Echo | Vernacular Balance Sheet: What does it have to do with distributed ledgers?

Editor's Note: We suddenly had an idea lately. At the beginning of many articles, many articles inspired many people and became an opportunity for some friends to recognize breakthroughs. Today, it is still a good material for entry. Therefore, we hope to re-translate or re-publish some articles many years ago, and we will call it the “Echo” series. The echo that hits the ground.

The writer is CTO of R3, Richard Gendal Brown. In this article, he explains the balance sheet and the operation of the bank on the one hand, and puts forward a vision that we still seem to be very bold today. In general, we all want to record rough information on the public ledger, and record more detailed information on our private ledger for the simple reason that these details are the key to our ability to explore user habits and control the user's financial situation. . But Richard's idea is that perhaps the public ledger will be used to record more detailed information, and the private ledger itself will become lighter. – Although not necessarily realistic, it is really bold and enjoyable.

If your friend tells you that they have £1 million in the bank, what would your first reaction be? Congratulations on their good luck? Still a polite and unsmiling smile?

Xiongtai, this is not right!

- Early return on investment is up to 2000 times! Blockstack officially applied for US$50 million in token sales to the US SEC

- Twitter annual drama! Encryption community

- After the new SEC regulations, the cryptocurrency change geometry?

Your first reaction is to tell them loudly: "The silly son of the landlord's house! Not that you have one million in the bank, but you lend the bank one million, and then they owe you one million. You are in the banking industry. Nothing to know!"

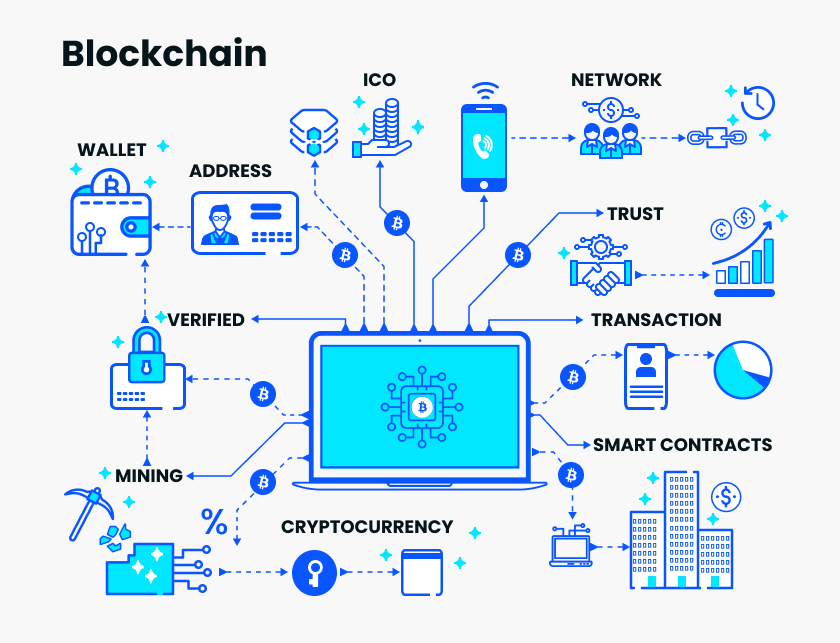

If your first reaction is correct, then you don't have to look down. You already know what you are going to say in this article. However, for others, if you don't read this article, you may miss something very important. As I have mentioned repeatedly: we can witness the emergence of shared ledgers (blockchains) in the financial sector. In the future, blockchains will be used to record obligations and agreements between companies and different users. For example, it might be like this:

– Share the four columns of data in the ledger model. –

To understand the potential of shared ledgers, we must have a more accurate understanding of financial relationships. And I am pretty sure, first you have to understand the balance sheet.

What is a balance sheet?

Suppose you want to open a bank. You want to build a system that records your financial situation: How much cash is in your vault? How much do you owe? How much do you borrow? and many more.

