The Economist Old Article How did Bitcoin become a Trust Machine?

The Economist - How Bitcoin Became a Trust MachineGary Gensler once said that the current crypto world is like the “wild west”, but we don’t have to overlook the pioneering spirit, autonomy, adventure, and innovation that the “westward movement” brought to that era just because there are many outlaws in the west. Just like Bitcoin, which emerged in 2008, it is bringing various changes to this society and this world.

Below is a compilation of an article about Bitcoin from The Economist in 2015 – The Trust Machine, which serves as a comparison of the status of the Bitcoin/blockchain industry over two 7-year periods. This will help us realize that despite being in the midst of the crypto winter today, the faith, freedom, and passion of the past still remain.

Below, enjoy:

- MicroStrategy’s latest holding of $4.5 billion in Bitcoin exposed, these eight Chinese listed companies also boldly bet on encrypted assets

- Can the presidential candidate’s stance on Bitcoin make Argentina the next El Salvador?

- LianGuai Morning Post | Europe’s First Spot Bitcoin ETF Listed, Embedded with Renewable Energy Certificates

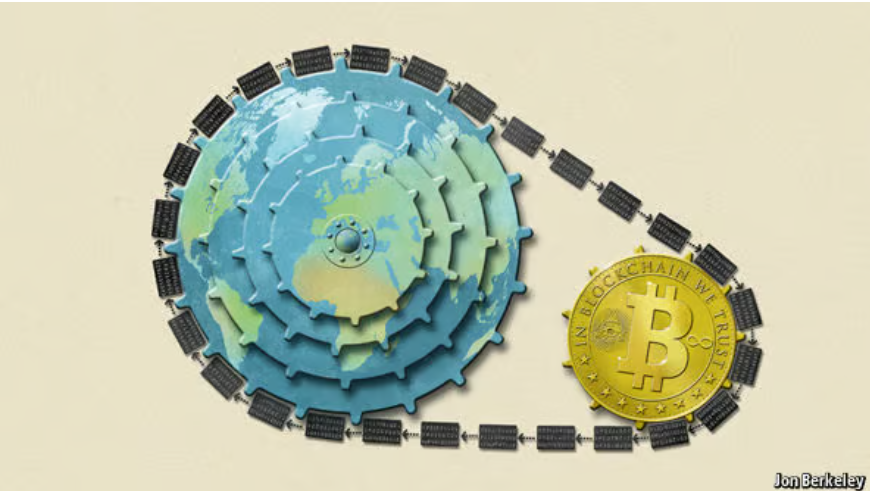

The technology behind bitcoin could transform how the economy works.

The technology behind bitcoin could transform how the economy works.

Oct 31st 2015

BITCOIN has a bad reputation. The decentralised digital cryptocurrency, powered by a vast computer network, is notorious for the wild fluctuations in its value, the zeal of its supporters and its degenerate uses, such as extortion, buying drugs and hiring hitmen in the online bazaars of the “dark net”.

Bitcoin has always had a notorious reputation. This decentralised digital cryptocurrency, powered by a vast computer network, is known for its drastic fluctuations in value, the fanaticism of its believers, and its degenerate illegal uses, such as buying drugs and hiring hitmen on the “dark net” online marketplaces.

This is unfair. The value of a bitcoin has been pretty stable, at around $250, for most of this year. Among regulators and financial institutions, scepticism has given way to enthusiasm (the European Union recently recognised it as a currency). But most unfair of all is that bitcoin’s shady image causes people to overlook the extraordinary potential of the “blockchain”, the technology that underpins it. This innovation carries a significance stretching far beyond cryptocurrency. The blockchain lets people who have no particular confidence in each other collaborate without having to go through a neutral central authority. Simply put, it is a machine for creating trust.

This is unfair. The value of a bitcoin has been pretty stable, at around $250, for most of this year. Among regulators and financial institutions, skepticism has given way to enthusiasm (the European Union recently recognized it as a currency). But most unfair of all is that bitcoin’s shady image causes people to overlook the extraordinary potential of the “blockchain”, the technology that underpins it. This innovation carries a significance stretching far beyond cryptocurrency. The blockchain lets people who have no particular confidence in each other collaborate without having to go through a neutral central authority. Simply put, it is a machine for creating trust.

