Extensive Article The Iron Curtain of Regulatory Control in the United States Has Fallen, What Tomorrow Will Crypto Face?

Fall of US Regulatory Control What's Next for Crypto?Author: Phoenix Capital

Summary

- The Ripple case has achieved a partial victory in the programmatic sales, avoiding being classified as securities sales; we carefully analyze the logic of the court’s judgment and believe that there may be obvious errors in the factual determination, which may be overturned later.

- We analyze the historical origins and basic connotations of securities laws and believe that tokens with the narrative of “project parties doing things” are close to the definition of securities laws, so a relatively high proportion of tokens in the future may be classified as securities; but the regulatory demands of the SEC currently go beyond the reasonable scope of securities laws.

- The probability of Staking/yield farming being classified as securities is significantly higher than that of general token sales.

- Compared to the regulation of CeFi, the regulation of DeFi is earlier; in addition to securities laws, there are also uncontroversial regulatory issues such as KYC/AML that have not yet been resolved.

- Even if a large number of altcoins are classified as securities, it will not be the end of the industry. Large-cap tokens have the conditions to seek compliance in the form of securities; small-cap tokens may continue to exist in non-compliant markets for a long time, but they can still indirectly obtain liquidity from compliant markets. As long as there is a clear regulatory framework, no matter what kind it is, the industry can find new paths and models for long-term development.

Long-awaited (temporary) victory – Interpretation of the Ripple case

Ripple Labs obtained a partial favorable judgment from the New York District Court on July 13, 2023, and the crypto market responded with a sharp rise. In addition to XRP itself, a series of tokens previously classified as securities by the SEC also saw significant increases.

As we will discuss later, we still have a long way to go before the crypto industry truly enters an era of clear regulation. But there is no doubt that Ripple Labs’ partial victory is still one of the most important things in the crypto industry in 2023.

Below are some important disputes between US regulators and the crypto industry before SEC vs Ripple Labs.

- Here is a list of cryptocurrency observations for the next week $LTC halving event, Evmos 2.0 launch…

- Outlier Ventures Data-Driven Token Design and Optimization

- EIP-7377 An excellent solution for migrating from EOA to smart contract wallets before the popularization of account abstraction.

It is not difficult to see that almost all major disputes before were concluded with the failure or compromise of crypto companies.

In a sense, this is the first meaningful victory for the crypto industry in the war with US regulators, even if it is only a partial victory.

There have been many detailed interpretations of the specific content of this court judgment, and we will not go into it here; interested friends can read the long tweet by LianGuairadigm Policy Director Justin

You can also read the original text of the court judgment yourself

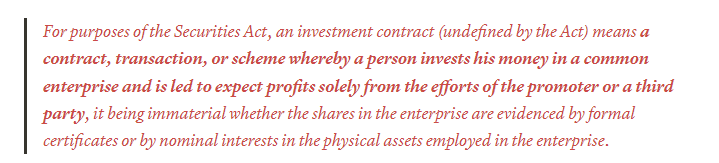

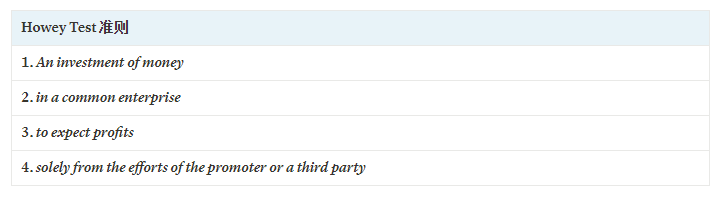

Before we delve into the detailed interpretation of this judgment, let’s briefly introduce the core criteria for defining securities in the US legal system that we often hear – the Howey Test.

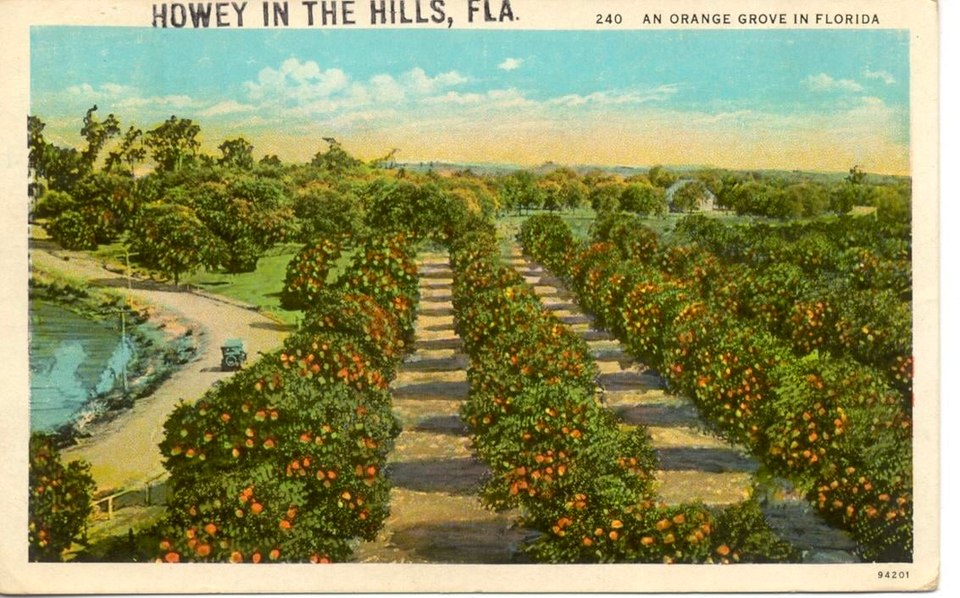

Howey Test, Orange Groves, and Cryptocurrencies

To understand all the disputes surrounding cryptocurrency regulations today, we must go back to the sunny Florida of 1946, to the cornerstone case of securities law determination, SEC vs Howey.