In fact, the basic content is not complicated, as long as there are two key reports: balance sheet and income statement (ie, P+L)

They answered two important questions:

- The balance sheet can tell you: What assets do you hold? And, how much is your debt? You can think of it as a snapshot at some point in time.

- So what was my revenue in the last period? This is what the income statement should record, and you can think of it as a detailed record of how much revenue you got from last year to this year.

In this article, we will study the balance sheet. I think if you want to understand the direction of the shared ledger, then you must understand the balance sheet.

The good news is that the balance sheet is simple… it has only two columns:

- You write everything you have (your assets) in one column.

- You write everything you owe (your debt) to another column.

- If your assets are greater than the liabilities, then the difference belongs to your shareholders: their “equity” (owner's equity) adds the debt to the owner's equity and the asset “balanced” (equal). (Translator's Note: total assets = total liabilities + owner's equity)

- If your debt is greater than the assets, then you are bankrupt ("insolvency"):

– A balance sheet has only two important columns: assets and liabilities –

Let us open a bank!

Now let us imagine that you are ready to open a small bank "GendalBank". Your friends think that investing in your bank is a good deal, so they agree to invest £1 million to get the bank up and running. They also obtained shares in the bank.

You said that 1 million can't open a bank? Well, don't care about those details…

One thing may be obvious, but I must say: these shareholders have no right to ask the bank for a refund… The money they invest in the bank is not a loan. However, if you close the company, after you pay off all the employees, suppliers, lending institutions, etc., everything left will belong to the shareholders.

Therefore, what they really hold is the ownership of the company's remaining assets . This is the owner's equity. Looking at it from this perspective, it is clear that the owner's equity is a (special) liability of the company : if GendalBank closes, it is obliged to return the remaining assets to shareholders.

In this way, GendalBank was formed and shareholders invested £1 million. So at this time, how do we prepare a balance sheet to reflect the current relationship between assets and liabilities?

– After shareholders buy their shares, GendalBank's balance sheet will be as shown above. (Insert: Please forgive me… I omitted the single quotes in "Shareholders' funds". It takes too much time to modify the information in the 10 tables… But I can assure you that I am also very comfortable. )

This is exactly what we expect. Your new bank has £1 million in cash – you might put it in a vault or in the Bank of England. But in any case, this cash is now belonging to GendalBank … It is no longer a shareholder, but a company, now a bank 's assets. Banks can use this cash to do whatever they want. So let's put it in the asset column.

Remember, shareholders buy ownership of the company's remaining assets. Since the company currently has no other debt, we recorded a £1 million liability to shareholders. If we close the company now, they will be entitled to get this £1 million.

Need to reiterate: bank capital is a liability . This is a very useful knowledge. Because it allows you to see a liar at a glance… Whenever you hear someone talking about capital as a bank's assets (or "holding capital"), you understand that they don't know what they are talking about… …

Very good… Now we can use the money to buy some IT equipment and an office. Maybe the balance sheet would be like this at the end of the first week:

– We use part of the cash to buy equipment and offices. –

For the sake of simplicity, I assume that the bank has no expenses. This is done to highlight the point. So we assume that we have an office, but we don't have to pay employees (avoid the content of the income statement).

Now that we are open… It’s time to let the loan go…

Bob walked in from the street and offered to borrow £100,000 because he planned to buy a very good car on the weekend. He seems to be a trustworthy person, so we lend it to him.

Another interesting thing happened next: we made money out of thin air…

– We made money out of thin air and loaned it to Bob –

Bob hasn't got the money yet – remember, he won't buy a car until the weekend. But looking at the balance sheet seems to be a bit confusing.

Let's first look at the asset side: we still hold £500,000 in cash. That's of course, because Bob hasn't taken money yet. Then we saw the £100,000 loan to Bob. This loan is also our asset, because Bob must pay us £100,000 in the coming months or years. What is certain is that this is a valuable commitment – and therefore an asset to the bank.

