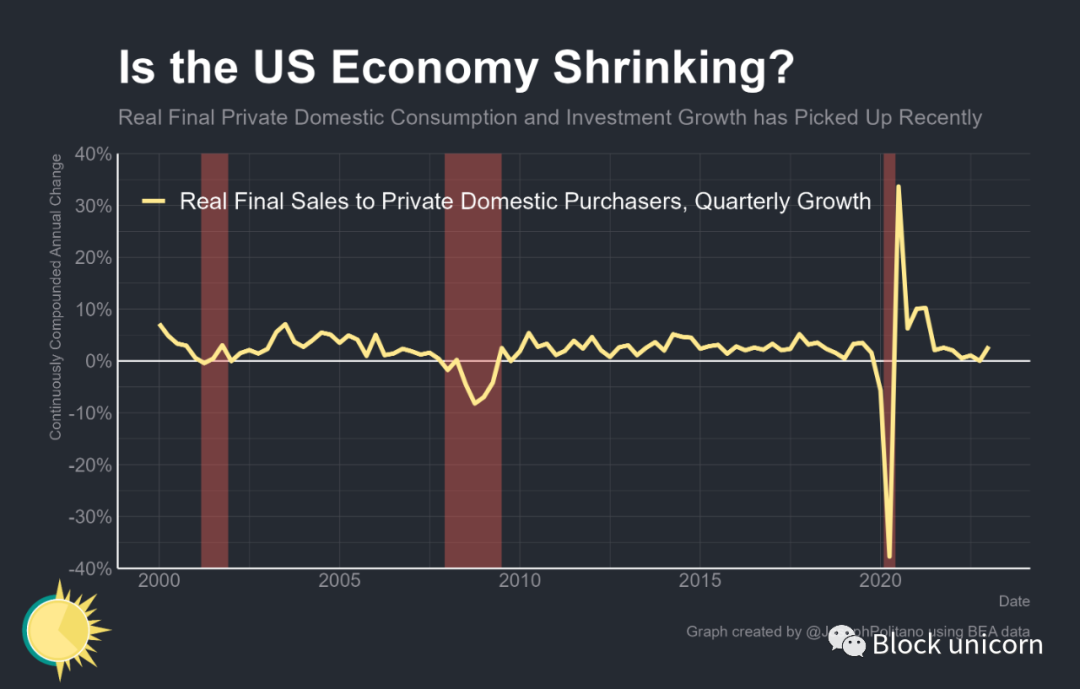

In fact, real final sales to private domestic purchasers, a niche indicator that reflects growth in private sector consumption and fixed investment, rebounded slightly in Q1 after almost no growth in the past three quarters. Given the importance of this indicator as a proxy for core economic growth — it rarely shows negative growth in a quarter outside of a recession — this is another sign that the underlying US economy has yet to begin shrinking.