(The following story synopsis was mainly written by GPT-4)

In the post-World War II era, specifically in 1946, the W.J. Howey company owned a bountiful citrus grove in the picturesque state of Florida.

In order to raise more investment, Howey company introduced an innovative plan that allowed investors to purchase parcels of land in the citrus grove and lease the land to Howey for operation. Investors would then receive a portion of the profits. In that era, this proposal was undoubtedly attractive to investors, as owning one’s own land was a captivating prospect.

However, the SEC did not buy into this. The SEC believed that the plan offered by Howey company essentially constituted a security, but Howey company did not register it with the SEC, which clearly violated the Securities Act of 1933. As a result, the SEC decided to file a lawsuit against Howey company.

This lawsuit eventually reached the Supreme Court. In 1946, the Supreme Court made a historic ruling on SEC vs Howey. The court sided with the SEC, ruling that Howey company’s investment plan met the definition of a security and therefore required registration with the SEC.

The Supreme Court’s judgment on Howey company’s investment plan was based on the four basic elements of the so-called “Howey Test”. These four elements are: investment of money, expectation of profits, common enterprise, and profits derived solely from the efforts of others. Howey company’s investment plan met these four elements, and thus the Supreme Court determined it to be a security.

Firstly, investors invested money to purchase parcels of land in the citrus grove, which fulfilled the first element of the “Howey Test” – investment of money.

Secondly, it was evident that investors purchased the land and leased it to Howey company with the expectation of earning profits, which satisfied the second element of the “Howey Test” – expectation of profits.

Thirdly, the relationship between investors and Howey company constituted a common enterprise. Investors contributed their investments, while Howey company operated the citrus grove, with both parties working together to obtain profits. This fulfilled the third element of the “Howey Test” – common enterprise.

Lastly, the profits from this investment plan primarily came from the efforts of Howey company. Investors only needed to invest their money and could enjoy the fruits of the labor, which satisfied the fourth element of the “Howey Test” – profits derived solely from the efforts of others.

Therefore, based on these four elements, the Supreme Court concluded that Howey company’s investment plan constituted a security and required registration with the SEC.

This ruling had far-reaching implications and formed the widely referenced “Howey Test”, which defines the four basic elements of an “investment contract”: investment of money, expectation of profits, common enterprise, and profits derived solely from the efforts of others. These four elements are still used by the SEC today to determine whether a financial product constitutes a security.

Above is the accurate explanation of securities in the highest court opinion in 1946, which can be broken down into the following four commonly used criteria:

The law is truly fascinating. It often uses abstract and simple principles to guide the ever-changing specific situations in the real society, whether it is an orange grove or a cryptocurrency.

Why do we need securities law

In fact, it doesn’t matter how the definition of securities is determined. There is no substantial difference in calling something a security or not; the key is what legal responsibilities are derived from the economic nature of securities, that is, why something with these four attributes of the Howey Test needs an independent legal framework to supervise it.

The Securities Act of 1933, which was produced more than a decade before the Howey Test, explicitly explains why we need securities law.

Often referred to as the “truth in securities” law, the Securities Act of 1933 has two basic objectives:

1) require that investors receive financial and other significant information concerning securities being offered for public sale; and

2) prohibit deceit, misrepresentations, and other fraud in the sale of securities.

The starting point of securities law is very simple – it is to ensure that investors can obtain sufficient information about securities and be free from deception. Conversely, the responsibilities imposed on securities issuers are also very simple, the core is disclosure, which must be complete, timely, and accurate disclosure of important information related to securities.

The reason why securities law has such a goal is because securities, due to the fact that the source of investors’ returns on securities is the efforts of third parties (active LianGuairticiLianGuaint), so third parties have unequal information and influence on securities prices compared to investors. Therefore, they need to fulfill their disclosure obligations to ensure that this inequality does not harm investors.

Commodity markets do not have similar regulatory requirements because there is no such third party, or in the context of crypto, it is easier to understand using the term “project party.” Gold, oil, and sugar do not have project parties. The crypto market generally favors the CFTC and dislikes the SEC, but this is not because regulators have personal preferences and therefore have different attitudes towards crypto; the difference in regulating commodities and securities is based on the inherent differences in the nature of the two financial products. Because there is no project party with unequal advantages, the regulatory framework for commodities law naturally becomes much easier.

The fundamental reason for the existence of securities law is the existence of third parties or project parties with information and influence advantages; restraining the infringement of investor interests by third parties/project parties is the fundamental purpose of securities law; requiring project parties to make complete, timely, and accurate information disclosure is the main means of implementing securities law.

Are Project Actions Equivalent to Securities?

While studying the history of U.S. securities law, I came across a phrase commonly heard in the crypto industry, which led me to a simple and effective criterion for determining whether a token is a security – whether investors care about the actions of the project team.

If “project actions” are meaningful to investors, it means that the returns on their investment are influenced by the project team’s actions, which obviously satisfies the four criteria of the Howey Test. Based on this, we can easily understand why BTC is not a security, because BTC does not have a project team. Meme coins are similar in this regard – they are just numbers on the ledger of the ERC-20 protocol, without a project team behind them, and therefore not considered securities.

