Is something with no elasticity in supply not suitable to serve as currency?

Is a currency without supply elasticity unsuitable?Author: Anony, BTCStudy

Among the arguments that have been made to criticize Bitcoin, there is one that goes like this: “After reaching its maximum supply, the supply of Bitcoin will no longer increase. Something with such inelastic supply is not suitable to be used as money.” This viewpoint is special because it targets the value proposition of Bitcoin – that it is a currency with a limited supply, which is why many people love it and think it has value.

Furthermore, this viewpoint presents two arguments:

(1) In certain situations, especially when the economy enters a downturn, increasing the money supply can stimulate economic activity and revive the economy; similarly, in certain situations, reducing the money supply can have benefits;

- Web3 Social Resurgence Who will be the next phenomenon-level application among friend.tech, Telegram, and others?

- Tether CTO reveals the truth about stablecoin reserves

- Vitalik’s New Article Explained in Detail Why ‘Adding Off-Protocol Functionality’ Is an Extremely Important Consideration Factor

(2) It is almost inevitable that people will forget or lose money in their daily lives. This effect accumulates over time and leads to a continuous decrease in the amount of currency in circulation, resulting in a shortage of money, which is detrimental to market trade [1].

I believe that these arguments are unfounded. However, in order to analyze these viewpoints, we must first understand the nature of money itself – essentially, money is also a commodity with its own market and price.

The Market and Price of Money

In summary, money has two prices: purchasing power and interest rates.

Purchasing power refers to the proportion of money exchanged for other goods and is sometimes referred to as “price level”. How much can a certain amount of money (e.g. 100 dollars/yen/grams of gold) buy? That is the purchasing power of money.

Interest rates, on the other hand, refer to the exchange ratio of the same currency in different time periods. How much is 100 yuan today equivalent to on the same day next year? When you lend 100 yuan to someone, how much interest do you demand? In such lending scenarios, the exchange involves cash (or cash-like equivalents) in different time periods (current, one year later), and this exchange will inevitably involve interest. The reason for this is simple: cash itself is useful, “a bird in the hand is worth two in the bush.” In order to exchange the money people have in their hands, a certain cost must be paid.

Some argue that there are four prices for money, with the other two being “parity” and “exchange rate” [2]. The former refers to the exchange ratio between the same but different types of currency, such as the exchange ratio between cash and bank deposits, which generally needs to be 1:1. The latter refers to the exchange ratio between different currencies. These concepts are useful in certain scenarios, but we don’t need to delve into them here.

Purchasing power and interest rates, like the prices of other commodities: (1) arise in market transactions; (2) are regional; (3) constantly change.

The purchasing power of money arises in the comparison, negotiation, and transaction of prices by consumers; similarly, interest rates on money are constantly matched between the supply and demand sides of money savings. The purchasing power of money also has regional variations, where the same amount of money may buy different quantities and qualities of goods in different places. In real life, the continuous real-time changes of these two prices are not observed because price adjustments also require resources and time, and their absence does not mean that they will never change.

Just like the prices of other goods, the price of currency is also aimed at coordinating the distribution of currency among different populations and different time periods in order to meet people’s various needs: purchasing goods and services with cash, obtaining necessities of life, saving currency to support long-term plans, saving currency to hedge against risks, and meeting turnover needs. In the past, in the era of metallic currency, the price of currency could also guide the production of new currency.

So, what impact does changes in the quantity of currency have on the price of currency? Let’s start with purchasing power.

Fisher’s equation

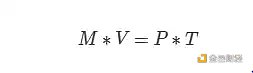

We take a mathematical formula that is often quoted in monetary theory as our starting point:

Here, M represents the quantity of currency; V represents the velocity of currency circulation; P represents the price level (or purchasing power level); T represents the quantity of goods being traded. This equation must hold true because it expresses a kind of “tautology” (also known as “tautological repetition”) – it describes two aspects of the same process (market transactions).

The right side of the equation represents the transaction volume in the market. “Price level” is not something that actually exists; it is an abstract concept derived by people, and the process of abstracting it is to divide the market transaction volume by the quantity of goods. So, multiplying it by the quantity of goods is exactly equal to the market transaction volume. The left side of the equation represents the other aspect of the transaction process – regardless of the size of the transaction volume, it means that people have exchanged the same quantity of currency units. However, currency does not disappear after the transaction; people will continue to let it participate in circulation, so we need to multiply it by a velocity.