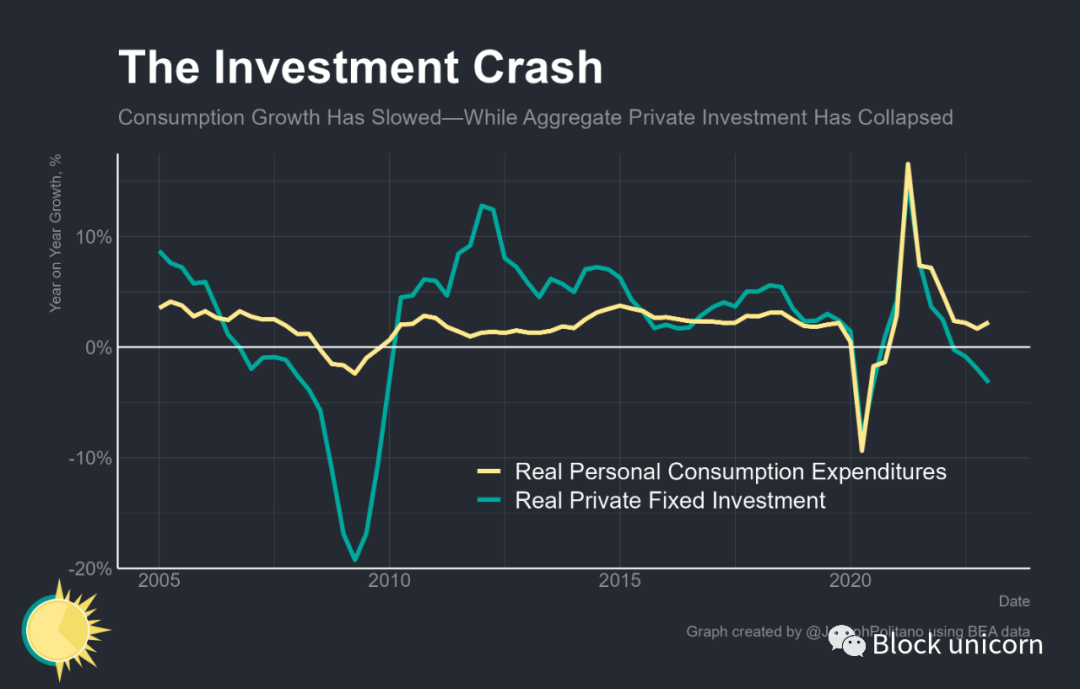

The recent rebound has been driven mainly by the recovery in actual consumption, even as nominal consumption is slowing — reflecting, to some extent, improvements in supply and production chains. About one-sixth of the increase in Q1 consumption spending reflects growth in spending on cars and car parts as the auto supply chain continues to improve. In contrast to the ongoing decline in actual fixed investment, annual real consumption growth has rebounded from its low point in 2021.

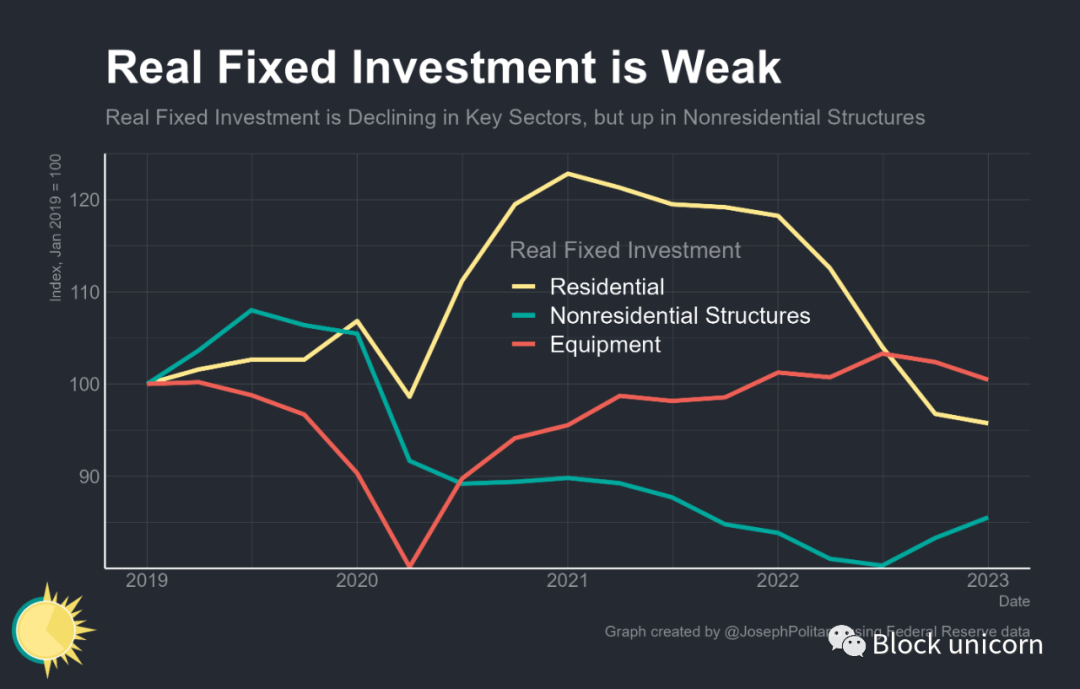

Although residential fixed investment has now fallen to its lowest level in seven years, it appears to be finally stabilizing as mortgage interest rates remain steady. Single-family housing starts have remained around 840k per year since last October, while multi-family housing starts have remained around 540k per year. Non-residential fixed investment has slowed but not declined, thanks to relatively strong manufacturing investment in the wake of the Chip Act and the Inflation Reduction Act, as well as still-strong intellectual property and R&D spending.