Interspersed: As above, I have done a lot of simplification here, especially since I completely ignore the factors such as interest rate and discount rate.

Now look at the debt column: it records that we owe Bob 100,000 pounds. This is fair. If he looks at the account, he will be able to see that he can withdraw £100,000 at any time. For him, he would think “I have £100,000 in the bank”.

Therefore, we have £500,000 in cash (whether in the vault or in the Bank of England). Bob also believes he has a £100,000 “bank deposit”.

So what is going on here? Are we getting 100,000 pounds more by moving our fingers? Or is it actually that 100,000 of the £500,000 should be counted as Bob? still is……?

The way to understand this is to observe that £500,000 is our asset and £100,000 is Bob 's assets (ie, our liabilities ). They are not the same thing at all, and comparing them in this way is meaningless.

So this is another way to find a liar: if you hear someone talking about bank deposits as a bank's assets , you can safely ignore what the person said… as this example shows, our bank deposits It's the bank's debt … and you have to pay attention to the bank's debt, because the user's habits are very uncertain, they may ask you to pay the money in the bank at any time to let him spend. To ensure this kind of immediate solvency, you have to make sure that the bank has enough cash (cash is in the asset column).

This is what people mean when discussing “liquidity” – do you have enough cash or (capable of realizing) capital to meet your customers' withdrawal requests?

Interspersed: From multiple perspectives, this issue is the absolute core of the banking industry: how to manage the issuance of short-term liabilities (for example, demand deposits) while holding longer-term assets (for example, one-year auto loans). This question even has a unique name: maturity conversion. It obviously depends on not all “depositors” wanting to take out “they” deposits at the same time, so the underlying assumption of this question is unstable (proofing note: it can be simply understood as a run-through problem).

But it turns out that we have enough cash on hand. So we lived another day.

Further, we can release a lot of loans . As long as not everyone wants to withdraw money immediately, maybe our bank will be able to function properly. Let's imagine that many other customers plan to buy large items in the future and borrow some money from us. The following is the way we provide the balance sheet after the loan, at which point the customer of the loan has not yet withdrawn any cash.

– We have provided a lot of loans, making the balance sheet bigger and bigger…-

However, borrowing money always has to be spent. If someone wants to take out the money to spend, will there be any problems?

This kind of request may be okay, at least we have a little home, we have a part of the cash, we can also lend to other banks. Suppose the customer asks to withdraw 5 million from the loan, and we don't actually have £5 million in cash… But that's okay… Suppose we are not bankrupt, we have solvency, and others believe we have solvency, maybe we can Temporarily borrow money from other people (for example, the central bank).

The solution is as follows:

– We borrowed £5 million from other locations for cash depositors who want to withdraw cash. Note that the “deposits” in the liability column were reduced by £5 million, while the liabilities to other banks increased by £5 million. The asset column of the balance sheet does not change in this example.

Of course, another thing we can do is to sell part of the loan (debt) to someone else in exchange for cash. This will also reduce the size of the balance sheet… After doing so, we have only £5 million in loans in the asset column.

But this is really weird, isn't it? We set up a bank that provides a lot of loans, but we have n't even received a deposit!

In fact, there are even more strange places… We have created deposits out of thin air by providing loans. After all, besides the loan we provided him, where can Bob's “deposit” come from? It turns out that this is very important. The Bank of England also believes that this mechanism is the main way to create money in the modern economy. What you learned at school about the need for deposits by banks to make loans is not really true… But we will discuss this topic later…

"deposit"

I have written an article explaining how the payment system works. My influence is very shocking: the article has received hundreds of thousands of hits, and most of the readers are bank workers. Obviously: the truth is not seen at a glance.

One of the key points I mentioned in that article is a point I hinted at earlier: It doesn't make sense to say that you “pay for the bank” or that you “have money in the bank”. There is no jar in the back of the bank to hold your money, and you will not write your name on the safe. Instead, when you “deposit” to the bank, what you are actually doing is lending the money to the bank . These cash is no longer yours , they become the assets of the bank . As they expected, the assets that belonged to you became their assets . In exchange, they promise you that if you have a need, they will give you cash. You have obtained a claim against the bank.

