Analysis of SEC’s Cryptocurrency War Trigger and 5 Possible Endings

Analysis of SEC's Cryptocurrency War Trigger and Possible OutcomesAuthor: Matt Levine Translation: jk, Odaily Star Daily

Editor’s note: This article was written after the US Securities and Exchange Commission sued Binance; one of the fundamental differences between the SEC and Binance, and the core argument discussed in this article, is whether cryptocurrency is a security. If it is a security, then Binance and all other exchanges operating in the United States must register securities provided to investors with the SEC. If it is not a security, there is no need to register. Currently, all exchanges operating in the United States have not registered with the SEC. Therefore, if the court rules that tokens are securities, the SEC will win, and vice versa.

US SEC sues Crypto leader

“There is now a basic standard that all cryptocurrency exchanges are committing crimes, if you are lucky, the exchange you use is only committing crimes in the program (rather than in the result).” Why? Examples are as follows:

Is your exchange operating an illegal securities exchange in the United States? Yes! It really is! At least, according to the SEC’s view, every cryptocurrency exchange in the United States is illegal. You may not agree with this viewpoint-many executives of cryptocurrency exchanges do not agree, and we will discuss these arguments in detail below-but from a realistic perspective, if you are trading cryptocurrency, you are not fully complying with US securities laws.

- HOLD Cave: The Story of Bitcoin’s Growth Amidst Volatility

- Long push: Data tells you whether the NFT market is about to start a new bull market

- What are the highlights of GBRC-721 compared to BRC721?

Is your exchange stealing customer funds? Maybe! Some are, but some are not. If you are a customer, this is the issue you should be most concerned about.

Operating an illegal securities exchange and stealing customer funds are related, but these are two different things. “Oh, I shouldn’t entrust my money to those who violate US law”: Of course, yes, this is a reasonable position that can help you avoid many cryptocurrency disasters, but it will also make you unable to trade cryptocurrency at all. This is your choice!

I have exaggerated the principle interpretation of all this a bit-but not too much.

Yesterday, the US Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC) sued Binance, the world’s largest cryptocurrency exchange, and its founder Zhao Changpeng, accusing them of operating an illegal securities exchange. Today, the SEC also filed a lawsuit against Coinbase Inc., the largest cryptocurrency exchange in the United States, for operating an illegal securities exchange.

There are basically two ways in which a cryptocurrency exchange can get into trouble with the SEC. One good way is to operate an illegal securities exchange (i.e. offering unregistered securities). In April of this year, the SEC filed a lawsuit against Bittrex Inc. for allegedly operating an illegal securities exchange; any reasonable interpretation of the Bittrex case can make it clear that similar cases may be brought against Coinbase and Binance. In the SEC’s view, every cryptocurrency exchange in the U.S. is illegal.

Another bad way is to get into trouble for stealing customer funds. In December of last year, the SEC filed a lawsuit against a major cryptocurrency exchange, FTX Trading Ltd. This is the SEC’s charge against FTX. I can say with great confidence that the SEC does believe that FTX is indeed operating an illegal securities exchange in the U.S. But this was not mentioned in the indictment – because there were too many other issues to deal with. FTX allegedly stole all of its customers’ funds; when an exchange steals funds, the SEC focuses on this. When not all funds are stolen, the SEC focuses on the issue of illegal securities exchanges.

Therefore, for these cases this week, one question is: Did the SEC sue Coinbase and Binance because they are cryptocurrency exchanges, or because they are evil cryptocurrency exchanges? Are the charges here “you allow people to trade cryptocurrencies, which we think is illegal”, or “you attract people to trade cryptocurrencies and steal their capital”?

For Coinbase, I think the answer is obvious. Relative to other cryptocurrency exchanges, Coinbase is very compliant. It is a publicly traded U.S. company registered in Delaware and listed on Nasdaq. It went public in 2021, submitting detailed disclosure documents to the SEC. Its financial statements are audited by Deloitte. Its business model seems to be to receive funds from customers, use these funds to purchase cryptocurrency, and securely store the cryptocurrency in an account named after the customer. I dare not make any bold statements about any cryptocurrency participant, and I have made mistakes in the past, but I don’t think Coinbase has stolen its customers’ funds.