If there is a project team that is actively engaged in actions, and if the actions of the project team, whether good or bad, affect the token price, then the definition of a security is met. Because there is a project team, they have information unknown to other investors and have a greater impact on the token price, so they need to be regulated to ensure that they do not do anything harmful to investor interests. The logic is simple: “What the project team does is important” → “The project team can manipulate the market” → “The project team needs to be regulated by securities law.”

If you agree with this logic, you can judge for yourself which tokens in the crypto industry are reasonably classified as securities.

We believe that if investors have expectations or concerns about the “project actions,” then the token is highly likely to meet the definition of a security. From this perspective, it seems logical that a significant proportion of tokens are classified as securities.

However, the current SEC wants even more. Based on Gary’s public statements, he only recognizes that BTC is not a security. For most other tokens, he firmly believes they should be classified as securities, while a few tokens, such as ETH, currently have a relatively ambiguous status. Recently, the Coinbase CEO mentioned in an interview that before the SEC filed a lawsuit against Coinbase, they requested Coinbase to delist all tokens except BTC, but Coinbase refused.

We believe it is unreasonable to classify pure meme coins that have no project team operations or highly decentralized pure payment tokens as securities. The SEC’s demands go beyond the reasonable scope of securities law, making it more difficult for the industry and the SEC to resolve their conflicts in a simple manner.

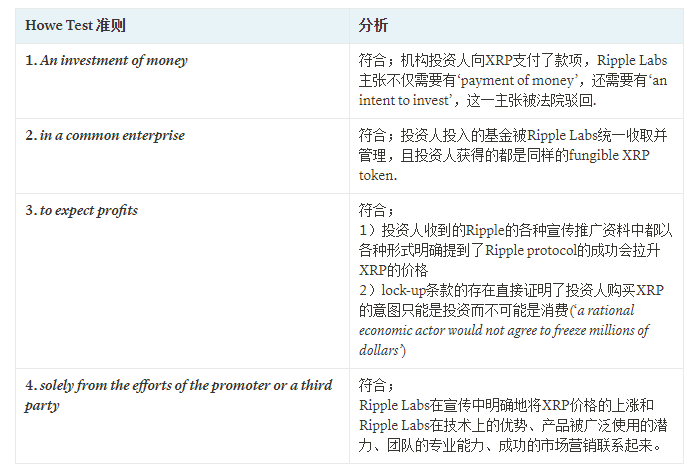

Returning to the SEC vs Ripple Labs judgment, let’s highlight a few key points:

-

XRP itself is not a security, and the specific circumstances of XRP sales need to be analyzed (i.e. the sales process, methods, and channels) to determine whether they constitute securities sales. We will elaborate on this point later on. A token is just a token. A token is NEVER a security.

-

The court analyzed three forms of XRP sales: institutional sales, programmatic sales, and others. In the end, it determined that institutional sales constitute securities, while the other two do not.

-

Reasons for determining that institutional sales constitute securities sales:

-

Reasons why programmatic sales do not constitute securities sales:

-

Ripple Labs did not make any direct commitments to these investors, and there is no evidence in Ripple Labs’ promotional materials to suggest widespread dissemination among these investors.

-

These investors have a low level of complexity and cannot demonstrate a sufficient understanding of how their actions can affect the price of XRP tokens.

-

It is not difficult to see that the court’s determination of the core argument of programmatic sales is based on the fourth factor of the Howey Test, which is that these investors did not expect to profit from Ripple Labs’ efforts.

-

XRP buyers did not expect to profit from Ripple Labs’ efforts because:

-

In this case, investors are unsure whether they are buying from Ripple Labs or from other XRP sellers. Most of the XRP trading volume does not come from Ripple Labs’ sales, so most XRP buyers do not directly invest funds into Ripple Labs.

-

This ruling by the district court is not final and binding; it is almost certain that the SEC will appeal. However, the appeal process is likely to be lengthy, and we may have to wait for months or even years to see the outcome of the new appeal ruling. During this time, the court’s ruling will substantially guide the development of the industry.

Setting aside our position as cryptocurrency investors; purely from a legal standpoint, we believe that the court’s logic in not considering programmatic sales as securities is not very persuasive.

Here are two articles by senior legal professionals who hold similar opposing views. It is recommended that you take the time to read them, as our analysis also draws on some of their perspectives.

https://www.linkedin.com/pulse/ripple-decision-cause-crypto-celebration-momentarily-best-stark/

Ripple Labs Ruling Throws U.S. Crypto-Token Regulation into Disarray

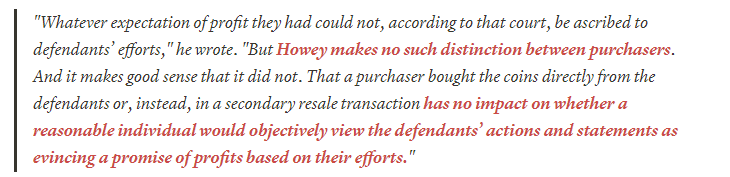

First of all, we need to note the original text of the Howey Test, which states ‘…expect profits solely from the efforts of the promoter or a third party…’ This clearly indicates that profits can come from the promoter or a third party, meaning that the identity of the seller is not important, or in other words, the source of effort does not need to be the seller or promoter. As long as there is such a third party, it is sufficient. Therefore, it is not important for investors to know who they are buying from or whether the seller is the third party responsible for the profits. As long as investors recognize that the appreciation of this asset comes from the efforts of a third party, it is sufficient. Therefore, the court’s mention of blind buy/sell and the fact that buyers do not know whether they are buying XRP from Ripple Labs or others is irrelevant to the Howey Test.