So, if someone deposits, what will happen to the balance sheet?

Let's imagine that Alice has just sold her house for £500,000 and needs somewhere to store her cash:

– Since Alice has stored £500,000 in cash at our bank, we have an additional £500,000 in cash on hand –

So the balance sheet is as we expected: we recorded the fact that we owe Alice £500,000 (our debt) and added an additional £500,000 in our vault (or in the Bank of England) (our assets).

What is the relationship between the balance sheet and the distributed ledger? !

It is already very good to be able to see it here. Then why do I have to write these things? Because, as I pointed out recently, we may enter a world where agreements and obligations between companies are recorded on a shared book at an industry or market level, rather than on privately maintained by a single entity. On the system.

Moreover, if such a system becomes a reality, we must first understand the essence of deposits and loans. Only when everyone building this system has a deep and intuitive understanding that “deposits” should be modeled as “claims for identifiable entities”, GendalBank’s £500,000 is essentially different from OtherBank’s £500,000. The system will appear. I think we need to consider the "four-column model" of "Issuer", "Holder", "Asset", and "Value".

– Will the "four-column" model be the core data structure of the shared book world? (This is not my original: this concept is the core concept of blockchain systems such as Ripple, Stellar, Hyperledger) –

Perhaps more importantly, once you start thinking about it like this, you may see the future.

Imagine a world where the bank still records some of the money it owes its customers, but the shared ledger will accurately record who these people are. This is fundamentally different from using a shared ledger as a mirror (or mapping a shared ledger to the bank's own ledger), which is more similar to treating a shared ledger as a partial sub-book .

And the acceptance (degree of use) of each company will vary.

Maybe GendalBank only uses a shared ledger to record certain balances. So we updated the GendalBank system to indicate that it owes someone £5 million, but the distributed ledger records who the £5 million owed by GendalBank is. From the table on the distributed ledger above, we see that the £5 million is from Charlie and Debbie. As a result, the £5 million was recorded in two places (balance sheet and shared ledger), but the shared book has a finer granularity of records. Therefore, the shared ledger becomes a sub-book of certain deposits ("DistLedger" below), and the bank's own ledger is used to record other facts.

– Maybe GendalBank only uses the shared ledger to record the details of certain accounts ("DistLedger") and continue to maintain other information locally –

Instead, OtherBank may go a step further and port everything to the distributed ledger (all balance sheets). Therefore, OtherBank's internal ledger is very simple: it only records the value of assets and liabilities outside the shared ledger:

– OtherBank has "outsourced" or migrated all transactions to a shared ledger –

So?

Let's take a look at the shared ledger:

Suppose you are Charlie. If you have the ability to read/write this shared ledger, you can sell your claim to GendalBank to any other user using the ledger without going through the GendalBank system. We have decoupled deposit and loan functions from record keeping, accounting, payment and trading systems.

If you are a OtherBank, you can sell your Freddie claims to others, and the business logic can change with the loan (this is the "smart contract" concept): Previously illiquid assets may be freely circulated in this model. . As I said, this space is not just a payment.

Obviously, I omitted a lot of details. The actual shared ledger is much more complicated .

But I hope this article can point out some directions. And, as I said before, this can't be achieved unless each of us has the right mindset for the bank's working model.

Addendum: In addition to regulation… What else can prevent us from lending as we please?

It is impossible to discuss risk without discussing the bank's balance sheet. There is such a reasonable question: If my analysis of how to issue loans and create deposits is correct, then why can't we lend and make a lot of deposits as we like? Is it because irresponsible, lending banks will kill themselves? Yes, that's the truth, and the risk will be expressed in two completely different things.