In fact, actual fixed investment may be stronger than currently reported—the Census Bureau estimates nominal construction outlays for nonresponding projects based on initial budgets and assumes that nonresponding projects are complete once the imputed cost reaches 101.5% of the original estimate. Given that the rate of inflation for construction materials has been high, budgets for projects have consistently exceeded initial estimates, leading to upward revisions of Census Bureau data on nonresidential expenditures after previously imputed-as-complete projects are reported by firms. Researchers at the Federal Reserve System (Brandsaas, Garcia, Nichols, and Sadovi) estimate that a simple predictive model based on other actual nonresidential expenditure data suggests that the true value of nonresidential fixed investment may be 20% higher than currently reported. So fixed investment may be revised upward substantially during the recent period of inflation—further strengthening recent economic data.

Nominal Growth, Labor Market, and Inflation

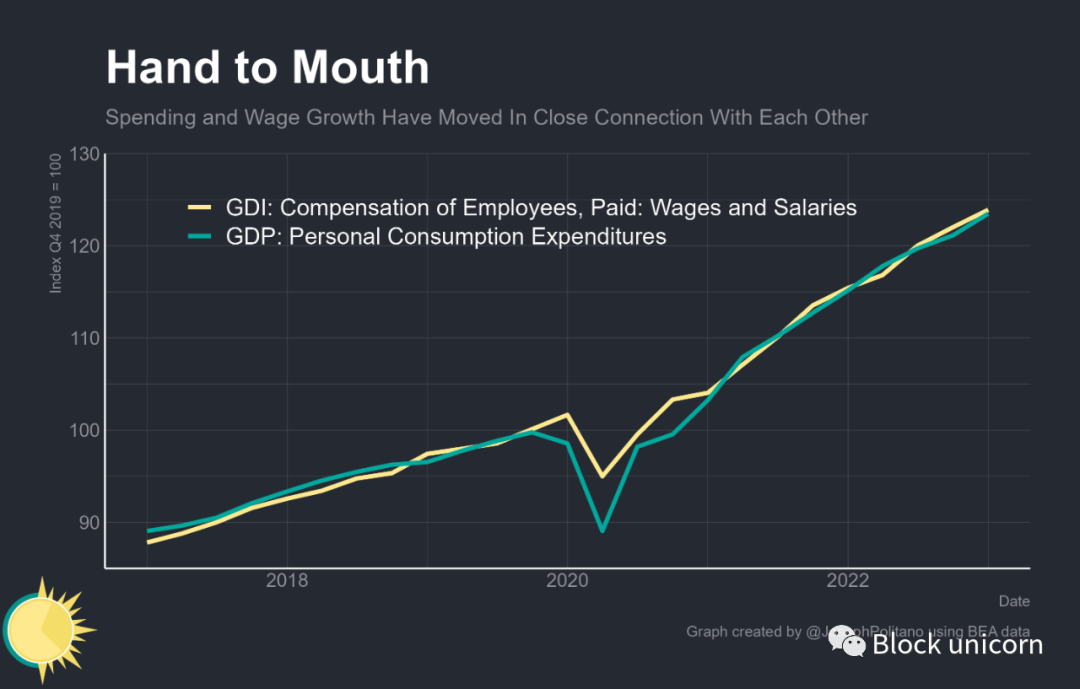

However, to bring inflation back to target levels, further slowing of the growth in total labor income is still needed. Despite the massive pandemic-era stimulus measures and shifts in borrowing behavior, as Matt Klein has repeatedly emphasized, nominal consumption expenditures have basically grown in lockstep with total wages since early 2021. Unsustainable high consumption growth is partly a function of rapidly rising household incomes, and slowing household incomes are still necessary to bring inflation back to the Federal Reserve System’s 2% trend.