The essence of the problem still lies in whether the investors in programmatic sales are aware of the correlation between the rising price of the XRP tokens they purchased and the efforts of Ripple Labs.

The main argument of the court is that 1) Ripple Labs did not directly promote to retail and there is no evidence to prove that their materials (such as white papers) were widely spread among retail, and 2) Retail investors do not have the cognitive ability to recognize the connection between XRP tokens and the work Ripple Labs has done in technology, products, and marketing.

First of all, this is a matter of fact, not a logical issue, and we cannot complete the argument here. XRP is an old project, and we do not have a clear perception to judge the cognition of retail investors at that time.

However, based on our limited experience, for most project tokens held by retail investors, they are aware that the project team’s efforts in upgrading technology, launching the mainnet earlier, improving the usability of the product, increasing TVL, engaging in more ecological cooperation, and leveraging KOLs have an impact on the price of their tokens.

In the world of crypto, KOLs, Twitter, and small or large Telegram groups have become the bridge between most project teams and users, the territory for promoting to retail investors. In small or large projects, we often hear people discussing how the “community” is doing. Most project teams have a token marketing/community team responsible for contacting exchanges around the world, hiring KOLs, and helping promote project progress and major developments.

We believe that the factual determination of programmatic sales in this court ruling is biased, and we also agree with the views of many legal professionals that there is a high possibility of overturning this part of the ruling in the future.

(Just one week after the completion of this article, on the day it was about to be published, we happened to see in the SEC vs Terraform Labs case that the new judge rejected the logic of the ruling in SEC vs Ripple Labs – the logic that no matter where investors buy tokens from, it does not affect the expectations formed by investors regarding the efforts of the project team on the token price.)

Off-topic: Airdrops that do not involve money can also be considered securities sales. This is from an article by John Reed Stark. In the late 1990s Internet bubble, many companies distributed free stocks to users via the Internet. In subsequent legislation and trials, these actions were considered securities sales. The reason is that although users did not pay money to exchange for these stocks, they provided other values, including their personal information (which had to be filled out when registering to receive stocks), and helped the company distributing stocks gain attention, forming a substantial value exchange.

SEC Enforcement Director Richard H. Walker said at the time, “Free stock is really a misnomer in these cases. While cash did not change hands, the companies that issued the stock received valuable benefits. Under these circumstances, the securities laws entitle investors to full and fair disclosure, which they did not receive in these cases.”

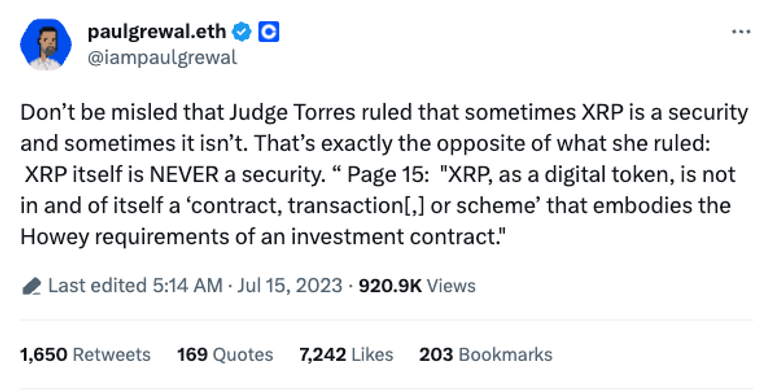

A token is just a token. A token is NEVER a security.

As pointed out by Coinbase CLO Lian Guaiul, this is actually the most important but not fully understood sentence in the entire judgment.

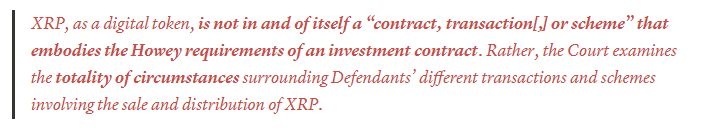

Even the Telegram case, which has a very different interpretation from the Ripple case, the judge also made a similar statement. This is the highly consistent view of the two judges in the two cases:

These two judgments consistently indicate an important point:

A token is just a token —— contrary to what many people mistakenly believe, the court does not consider XRP to be a security sometimes and not other times —— a token itself can never be a security.

What can potentially be considered a security is the entire set of actions (‘scheme’) of selling and distributing tokens, and it is not a question of whether a particular token is a security, but rather whether a specific token sales activity is a security. We can never reach a conclusion on whether a token is a security based solely on the analysis of that token, but must analyze the overall situation of this sales activity (‘entirety of …’, ‘totality of circumstances’).

The two judges with significant conflicts of opinion both insisted that whether it is a security should be judged based on the sales situation rather than the inherent attributes of the token —— this consistency also represents a higher possibility of future adoption of this legal logic compared to the judgment against programmatic sales, and we also believe that this judgment indeed has stronger logical rationality.

A token is just a token. A token is NEVER a security.

Digital tokens and stocks are fundamentally different. A stock itself is a contract signed between an investor and a company, and the trading in the secondary market itself represents the trading and transfer of this contractual relationship. On the other hand, as the judge said in the Telegram case, a digital token is nothing more than an alphanumeric cryptographic sequence, and it cannot itself constitute a contract. It can only have the economic substance of a contract in specific sales contexts.