In fact, the SEC’s charges against Coinbase are very boring and are fully focused on the fact that Coinbase is not registered as a securities exchange. Again, every cryptocurrency exchange violates U.S. securities laws in the SEC’s view. But relatively speaking, Coinbase’s violations are polite and relatively harmless. Not completely harmless – the SEC says, “Coinbase’s unregistered conduct deprives investors of important protections, including SEC oversight, recordkeeping requirements, and safeguards against conflicts of interest.” But the impact is relatively small.

As for Binance, the answer is more interesting. As a cryptocurrency exchange, Binance has a little bit of skill in complying with the law, but not much—it is known for its non-transparency, uncertain headquarters location, and aim to avoid convoluted regulatory networks. (“We never want [Binance] to be supervised,” said its chief compliance officer in 2018, according to the SEC.) Like FTX, it has its own token—BNB; it has its own affiliated trading companies; and it provides separate platforms for U.S. customers (Binance.us) and customers in the rest of the world (Binance.com). It was sued by the U.S. Commodity Futures Trading Commission in March, primarily for allowing large U.S. clients (such as high-frequency market makers Jane Street and Tower Research) to trade on its Binance.com exchange via its offshore affiliate and mentioning the issue of terrorist funding sources in the CFTC’s complaint.

Similarly, the SEC’s charges against Binance allege that it caught some evidence of improper conduct by Binance. Binance has some affiliated market makers, including Sigma Chain AG and Merit Peak Ltd., companies allegedly controlled by Changpeng Zhao, that trade on Binance’s Binance.com and Binance.us. The SEC suggests that they engage in suspicious activities:

For example, by 2021, at least $145 million flowed from BAM Trading (i.e. Binance.us) into Sigma Chain accounts, and another $45 million flowed from BAM Trading’s Trust ComBlockingny B account into Sigma Chain accounts. Sigma Chain spent $11 million from that account to buy a yacht. (For implication only, there is no actual evidence.)

Moreover, from September 2019 to June 2022, Sigma Chain AG, owned and controlled by Zhao Changpeng, conducted wash trading, artificially inflating the trading volume of crypto asset securities on Binance’s US platform.

In addition, the SEC alleges that Changpeng Zhao and Binance exercise control over customer assets on the platform, allowing them to commingle customer assets or transfer customer assets at will, including to Sigma Chain, owned and controlled by Zhao Changpeng.

However, the SEC did not emphasize these charges too much, most of Binance’s charges are the same as Coinbase’s charges: Binance is accused of operating a cryptocurrency exchange that allows and lists some cryptocurrencies deemed securities for U.S. customers without registering as a U.S. securities exchange. I tend to see yesterday’s lawsuit as an endorsement of Binance by the SEC. The SEC, as well as the previous CFTC, conducted a thorough investigation of Binance and wrote a 136-page complaint (Odaily Star Daily’s in-depth analysis of the complaint) but the only issue they could find was that Binance was just operating a cryptocurrency exchange.

Although the arguments in the two complaints are largely the same, Coinbase and Binance have taken very different attitudes. The key legal issue (which we will discuss below) is whether the cryptocurrency tokens listed on Binance and Coinbase are securities. If they are deemed to be securities, then it is likely that Coinbase and Binance (as well as Bittrex and all other exchanges) are operating illegal securities exchanges; if they are not securities, then everything is fine. Coinbase is aware of this potential risk and has established a committee and related procedures to consider and mitigate this risk. A description from the SEC’s charges against Coinbase reads:

Given that at least some digital assets were offered, sold, and distributed by identifiable groups of people or promoters, Coinbase publicly released the “Coinbase Digital Asset Framework” in or around September 2018, which included an application form for digital asset issuers and promoters to apply to list their digital assets on the Coinbase platform.

Coinbase’s listing application requires issuers and promoters to provide information about their digital assets and blockchain projects. It specifically requires information related to the Howey analysis of digital assets.