- Insufficient liquidity

The first problem facing banks is liquidity. Imagine if many customers want to take their deposits from the bank right away, but the bank doesn't actually have enough cash. What should the bank do?

As discussed above, banks can temporarily borrow some cash from others. But what if no one is willing to lend money to the bank? This is called insufficient liquidity : their assets are more than debt, so they are not going bankrupt…but they are unable to meet their repayment obligations. This is awkward!

In most countries, if this happens, the central bank will intervene and temporarily lend the funds to the bank. In fact, the ECB’s “emergency liquidity assistance” plan for Greek banks is a good example: hypothesis (or pretend to be pretending) that Greek banks are not bankrupt, and the ECB can lend more and more euros to Greek banks. To support Greek banks in dealing with deposit outflows.

From a regulatory perspective, the “liquidity coverage” clause, such as the Basel Accord, attempts to force banks to hold sufficient cash (or cash-like instruments) on their balance sheets to cope with foreseeable withdrawals.

- Insolvent

Another problem that banks may encounter is that they are insolvent – bankruptcy . It is also easy for you to understand what is going on here:

Imagine that some people looking for your loan are unemployed, or their company is bankrupt, and you immediately realize that they can't pay back your money.

For example, 2 million pounds in your previous loan cannot be recovered. So you “write down” in the loan book: the loan has changed from £10 million to £8 million… because now you know you can only recover £8 million.

Your assets are now worth 9.6 million pounds. But your debt has not changed. You still owe your customers and borrowed a bank of £10.6 million.

Your debt is greater than your assets. game over. Goodbye, you are bankrupt.

– Your loan loss means your assets are now less than debt. You are bankrupt. –

But, please note that if your loan only loses £500,000, then your bank will still function because your assets (11.1 million pounds) are still larger than the debt (10.6 million pounds).

-… If your loan has lost only £500,000, your bank will not go bankrupt. –

So you can lose money. But if you lose too much, you will be cold. So, what exactly determines how much loss you can afford? The answer is: capital-ownership .

Because of the bank's own capital, you can bear a loss of 500,000. Your shareholders have taken on these losses. Before the bad debts appeared, they had a residual claim for the company worth £1 million. A loss of £500,000 will reduce the value of their claim to £500,000. However, if you lose 2 million, which is greater than the £1 million “loss buffer” that capital can provide, you will go bankrupt.

Therefore, this is why regulators are so concerned about capital: the more capital a bank holds than the deposit or debt, the stronger the bank's ability to withstand losses in asset losses. Capital can absorb asset losses, but liabilities cannot. That's why we are always talking about “capital ratios”: “Capital ratios” refers to the proportion of capital in your assets.

But note: banks never “hold” capital. The assets and capital you hold are not assets… Instead, from a capital perspective, this is a bank fundraising mechanism.

And these phenomena can interact: If your bank is experiencing problems with insufficient liquidity, you may need to sell large amounts of assets at “jumping prices” and turn liquidity problems into solvency issues.

Original link:

Https://gendal.me/2015/07/05/a-simple-explanation-of-balance-sheets-dont-run-away-its-interesting-really/

Author: Richard Gendal Brown

Translation & proofreading: stormpang & Ajian

(This article is from the EthFans of Ethereum fans, and it is strictly forbidden to reprint without the permission of the author.

We will continue to update Blocking; if you have any questions or suggestions, please contact us!

Was this article helpful?

93 out of 132 found this helpful

Related articles

- Why did the USDT at the time of the big rise suddenly increase by 300 million?

- Who is Hodlonaut? CSW is looking for him, the Bitcoin community is protecting him.

- How does the virtual currency mine circle respond to the “elimination” crisis?

- The Brexit delay in the United Kingdom is a big blow to the BTC "back pot"? Things have to start from the previous big rise

- After many times of theft, the Korean exchange Bithumb lost $180 million last year.

- Well-known investment institution Polychain: Manage assets from $1 billion to near waist

- Hardcore bitcoiner development guide