If this legal viewpoint is adopted by all subsequent courts, then in the future, the SEC’s burden of proof in the prosecution process will be significantly increased. The SEC cannot obtain regulatory authority over all activities such as issuance and trading of a token by proving that a particular token is a security. It needs to prove the overall situation of each token transaction one by one to constitute a securities transaction.

In the Ripple case, it is also explicitly stated that the court cannot judge whether the secondary sales of XRP constitute securities transactions, and they need to evaluate the specific circumstances of each transaction to make a judgment. This poses great difficulties for the SEC to regulate secondary trading, and in a sense, it may be impossible to accomplish; this essentially gives the green light to secondary transactions of tokens. Coinbase and Binance.US also relisted XRP quickly after the penalty was announced.

Again, it is too early to consider this as a legal rule just based on the opinion of this precedent; however, the legal logic of “A token is just a token” will indeed increase the legal obstacles that future SEC-regulated secondary exchanges will face.

Looking to the Future – Where are the Risks and Opportunities?

The Sword of Damocles Hanging over Staking

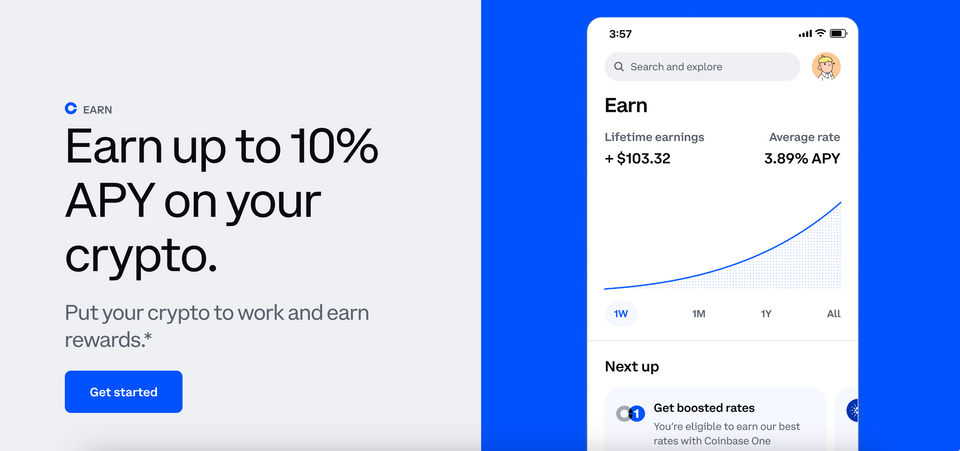

ETH staking has been one of the strongest tracks in the industry since 2023; however, the regulatory risk of staking services is still the Sword of Damocles hanging over this super track.

In February 2023, Kraken agreed to settle with the SEC and closed its staking services in the United States. Coinbase, which was also sued for its staking services, chose to continue the fight.

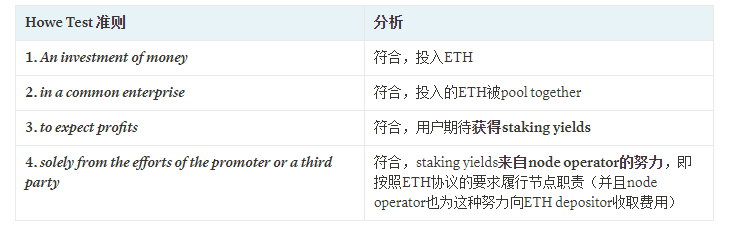

If we return to the framework of the Howey Test and analyze objectively, staking services can indeed be considered securities for valid reasons.

Kraken chose to settle. So what are Coinbase’s reasons for insisting that staking services are not securities?

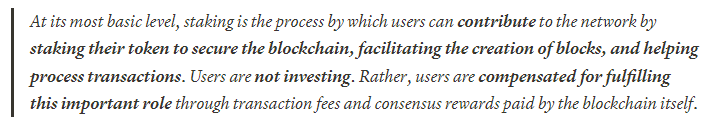

Coinbase put forward an interesting argument, stating that “staking users are not investing but rather being compensated for their contributions to the blockchain network.”

This argument is appropriate for independent stakers. However, as delegate stakers, they do not directly carry out tasks such as verifying transactions and ensuring network security. Instead, they delegate their tokens to other node operators who use their tokens to perform these tasks. Stakers are not direct laborers; in fact, they are more like buyers of orange grove land in the Howey case, owning land/capital (ETH) and entrusting others to cultivate it (node operation) to earn profits.

Providing capital itself is not labor, as the returns obtained from providing capital are capital gains, not compensation.

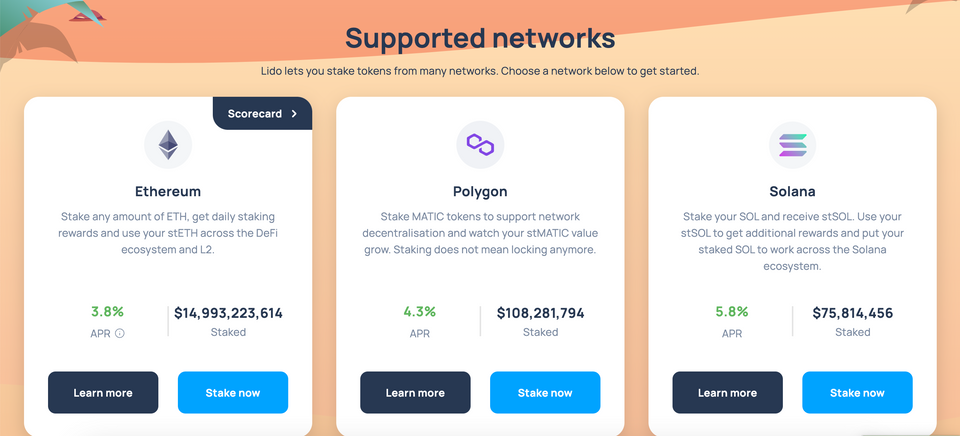

The situation of decentralized staking services may be more complex, and different types of decentralized staking may ultimately receive different legal judgments.