In addition, in or around September 2019, Coinbase and other digital asset businesses founded the “Crypto Rating Council” (CRC). The CRC subsequently published a framework for analyzing digital assets that “distills a set of concise yes-or-no questions designed to provide clear answers to the four elements of the Howey test” and assigns digital assets a score from 1 to 5, with 1 indicating “the asset has few or no features that are consistent with investment securities” and 5 indicating “the asset has many features strongly consistent with investment securities.”

Upon announcing the formation of the CRC, Coinbase stated, “While the SEC has issued helpful guidance, determining whether any given digital asset is a security ultimately requires a fact-based analysis.” (Meaning, it ultimately depends on the views of the SEC and the courts.)

Very responsible, right? Nevertheless, the SEC disagrees with Coinbase’s conclusion and has some objections to its process:

During the period from late 2019 through the end of 2020, the number of digital assets traded on the Coinbase platform increased by more than double, and increased by more than double again in 2021. During this period, Coinbase listed digital assets on the Coinbase platform that scored highly under the CRC framework. In other words, Coinbase made strategic business decisions to add these digital assets to the Coinbase platform, even though it recognized that these digital assets had features of securities, in order to achieve exponential growth of the Coinbase platform and increase its trading profits.

Meanwhile, here’s Binance’s “stellar” compliance chief’s description of Binance’s fact-based analysis of whether Binance is listing security tokens in the United States:

As Binance’s compliance chief candidly admitted to another Binance compliance person in December 2018, “We’re running a TMD unlicensed securities exchange in the U.S., bro.”

How clear is that! Coinbase has hired a lot of lawyers, done a lot of analysis, and written a lot of checklists to convince itself that it can legally operate a cryptocurrency exchange in the United States. Binance’s attitude is “it might be illegal in the U.S., meh.” The SEC completely agrees with Binance’s point of view (that both are illegal).

This may be good news for Coinbase: it may be able to present itself in court as a good-faith actor trying to comply with the law, while Binance looks like a bad-faith actor trying to flout the law; Coinbase may win in litigation with the SEC, while Binance may lose. But I have to say, so far, Binance’s approach seems wiser. Binance noticed that operating a cryptocurrency exchange in the U.S. was likely illegal, but did it anyway, but it minimized and segmented its risks in the U.S. as much as possible: its U.S. customers were relatively small and it seemed to put most of its business outside the U.S. Coinbase, on the other hand, has tried its hardest to operate a legal and regulatory-compliant cryptocurrency exchange in the U.S., and now the SEC says that’s impossible. If the SEC is right, what’s left for Coinbase’s business?

What is a Security, Anyway?

Okay, let’s talk about the basic theory that the SEC is putting forward here, which we discussed when the SEC sued Bittrex:

1. If you operate an exchange that offers securities trading in the U.S., you need to register with the SEC as a securities exchange.