Economists often use this equation to illustrate the consequences of an increase in the “quantity of currency” – let’s not worry about the strict definition of this concept, what counts as currency and what does not – assuming that V and T remain unchanged, the result is an increase in P, or a decrease in the purchasing power of currency.

This kind of reasoning is useful – it shows us that if the factors that cause changes in the quantity of currency do not cause the velocity of currency circulation and the quantity of goods being exchanged to change in the opposite direction, then an increase in the quantity of currency will lead to a decrease in the purchasing power of currency. However, it is not perfect – we cannot guarantee that these two factors will not change in the opposite direction.

Next, we will learn about another theory that is older but actually more profound.

Cantillon effect

Cantillon [3] was a merchant who lived in the early 18th century. He keenly observed a phenomenon: when the quantity of currency increases, not everyone receives the newly issued currency at the same time, which also means that not everyone is aware that the value of the currency is decreasing at the same time; the newly created currency, like ripples caused by throwing a stone into water, gradually spreads outward with the economic activities of the first people who receive this currency, until it reaches everyone; in this process, the earlier a person receives the currency, the greater benefits they can obtain from the new currency – because they can spend this currency with relatively less depreciation in purchasing power, while those who receive the new currency later will be at a disadvantage. This situation is called the “Cantillon effect”.

Kantillon’s observation is more profound than Fisher’s equation because it realizes that the economy has structure and people engage in their activities over time. Increasing the money supply does not evenly distribute new money to everyone according to the existing amount of money, nor does it instantly devalue everyone’s money. Instead, it spreads outward along the structure of the economy and becomes increasingly clear as it spreads. (Do you remember what we said above? The purchasing power of money also varies by region.)

This is the truth about increasing the money supply and depreciating purchasing power – no matter who claims that this process has any benefits, these benefits will not be equally distributed to everyone. Some people may get a lot, while others get nothing – it obviously becomes a source of wealth inequality.

In the era of metal currency, mining metal was costly, and the scale and profits of currency production enterprises were also limited by the market itself – if the profit rate of producing currency was higher than that of other industries, people and capital from other industries would be attracted to the currency manufacturing industry, accelerating the production (devaluation) of money while reducing the profit rate of the industry. This process controlled the quantity of newly issued money. However, in the era of paper currency, such mechanisms disappeared. The lack of market constraints means that the quantity of paper money depends entirely on the mood of the currency issuing authorities, almost as much as they want. This is why the phenomenon of excessive issuance of currency leading to the collapse of purchasing power (“hyperinflation”) is far more common with paper money than with metal currency (such as China in the Yuan Dynasty, China during the Nationalist Party era, present-day Zimbabwe, and Venezuela).

The term “hyperinflation” is very clever, as it seems to imply that some inflation [4] is a good thing. However, this statement is akin to saying that poison can quench thirst.

Next, we need to consider the impact of changes in the quantity of money on another price of money – interest rates – and its market.

Interest Rates, Savings, and Production

Interest rates are used to communicate between suppliers (those with surplus cash willing to lend) and consumers in the lending market. It should be noted that although suppliers and demanders may have different utility evaluations of money, the nature of these utilities is the same for both parties: money can be exchanged for other goods in the market. For suppliers, lending cash means giving up the benefits that cash can bring them – the ability to hedge against risks; for consumers, it means gaining the benefits that cash brings – the ability to immediately obtain the desired goods and services, such as medical care, production equipment, and debt repayment ability.

Here, we are concerned with two phenomena: the separation of “nominal interest rates” and “real interest rates,” and the relationship between interest rates and production.

In the contract between the lender and the borrower, they only specify an interest rate. Translated into English, it is as follows: I am lending you 100 now, and one year later, you should repay me 100 * (1 + i) units. This interest rate i is called the “nominal interest rate”. However, the “real interest rate” obtained by the supplier/borne by the borrower should be (1 + i) * (1 + d) – 1, where d refers to the change in currency purchasing power. This is because the difficulty of repayment for the borrower is not only determined by the agreed nominal interest rate, but also by the change in currency purchasing power itself. If the currency is becoming more difficult to obtain (currency purchasing power increases, d > 0), the burden on the borrower is greater than the nominal amount; if the currency is becoming easier to obtain, the burden on the borrower will be smaller.

Undoubtedly, when negotiating the contract, both the lender and the borrower will have their own estimates of d (which can only be estimated because it has not yet become a reality). This estimate will also be reflected in i. If the lender expects the purchasing power of the currency to decrease, they will naturally increase the nominal interest rate to compensate themselves. But estimation is just estimation. If the actual performance of d deviates from the expectations of both parties during the loan period, the benefits obtained from this contract will also deviate from their expectations.