Most of the four criteria of the Howey Test are similar in centralized and decentralized staking, with the difference possibly lying in whether a common enterprise can exist. Therefore, the staking model that pools all users’ ETH into the same pool, even if it is decentralized, clearly aligns well with the four criteria of the Howey Test.

In SEC vs Ripple Labs, the argument that Ripple won in favor of Programmatic Sales (where both the buyer and seller do not know each other and there is no direct solicitation) seems to be difficult to protect staking services here.

Because apart from directly buying cbETH/stETH in the secondary market, in the case where the pledger pledges ETH to Coinbase/Lido and at the same time obtains cbETH/stETH, obviously 1) the buyer knows who the issuer is, and the issuer knows who the buyer is, 2) the issuer clearly promotes the source of the income.

Similarly, besides staking in PoS chains, **various stake/lock token yield products in DeFi are also highly likely to meet the definition of securities**—if establishing the relationship between token price and project effort is difficult for pure governance tokens, in the context of staking to earn yield, the logic is clear and simple; at the same time, even though the reason why programmatic sales are not considered securities in the Ripple case is difficult to apply here—

1) Users hand over tokens to the pledging contract developed by the project team, and the pledging contract returns income to the users, the income comes from the income generated by the project contract opened by the project team;

2) Moreover, in the process of interaction between users and the pledging contract, the contract also involves directly promoting income to users and explaining the income (promotion), which is difficult to justify using the reasons in XRP programmatic sales.

In summary, for projects that provide staking services (in PoS chains, in DeFi projects), due to 1) clear income distribution, 2) direct promotion and interaction with users, the possibility of being recognized as securities is further increased compared to projects in the general sense of “the project team doing things”.

Securities law is not the only regulatory risk

Securities law is the focus of this article, but it is necessary to remind everyone that securities law is only a small part of the entire regulatory framework for crypto—of course, because it is the more stringent part, it deserves special attention. Whether a token is ultimately considered a security or a commodity or something else, there are some more fundamental legal responsibilities that are common, and there are also many regulatory agencies other than the SEC and CFTC that will be involved. The content involved here is worth another lengthy article, and we will only briefly provide an example for reference here.

This is the KYC-related responsibility centered on anti-money laundering (AML) and counter-terrorist financing (CTF). No financial transaction can be used for money laundering, terrorist financing, and other financial crimes, and any financial institution is responsible for ensuring that the financial services provided are not used for these financial crimes. In order to achieve this goal, all financial institutions must take a series of measures, including but not limited to KYC, transaction monitoring, reporting suspicious activities to regulators, and maintaining accurate records of historical transactions, etc.

This is a fundamental and undisputed basic law in financial regulation, and it is also a field regulated by multiple law enforcement agencies, including the Department of Justice, the Department of the Treasury/OFAC, the FBI, the SEC, and so on. Currently, all centralized crypto institutions are also complying with this law and conducting necessary KYC for all customers.

The main potential risk in the future lies in DeFi, whether DeFi needs and is possible to comply with similar regulations as CeFi, requiring KYC/AML/CTF; and whether this regulatory model may harm the foundation of permissionless, which is the value of blockchain.

In principle, since financial transactions are generated in DeFi, it is necessary to ensure that these financial transactions are not used for money laundering and other financial crimes, so the inevitability of regulatory laws is unquestionable.

The challenge lies mainly in defining the regulatory objects. Essentially, the occurrence of these financial transactions is based on the services provided by a piece of code on Ethereum. So, should it be the Ethereum nodes running this code or the project developers who wrote this piece of code that should be regulated? (This is why there is controversy over the arrest of Tornado Cash developers) Additionally, the decentralization of nodes and the anonymity of developers make it even more difficult to implement this supervision—this is a problem that legislators and law enforcement agencies must solve, and it is questionable how they will solve these problems; but it is unquestionable that no regulator will allow activities such as money laundering and arms trading on an anonymous blockchain, even if such transactions account for less than one-thousandth of blockchain transactions.

In fact, on the 19th of this month, four senators from the U.S. Senate (two Republicans and two Democrats, so it’s a bipartisan bill) have proposed legislation called the Crypto-Asset National Security Enhancement and Enforcement (CANSEE) Act targeting DeFi, with the core requirement being that DeFi must comply with the same legal responsibilities as CeFi:

How to ensure the implementation of AML/CTF in DeFi transactions is a regulatory challenge that the industry must face, in addition to that, for example, whether the tokens are classified as securities or commodities, there are also strict requirements for prohibiting market manipulation, and how these issues will be addressed in the crypto industry is a challenge that the industry must face in the future.

Below are some typical forms of market manipulation, and I believe that anyone who has speculated in coins has experienced more than one textbook-like case of these behaviors.