2. The cryptocurrency tokens that Binance and Coinbase offer are securities.

3. They haven’t registered their exchanges as securities exchanges in the U.S.

4. Bad!

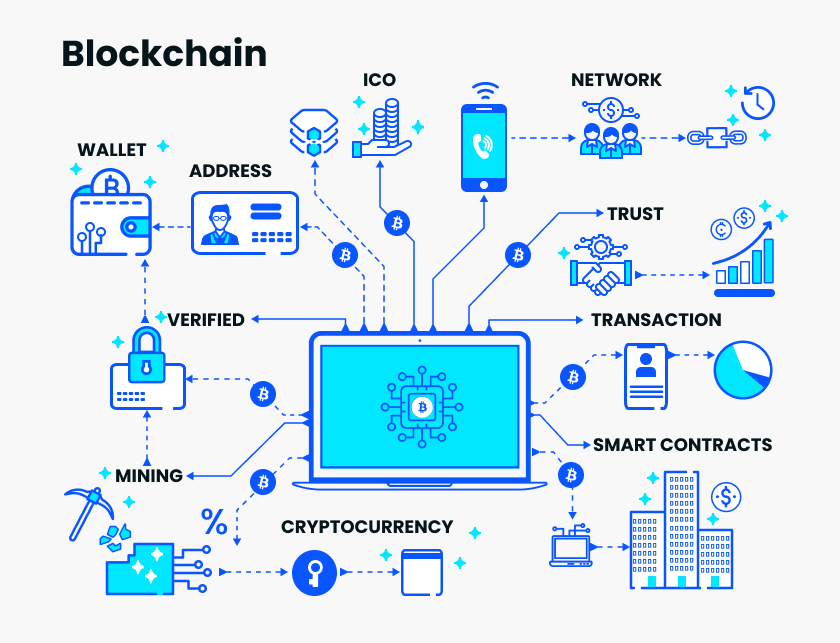

The first point is a bit more complicated than it sounds; for example, there are some stock trading venues that aren’t registered as securities exchanges, they’re registered as other kinds of organizations under different rules. But from the SEC’s point of view, what’s important is that the rules of securities exchanges protect investors. In particular, they often require three key functions to be separated, which are often combined in cryptocurrencies, including an exchange that matches buyers and sellers, brokers/dealers who represent customers trading on the exchange, and clearinghouses that actually move the funds and securities. In the stock market, you can place an order on Robinhood’s website to buy a stock on the New York Stock Exchange, and the Depository Trust Co. holds the stock and settles the trade. In the cryptocurrency market, you can place an order on Coinbase’s website to buy cryptocurrency on Coinbase, and Coinbase holds the cryptocurrency and settles the trade.

However, the focus here is on the third point: are encrypted tokens considered securities? The SEC’s basic view is that most encrypted tokens – not all, not including Bitcoin, but most – are securities under US law. Coinbase clearly believes that many of them are not securities. The specific issue in dispute here is whether a series of popular encrypted tokens, including SOL of Solana, ADA of Cardano, MATIC of Polygon, FIL of Filecoin, MANA of Decentraland, ALGO of Algorand, AXS of Axie Infinity, and VGX of Voyager Digital, are listed as securities, and the SEC mentions that they have been listed on Binance and/or Coinbase.

US securities laws define “securities” to include, but not limited to, “stocks”, “equity or share certificates of profit-sharing agreements”, “pre-established certificates or subscription certificates”, “transferable shares, investment contracts, [or] voting trust certificates”. The most commonly used term is “investment contract”, which was interpreted by the US Supreme Court in the famous 1946 case SEC v. W.J. Howey Co.

According to the “Securities Law”, an investment contract refers to a contract, transaction or plan in which individuals invest funds in a joint venture and expect to obtain profits purely through the efforts of the initiator or third party, whether the shares of the enterprise are represented by formal certificates or nominal equity certificates in physical assets. This definition… makes it possible to require “full and fair disclosure of the numerous tools that are part of the common concept of securities in our business world for legal purposes”, and it reflects a flexible rather than static principle that can adapt to the countless and varied schemes designed for those seeking to use other people’s funds to obtain profits through the commitment of others.

Investors provide capital and share in the revenue and profits, while initiators manage, control and operate the enterprise. Therefore, regardless of the specific arrangement of these investors’ interests in legal terms, it involves an investment contract.

The key is whether the scheme involves investment funds in a joint venture and whether the profits come entirely from the efforts of others. If this test is satisfied, it is irrelevant whether the enterprise is speculative or non-speculative or whether there is a sale of property with or without intrinsic value.

This creates the “Howey test”, in which the court asks whether the following conditions exist: (1) investment funds; (2) joint ventures; (3) expected profits; and (4) whether profits come entirely from the efforts of others. The SEC has maintained since 2017 that most encrypted enterprises meet this description.

Using Solana as an example, Solana is a blockchain that runs encrypted applications, and its native token is called SOL. The following is the SEC’s explanation of Solana:

“SOL” is the native token of the Solana blockchain. The Solana blockchain was created by Solana Labs, Inc. (hereinafter referred to as Solana Labs). Solana Labs is a Delaware-based company headquartered in San Francisco, founded by Anatoly Yakovenko (hereinafter referred to as Yakovenko) and Raj Gokal (current CEO and COO of Solana Labs) in 2018. According to Solana’s website www.solana.com, the Solana blockchain is a network that can build decentralized applications (dApps), composed of a platform that aims to improve blockchain scalability and achieve high transaction speed, adopting a combination of consensus mechanisms.