As mentioned earlier, in summary, there are two forces that affect d: (1) changes in the amount of currency; (2) changes in supply conditions. Technological progress, infrastructure improvement, knowledge accumulation, and improvement in international trade relations will all increase production capacity and make goods cheaper, that is, increase the purchasing power of the currency. Conversely, the deterioration of these conditions will also lead to a decrease in the purchasing power of the currency.

An increase in the amount of currency will cause the purchasing power of the currency to decrease, which will reduce the returns of creditors. This is why we often say that currency issuance is not favorable to creditors, and why kings in history liked to dilute the purity of metallic currency-they could dilute their debt burden by increasing the issuance of currency. Conversely, it will increase the returns of creditors, but it is not favorable to debtors.

However, no matter what, the greater the uncertainty brought by d, the greater the resistance in the loan market. This is why Milton Friedman advocated a fixed rate of currency issuance. Regularly issued currency can minimize the impact of monetary factors on the purchasing power of the currency, thereby reducing resistance in the loan market. A currency with inelastic supply also has this advantage.

On the other hand, interest rates also affect the expansion of production activities. Let’s use an example to illustrate.

Let’s say A is an entrepreneur who finds that he can borrow X units at a nominal interest rate of i, and the loan term is Y. In this Y period, he can use X amount of money to increase production equipment and obtain a monetary income Z at maturity, so that X * (1 – c) ^ Y + Z > X * (1 + i) ^ Y (where c is the depreciation rate of production equipment), that is, if his income during the loan period is sufficient to cover the depreciation of new equipment and the interest on the loan, he will borrow this amount and convert it into production equipment to increase production.

This example can be regarded as a general case of the production process of capital goods (a combination of all resources specifically used for the production of certain products). When Party A uses his own savings as money, it can be considered that he is his own lender – the benefits of increasing production must be greater than the benefits of saving money in order to attract him to implement the production increase plan.

Quantity of Money

We left an unresolved question earlier: what is the quantity of money? Is the quantity of issued currency units the quantity of money when we use a type of paper currency?

Or in other words, our question is: what form of change in the quantity of money will produce the effect mentioned above (the decline in the purchasing power of money)?

This is not a question we raised today, nor is it a question that arose after the Fisher Equation was introduced – after all, people have known for a long time that an increase in the quantity of money leads to its depreciation.

In 19th century Britain, people lived in an era where gold was used as money, but at the same time, major banks also issued their own banknotes (paper currency) that could be used to redeem gold stored in banks. Just like us, people also debated: what exactly counts as money? Does only gold count as money? Does this paper currency that is easier to circulate and can be used to redeem gold not count as money?

Discussing this issue was driven by both policy interest: if these banknotes count as money, should the law also regulate the issuance of these banknotes? But on the other hand, it was also a requirement for academic progress.

Today, we know that in theory, the importance of determining the criteria for money is not in itself, but in relation to other things: what we really want to know is whether, besides the physical cash that we recognize as money – metal coins, paper currency with central bank seals – changes in the quantity of their derivative forms will also produce effects similar to or the same as changes in the quantity of cash?

The answer is, of course. Today, no one would deny that deposits held in banks that can be immediately circulated are also money; fixed-term deposits and money market funds that cannot be immediately circulated are also considered money, although their levels (or monetary nature) are different. There may not necessarily be 100% physical cash backing behind deposits held in banks; under a non-100% reserve system, banks only need to provide a certain proportion of cash as collateral in relation to the amount of deposits; when the bank (within the limits allowed by law) decides to reduce the amount of collateral, it will cause an increase in deposits, resulting in the same effect of an increase in the quantity of money, albeit to varying degrees.

Now, we can return to the arguments against inelastic money.

Stimulating Production or Encouraging Mistakes

Those who support using money to “regulate” the economy do not deny that changes in the quantity of money will affect the purchasing power of money and interest rates. On the contrary, they believe that this impact can be used by them. For example, when the economy enters a downturn, increasing the issuance of money can cause the prices of goods to tend to rise (because the purchasing power of money has decreased, so the nominal prices of goods have risen), and this price increase will make people think it is profitable, thereby encouraging people to resume or increase production; at the same time, when the expansion of money supply causes nominal interest rates to decrease, people will also find that the cost of their risky activities has become lower, which naturally attracts them to increase production.

Both of these claims sound attractive, and even some observable phenomena seem to support them – but in reality, they are both unfounded.