However, over the past year, the labor market has also cooled significantly but has not entered recession territory. Average hourly wage growth has fallen from 6% to less than 4.5%, and the more robust composition-adjusted employment cost index has slipped from 5.7% to 5%, while the unemployment rate has not risen.

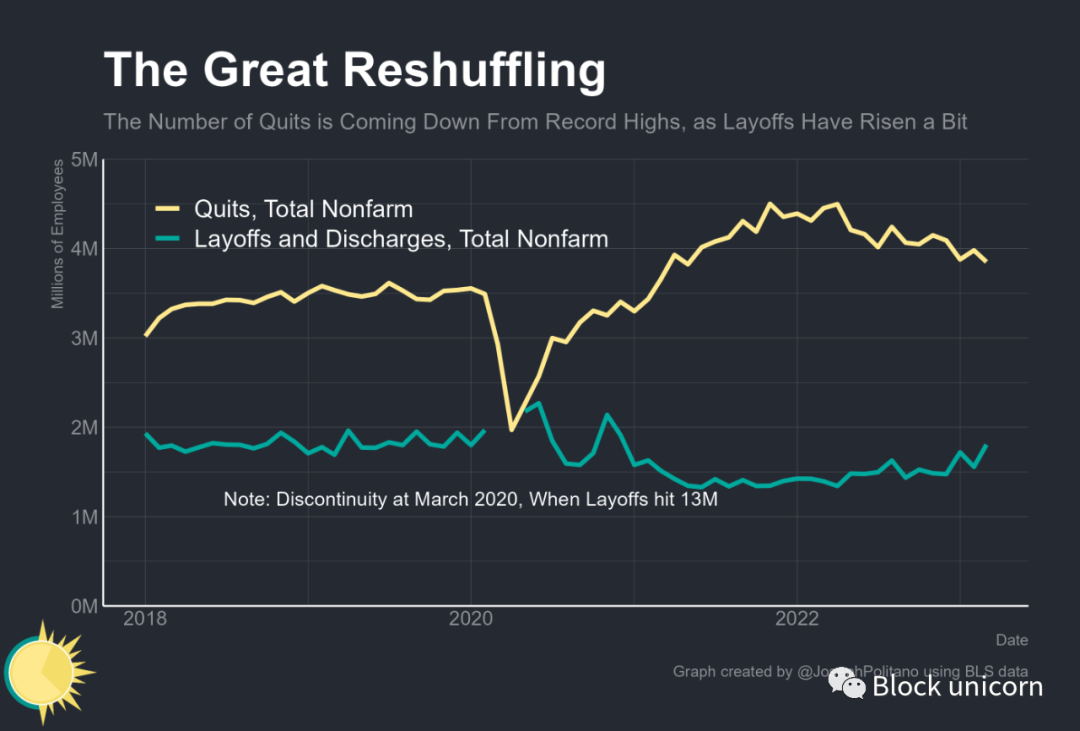

The leading indicators of a strong labor market and total labor income growth have also significantly weakened. The number of workers quitting each month has declined from a high of 4.5 million per month in early 2022 to 3.9 million per month currently, and the number of workers being laid off each month has increased to pre-pandemic levels in recent months. Continuing unemployment claims also remain elevated after a recent bounce back, closer to pre-pandemic averages.

All of this helps bring nominal spending growth down from the extremely high levels of 2021 and 2022 to more reasonable but still historically elevated levels. Per capita spending grew 6.7% over the past year, with quarterly growth at the beginning of this year actually rebounding. Further slowing of spending growth is needed to control inflation.

Conclusion

When the Federal Open Market Committee (FOMC) conducted its economic forecasts in March, the median participant expected the unemployment rate to reach 4.5% by year-end, slightly more optimistic than the December 2022 forecast of 4.6%. As time has gone on, these forecasts look increasingly unrealistic — reaching 4.5% by year-end would require a rise of over 0.1% each month. Assuming no change in the labor force, this would require sustained net job losses averaging about 200-250k per month, a pace only consistent with the most severe U.S. recessions.