What if Crypto Loses – Securities Law Will Not Kill Altcoins

We do not have enough legal and political knowledge to predict the ultimate outcome of these legal disputes, but objective analysis makes us realize that it is logical for most tokens to be recognized as securities in accordance with US securities laws. So we must reason or imagine what the future of the crypto industry will look like if most tokens are recognized as securities.

Some tokens will choose to become compliant securities

First of all, from an economic cost perspective, the economic cost of listing compliance is not so terrible. For large-cap tokens with a market value of over 1 billion FDV, they are likely to be economically supportable.

A simple comparison of market capitalization reveals that there are a large number of tokens that can be compared to listed companies, especially tokens with a market value of 1 billion FDV or more. There is every reason to believe that they are capable of supporting the compliance costs of a listed company.

-

There are approximately 2,000 companies in the US with a market value of 100 million to 1 billion, and approximately 1,000 companies with a market value of 1 billion to 5 billion.

-

In the current bear market environment for altcoins, there are also about 40-50 tokens with FDV>1 billion and about 200 tokens with FDV 100 million to 1 billion in the crypto market. It can be anticipated that in a bull market, more tokens will enter the market value of 100 million+ / 1 billion+.

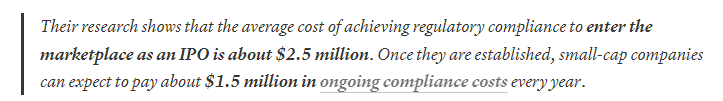

We can also refer to some research on the compliance costs of listed companies. One relatively reliable estimate is the SEC’s calculation of the listing compliance costs for small and medium-sized companies:

The conclusion is that the IPO costs are around 2.5 million, with annual recurring costs of around 1.5 million. Taking into account inflation in recent years, 3-4 million for IPO and 2-3 million for annual recurring costs sound like reasonable estimates. Additionally, this number is certainly positively correlated with the size of the company itself. Microcap companies with several hundred million dollars should have lower costs than this average. This is certainly not a small amount of money, but for large projects with a team of hundreds of people, it is not an unacceptable cost either.

What is relatively more uncertain is how to resolve the compliance issues in the history of these projects.

Listing a stock will require an audit of the company’s historical financial situation. Tokens are not equity, so the required disclosures and the listing of stocks should be different, and a new regulatory framework is needed to make clear definitions. But as long as there are clear rules, there are ways to adjust and handle. Companies with historical financial issues can also obtain listing opportunities through methods such as restating historical financial statements.

While the cost of compliance is acceptable, it is also quite high. So do project parties have the incentive to do so? There is obviously no simple answer to this question.

First of all, compliance will indeed add a lot of burden to many project parties and reduce a lot of room for action—cannot do “market value management,” cannot engage in insider trading, cannot make false advertising, selling tokens requires announcements, etc., which does touch upon the fundamentals of many business models.

However, for projects with particularly large market capitalization, obtaining broader market liquidity, exposure to more and deeper-pocketed investors, and comprehensive regulatory approval are important conditions for them to take the next step in both market value growth and project development.

“Illegal harvesting may be fierce, but the leek pond is small; legal harvesting requires restraint, but the leek pond is large.”

As the project grows in scale, the potential benefits of non-compliant operations versus the opportunities brought by the vast market and capital accessible through compliance, the balance is increasingly tilting towards the latter. We believe that leading public chains/layer2 and blue-chip DeFi projects will take this step and move towards a completely compliant operating model.

The long-term coexistence and mutual dependence of compliant and non-compliant ecosystems

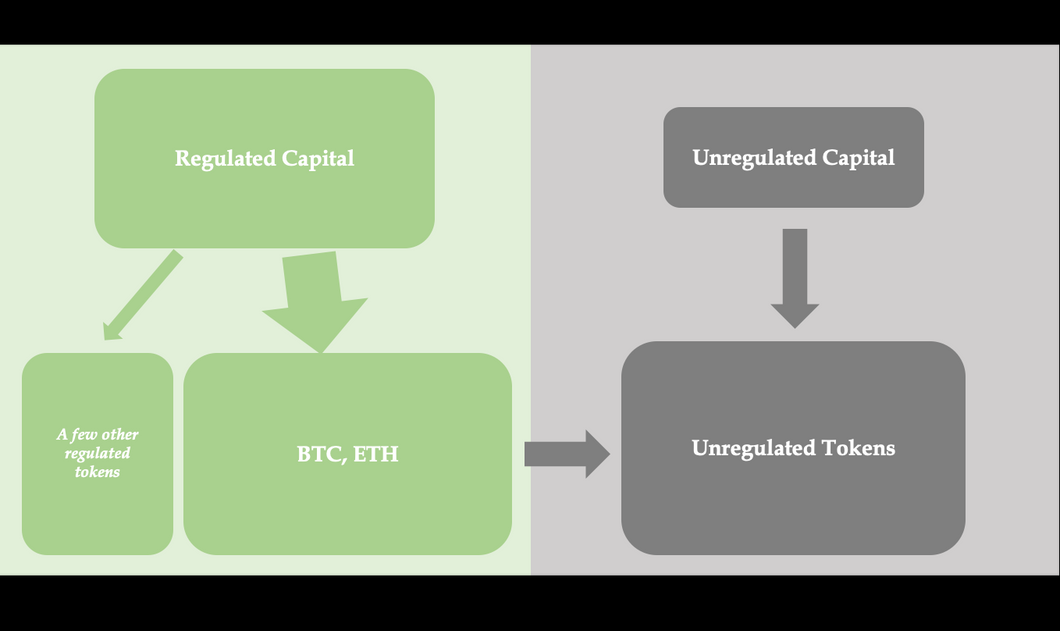

Of course, most projects cannot and will not embark on the path of securities compliance; the future crypto world will be composed of two clearly defined but closely connected parts: compliance and non-compliance.