Take the first claim, it actually means that for these producers, the profitability in accounting terms depends entirely on the depreciation of the currency. In other words, if the currency does not depreciate, they cannot observe that the monetary returns from production activities exceed the monetary value of their resource inputs. When they calculate their profits at the end of the period, if they take into account the depreciation of the currency’s purchasing power, they may find that they not only have no profits, but actually incur losses, or in other words, they would be better off not engaging in production activities. Here, the depreciating currency actually creates an illusion, adding noise to market activities and hindering people from forming new production-consumption structures under new conditions. The so-called economic downturn is actually people spontaneously moving towards this new structure.

The same applies to the operation of increasing the currency supply to lower the nominal interest rates in the market. In a fiat currency system, increasing the currency supply is easy, thus lowering the nominal interest rates for borrowing and lending becomes easy as well. However, people forget that it is real savings in terms of tangible resources, not the quantity of money, that supports production expansion. During the period of capital formation, these intermediate goods actually do not bring any benefits to people, and they also require people to continuously add resources to transform into something with real production capacity. The artificially lowered nominal interest rates are just the opposite: when the nominal interest rates decrease, people will perceive that the benefits of monetary savings decrease, so they will increase consumption and deplete current finished goods. On one hand, people increase consumption and demand producers to produce things they need immediately; on the other hand, increasing capital goods requires producers to produce things that will be useful in the future, namely things that can be combined to create capital goods, rather than consumer goods that people need. The function of the interest rate market itself is to coordinate the production of both, but nowadays, the deliberately lowered nominal interest rates transmit incorrect signals. The expanding demand for both consumer goods and capital goods contradicts each other, and one day, those who have set investment plans will find that the prices of the required resources are rising rapidly – or in other words, there are not enough real savings available – making it impossible to complete the investment. But if investments cannot be completed, they are meaningless. It means the complete bankruptcy of the investment plan.

The only support for this stimulus theory is that it seems difficult to find errors in statistics – currency expansion can indeed lead to an increase in statistics such as GDP. This can be seen from the Fisher equation – the right side of the equation is similar to the concept of “Gross Domestic Product” in statistics: the total value of market exchanges that occur within a certain period of time, a certain region (or group). However, GDP is just a number, it does not measure the benefits people obtain from the market, and these benefits cannot be measured – when someone spends 10 dollars on a bunch of grapes, no one knows how much happiness they derive from this bunch of grapes, and how much more happiness they could have obtained with the same amount of money. The stability of the GDP number does not mean that people have gained benefits or that a rational production-consumption structure has been formed. Perhaps it is just postponing the outbreak of the crisis rather than eliminating it.

The theory of contracting currency will also have the same problems.

All ideas that require “on-demand” changes in the quantity of currency are demanding arbitrary power that surpasses all market participants. They can arbitrarily dilute others’ wealth and create obstacles to spontaneous transactions without any responsibility.

Leakage of Currency

This point doesn’t really need much discussion. The reason why metallic currencies are superior to previous currencies is that they are easier to divide, making it easier to obtain smaller currency units. Bitcoin has the same characteristics. In addition, it is also possible to meet people’s cash needs by speeding up the circulation of currency, which is something that technological progress can achieve.

Summary

We have analyzed the impact of changes in the quantity of currency to determine if a currency with “elastic supply” can really bring benefits to people. The result is that, at least for now, the arguments put forward by the proponents of elastic supply, especially the “stimulus theory,” do not hold up. Moreover, they also bring many problems. These problems are more real and destructive than the benefits proposed by supporters of elastic currency.

The “shortage” caused by currency leakage can be mitigated even though it has problems. You can think of the various “scalability” solutions that have emerged in the Bitcoin world as addressing this problem.

For some, Bitcoin’s monetary policy may be considered bold, but for others, it reflects centuries of human contemplation on the issue of currency.

We will continue to update Blocking; if you have any questions or suggestions, please contact us!

Was this article helpful?

93 out of 132 found this helpful

Related articles

- Rollup 2.0 The Battle of Decentralized Sorters

- Looking ahead Lightning Payment in 2025

- Security Monthly Report | Stay Vigilant! The total losses caused by hacker attacks and other factors in the Web3 ecosystem in September exceeded $360 million!

- An analysis of three concepts related to Lagrange products State Proof, Lagrange Committee, and ZK Big Data.

- From the discussion of the Friend.Tech fork, what other use cases does SocialFi have?

- Playing with deception Overseas version of ‘Miao Ya’ BeFake goes viral worldwide

- Anthropic, which has seen a skyrocketing valuation, has become FTX’s biggest hope for debt repayment.