According to Solana’s website, SOL can be “pledged” on the Solana blockchain to earn rewards, and when a transaction is made on the Solana blockchain, a small amount of SOL must be “destroyed”. This is a common function of native tokens on the blockchain, which is used to avoid potential bad actors from “clogging” a blockchain with an infinite number of proposed transactions through cryptographic distributed ledgers.

Solana Labs sells SOL tokens to raise funds for building the Solana ecosystem:

Solana Labs publicly stated that it will collect the proceeds from private and public SOL sales into its controlled comprehensive cryptographic asset wallet, and use these funds for the development, operation, and marketing of the Solana blockchain to attract more users to use the blockchain (because people who want to interact with the Solana blockchain need to provide SOL, which may increase the demand and value of SOL itself). For example, when selling private SOL in 2021, Solana Labs publicly stated that it will use investors’ funds to: (i) hire engineers and support staff to help develop Solana’s developer ecosystem; (ii) “accelerate the launch of market-ready applications that bring billions of users into the cryptocurrency field”; (iii) “launch an incubation studio to accelerate the development of decentralized applications and platforms on Solana”; and (iv) establish a “risk investment department” and “trading department” dedicated to the Solana ecosystem.

Howey Test:

1. Has the investor invested funds? Yes, SOL tokens are sold in currency form to raise funds for the construction of Solana.

2. Is there a joint venture? Yes, Solana is a company; it is a blockchain ecosystem competing with Ethereum, Cardano and others, aimed at attracting users.

3. Is there an expected profit? Yes, people buy SOL hoping that its price will go up, and it has actually gone up.

4. Is the profit coming from the efforts of others? Yes, the increase in SOL’s price is due to its promoters and developers making Solana into a popular blockchain, increasing demand for SOL.

These are typically difficult questions to judge. Most large crypto blockchains are to some extent decentralized; Solana’s growth depends not just on Solana Labs’ efforts, but also on the efforts of third-party users and developers who like using it. For some crypto tokens, it can be reasonably argued that people are buying the tokens not as an investment with profit expectations, but to use them for transactions on the blockchain; SOL tokens are the “fuel” people use to run programs and make transactions on the Solana blockchain, and if purchased purely as a “utility token,” it could be argued that it is not a security. Most crypto tokens have both utility value and speculative investment characteristics, making analysis complicated.

Moreover, even if you are purchasing SOL as a speculative investment, it is unclear whether you are buying it to share in the profits of the underlying enterprise. Your thought process might be “If I buy SOL, lots of other people might buy SOL, its price will go up, and I can make money.” This is not an expectation of profit from “the efforts of others”; it is an expectation of profit from speculation and memes. We talked about Dogecoin yesterday, which is a jokey crypto token with people openly pledging not to take any action to build an ecosystem; people buy Dogecoin because they believe other people will buy Dogecoin. I personally think this means Dogecoin is not a security; a token that is pure nonsense involving “the efforts of others” is not enough to meet the criteria. (There’s no doubt that, say, Beanie Babies stuffed animals are not securities.) And even in crypto projects that do promise effort, an ecosystem, and hard-working, clever developers, many people’s pure reasons for buying the token may be the same as the reasons they buy Dogecoin: for the numbers to go up.

But I like to think of the relationship between crypto and securities as most crypto tokens being obviously similar in some way to stocks of some kind of basic tech business. In Solana (and Cardano, Polygon, etc.), the underlying business is a platform-type business for building blockchain ecosystems of applications, primarily financial services applications, primarily for trading cryptocurrencies. Everyone who buys these tokens is in some loose sense a quasi-shareholder of that business. They get returns in the same way as traditional shareholders: stock buybacks. What is called stock buybacks in crypto terms is referred to as “burning.”