This coexistence pattern already exists today, but the influence of the compliant ecosystem in the crypto world is still relatively small. With the clarity of regulatory frameworks, the influence and importance of the compliant ecosystem will continue to grow. The development of the compliant ecosystem will not only significantly increase the overall scale of the crypto industry but also provide liquidity overflow to the non-compliant ecosystem through the form of rising prices of mainstream assets.

Large projects become compliant, while small projects remain in the non-compliant market and can still benefit from the liquidity overflow of the compliant market. The two markets complement each other, and securities laws will not be the end of crypto.

Peace is more important than victory

On the judicial side, SEC vs Ripple is still undecided, and SEC vs Coinbase/Binance has just begun – it may take several years for these lawsuits to reach a conclusion.

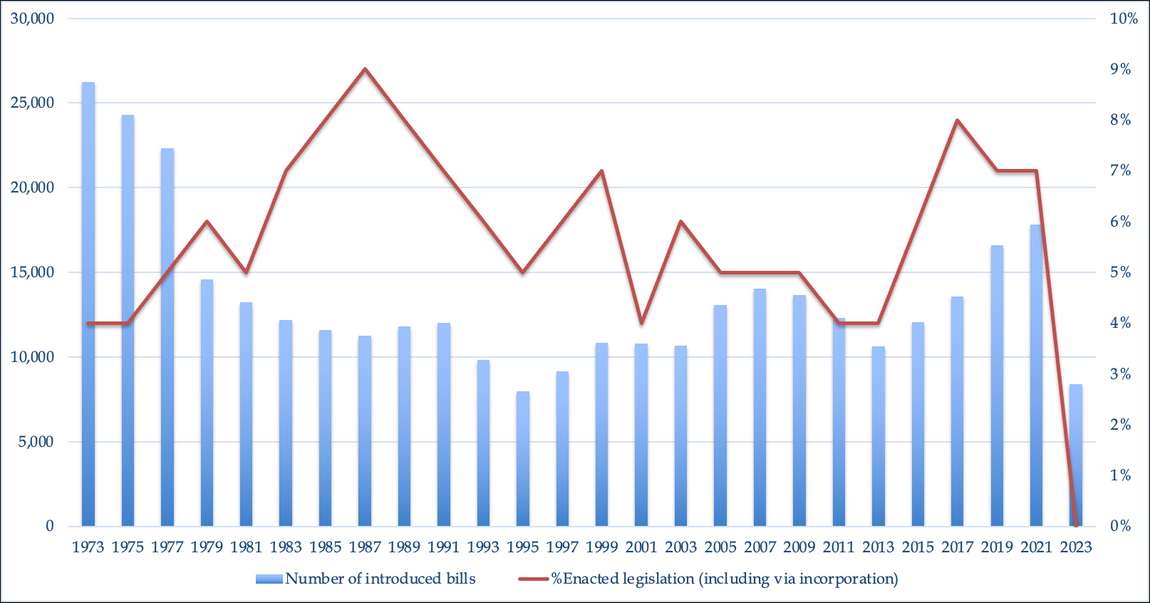

On the legislative side, multiple crypto regulatory bills have been submitted to both houses since July, including the Financial Innovation and Technology for the 21st Century Act, the Responsible Financial Innovation Act, and the Crypto-Asset National Security Enhancement and Enforcement – there have been more than 50 crypto regulatory bills submitted to both houses in history, but we are still far from a clear legal framework.

The worst outcome for the crypto industry is not most tokens being classified as securities, but the time and space wasted and the resources and opportunities lost in the long-term absence of a clear regulatory framework.

The escalation and intensification of conflicts between regulators and the crypto industry is good news because it means that the time for convergence and resolution of these conflicts is getting closer.

The judgment day for Ripple Labs is July 13th, and the next day, July 14th, is the anniversary of the French Revolution. This reminds me of the turmoil and unrest in France after the revolution ended. However, it was during that chaotic period that the foundation of modern law, the French Civil Code, was eventually established. We hope that even though the crypto industry is currently experiencing confusion and turbulence, it will eventually find its direction and establish a set of norms and codes that can coexist harmoniously with the outside world.

We will continue to update Blocking; if you have any questions or suggestions, please contact us!

Was this article helpful?

93 out of 132 found this helpful

Related articles

- LianGuai Daily | Sequoia Capital reduces the size of its cryptocurrency fund to $200 million; French privacy regulatory agency launches investigation into Worldcoin.

- African Gold Rush I Help Chinese Citizens with Worldcoin KYC, Earning up to 20,000 RMB per day

- Interview with EthStorage Founder How to Scale Ethereum’s Storage Performance through Layer 2 Expansion?

- The Fit21 encryption bill of the American Republican Party has been approved and will enter the full deliberation of the House of Representatives.

- LianGuai Paradigm Stablecoins have their unique characteristics and should not be included in the regulatory frameworks of banks and securities.

- Raft’s ten thousand character research report Decentralized lending protocol, the second largest LSD stablecoin $R issuer.

- Be vigilant of hidden Rug Pulls, as well as exit scams caused by contract storage.