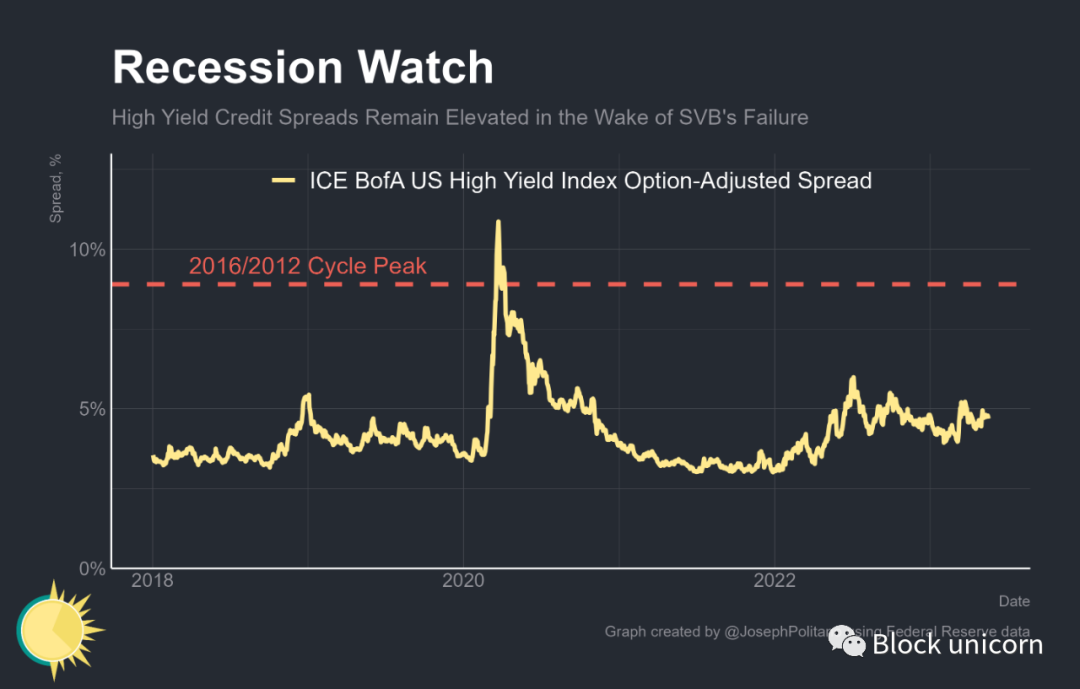

Yet the debt market is not pricing in a looming catastrophic downturn — high-yield corporate bond spreads, a proxy for large corporate default risk and therefore an important recession indicator, remain below their peak levels of 2022 despite a recent rise due to the collapse of Silicon Valley Bank and other regional U.S. banks.

At the next FOMC meeting, the most likely outcome is that participants will once again be forced to revise their forecasts — both by extending the time frame in which they expect to see economic contraction and by minimizing the expected magnitude of the contraction. The landing is getting longer and the hope softer.

Follow us on Twitter: @BlockUnicorn

If you like our content, you can mark Block unicorn with a star and add it to your desktop.

The information provided in this article is for general guidance and informational purposes only, and the contents of this article should not be construed as investment, business, legal or tax advice under any circumstances. We do not accept any responsibility for individual decisions made based on this article, and strongly recommend that you conduct your own research before taking any action. While every effort has been made to ensure that all information provided here is accurate and up-to-date, omissions or errors may occur.

We will continue to update Blocking; if you have any questions or suggestions, please contact us!

Was this article helpful?

93 out of 132 found this helpful

Related articles

- EigenLayer, which raised $64.5 million in financing: A new narrative in the collateralized track

- US SEC Chairman’s pessimistic tone: Cryptocurrency businesses often non-compliant, filled with opacity and risk

- What would happen to Bitcoin if the black swan of US debt occurs?

- Inventory of the top 5 Ethereum GAS consumers

- Future Development History of NFT Derivatives: From Commodity Speculation to Financial Speculation, Gradually Abstracted Asset Symbols

- Why did Ethereum have two brief outages in a row? An analysis of the causes of the incident.

- After the explosion, searching for the past of BRC-20