Additionally, Solana Labs promotes its “burning” of SOL tokens as part of its “deflationary model.” As Yakovenko explained in an article titled “Solana (SOL): Extending Cryptocurrencies to the Masses” published on gemini.com on April 14, 2021, “Solana’s transaction fees are paid in SOL and reduced through burning (or permanent destruction) as a deflationary mechanism to decrease total supply and thereby maintain a healthy SOL price.” As explained on the Solana website, the “current total supply” of SOL has been reduced through burning of transaction fees and planned token reduction activities since the launch of the Solana network. This promotion of the burning of SOL as part of the “deflationary mechanism” of the Solana network gives investors reason to believe that their purchase of SOL has profit potential, as the built-in mechanism can reduce the supply and thus increase the price of SOL.

In the lawsuit against Binance, the US Securities and Exchange Commission quoted Zhao Changpeng’s description of Binance’s own BNB token burning mechanism:

In fact, in an interview posted on YouTube on July 9, 2019, Zhao Changpeng described Binance’s planned BNB burning, stating, “The benefit we promised in the white paper is that every quarter we will use 20% of our profits to buy back [BNB] at market value… We will buy back and burn these tokens. We will burn up to 100 million BNB. Basically, it’s half of all available tokens… Financially, it’s the same as dividends in the same way.”

I mean, I would say it works the same way as stock buybacks, but of course dividends and stock buybacks are essentially equivalent. The key is that in crypto projects, shareholders (sorry, token holders) share in the profits of the project when a portion of the revenue is used to buy back and burn tokens, thus increasing the value of the remaining tokens, in the same way as stock buybacks.

One way to understand cryptoeconomics is that cryptocurrency constructs a new way to sell the promise of a promising technology and financial enterprise without calling it a stock. For example, if you are starting a cryptocurrency exchange and want to raise money, you can offer investors the stock of your company. If the business operates well and there is a large profit (from transaction fees charged to customers), you will share these profits with investors. However, there are some problems:

1. If you sell stocks to the public, you will need to register with the SEC.

2. If you sell stocks to large venture capitalists, they will need to register for resale with the SEC or find an exemption from SEC registration in some other way.

3. In any case, you may need to provide some kind of financial information about the business to get funding.

4. Shareholders may want voting rights, ongoing financial disclosure, etc., which are customary and often legally required.

Alternatively, if you are starting a cryptocurrency exchange, you can go to investors and offer them tokens in your business. If the business operates well and there is a large profit (from transaction fees charged to customers), you will share these profits with investors (by buying and destroying tokens). This is great:

1. If you sell tokens to the public, you can declare that they are not securities and do not need to register with the SEC.

2. If you sell tokens to large venture capitalists, they can declare that these tokens are not securities and are freely resold.

3. You will write a white paper to sell tokens, which does not necessarily need to include a lot of financial or operational details.

4. You can give tokens any rights you want.

I may be a bit unfair. I am describing a pure regulatory arbitrage; Binance’s BNB token or FTX’s FTT token is simply a substitute for stocks, issued by a company to raise funds needed to operate centralized business. Many cryptocurrency projects are not completely like this; in some projects, people are full of idealism to establish a decentralized ecosystem that does not belong to any company. Selling tokens can become a way to create and fund ownerless projects, and this economic model is really different from the company owned by shareholders. But in many cases, the cryptocurrency ecosystem seems to be built by a fairly centralized team, and tokens are seen as stocks of a promising new technology company, started by a promising team.

You can see why cryptocurrency enthusiasts love this! It combines regulatory arbitrage with exciting philosophical novelty. You can also see why the SEC doesn’t like this situation! The SEC is very familiar with “the myriad and diverse schemes seeking to use other people’s money for the promise of profits.” The SEC is the regulatory agency that is circumvented in arbitrage. And it clearly doesn’t like that.

What happens after the SEC lawsuit?

Here are a few possible outcomes:

1. The SEC wins, and cryptocurrencies are more or less banned in the United States. Bitcoin, Ethereum, and possibly Dogecoin can still be purchased in the US because they are not securities, but any other crypto project may be deemed a security and cannot be traded in the US. Cryptocurrencies gradually decline and die out, and people turn to artificial intelligence. The SEC kills cryptocurrency in a slow revengeful way because cryptocurrency tries to circumvent SEC regulation.

2. The same scenario, but cryptocurrencies thrive elsewhere while the US misses out. Cryptocurrencies are proven to have great transformative and monetary value, and the US is left behind in the competition. Or cryptocurrencies are proven to be a weird niche financial product that can be traded in Europe but not in the US, like binary options or CFDs. Either way, cryptocurrencies continue abroad but cannot develop in the US.

3. The SEC wins, and then some existing crypto companies, new crypto entrants, and traditional financial services companies jointly find a way to comply with US securities law for cryptocurrency trading. Everyone will try their best, saying “OK, Solana will start submitting annual reports and audited financial statements,” and people will establish cryptocurrency exchanges registered with the SEC, separated from clearing houses and brokerages, and so on. This seems very difficult because the SEC is obviously not interested in any crypto project. I’m not going to sit here and tell you “how crypto companies can register their tokens as securities.” No doubt, Coinbase has been trying to figure out how to do this, and they keep “harassing” the SEC for permissive regulations, but so far, luck hasn’t been on their side. But I think this is also possible.

4. The SEC failed, and the court said “What, no, none of this is securities,” and cryptocurrencies continue to trade in the US with little securities regulation.

5. Congress (or a future SEC) intervenes to change the rules, saying “Of course, under existing law, all of this is technically illegal, but stifling such innovation is crazy, so we’ll create new regulations to allow regulated trading of cryptocurrencies in the US.”

I don’t know which outcome will happen. The last outcome is what the cryptocurrency industry is hoping for, and Congress seems to have some interest in creating cryptocurrency rules.

But what I want to say is that the SEC is clearly betting on the first outcome. That’s why, after the collapse of FTX and many other large cryptocurrency companies, after cryptocurrency prices fell, and after venture capitalists turned to artificial intelligence, these cases are being brought now. These cases are high-risk cases for Binance and Coinbase: Coinbase and Bitcoin are large companies with ample funding, excellent lawyers, and lobbying teams. They have the resources and motivation to fight to the end, and they do have fairly good legal arguments. The SEC might lose! But it is strategically maximizing its chances of winning. I wrote in February:

When cryptocurrencies are popular, exciting, and continually rising, if you are a regulatory agency that says “no, we must stop this,” you look like a killjoy. Investors want to put their money into something that is going up, and you are preventing them from doing so, making them angry. Politicians like things that are going up and hold hearings about how you are stifling innovation. Cryptocurrency founders are wealthy and popular, criticizing you on Twitter and getting lots of likes and retweets. Your own regulators are also looking for their next job in the private sector, hoping to be leaders in cryptocurrency innovation rather than just banning everything.

When cryptocurrencies fall, and many projects disappear in fraud and bankruptcy, you can say “I told you so (this was a scam).” At that time, people are more willing to regulate, or even ban everything outright. The founder of a bankrupt cryptocurrency company that has been sued can say “you stifled innovation,” but no one cares.

This is the bet that the SEC is making right now. We’ll see if this bet is right.

We will continue to update Blocking; if you have any questions or suggestions, please contact us!

Was this article helpful?

93 out of 132 found this helpful

Related articles

- Why SEC Chairman Gary Gensler is Cracking Down on the Crypto Market: Latest Speech

- Metaverse Investment: Opportunities and Risks in the Trillion-dollar VR Market

- ZK Co-Processor: Further Opens up the Verifiable Computing Market

- On-chain data analysis: Are we on the brink of the next NFT bull market?

- Amid the era of encrypted regulation, the United States is falling behind.

- Is the Bitcoin ecosystem a flash in the pan or brewing for a bigger explosion? BRC-20 has seen a roller coaster trend.

- Galaxy Digital: How is MEV currently being distributed among participants and who will capture MEV in the future?