The origin of the blockchain (The blockchain food chain)

To understand the power of blockchain systems, and the things they can do, it is important to distinguish between three things that are commonly muddled up, namely the bitcoin currency, the specific blockchain that underpins it and the idea of blockchains in general. A helpful analogy is with Napster, the pioneering but illegal “peer-to-peer” file-sharing service that went online in 1999, providing free access to millions of music tracks. Napster itself was swiftly shut down, but it inspired a host of other peer-to-peer services. Many of these were also used for pirating music and films. Yet despite its dubious origins, peer-to-peer technology found legitimate uses, powering internet startups such as Skype (for telephony) and Spotify (for music streaming)—and also, as it happens, bitcoin.

In order to understand the functionality of blockchain, as well as the capabilities it can achieve, it is necessary to distinguish between three often confused concepts: the Bitcoin currency itself, the blockchain technology that supports the Bitcoin network, and the overall concept of blockchain. A useful analogy is Napster, which was launched in 1999 as a groundbreaking but illegal peer-to-peer file-sharing service network, providing free access to millions of music tracks. Napster itself was quickly shut down, but it inspired many other peer-to-peer service networks, many of which were also used for pirating music and movies.

Although the original intention of the above peer-to-peer service networks is debatable, the technology later found legitimate uses, providing momentum and direction for internet startups (such as Skype for telephone and Spotify for music streaming), and the same applies to Bitcoin.

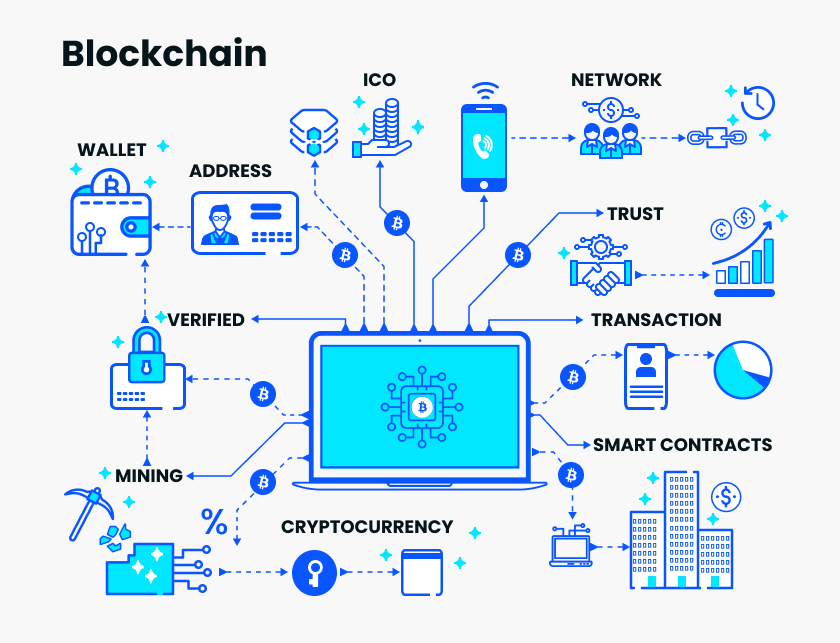

The blockchain is an even more potent technology. In essence, it is a shared, trusted, public ledger that everyone can inspect, but which no single user controls. The participants in a blockchain system collectively keep the ledger up to date: it can be amended only according to strict rules and by general agreement. Bitcoin’s blockchain ledger prevents double-spending and keeps track of transactions continuously. It is what makes possible a currency without a central bank.

Blockchains are also the latest example of the unexpected fruits of cryptography. Mathematical scrambling is used to boil down an original piece of information into a code, known as a hash. Any attempt to tamper with any part of the blockchain is apparent immediately—because the new hash will not match the old ones. In this way, a science that keeps information secret (vital for encrypting messages and online shopping and banking) is, paradoxically, also a tool for open dealing.

Bitcoin itself may never be more than a curiosity. However, blockchains have a host of other uses because they meet the need for a trustworthy record, something vital for transactions of every sort. Dozens of startups now hope to capitalize on the blockchain technology, either by doing clever things with the bitcoin blockchain or by creating new blockchains of their own.

One idea, for example, is to make cheap, tamper-proof public databases—land registries, say, (Honduras and Greece are interested); or registers of the ownership of luxury goods or works of art. Documents can be notarised by embedding information about them into a public blockchain—and you will no longer need a notary to vouch for them. Financial-services firms are contemplating using blockchains as a record of who owns what instead of having a series of internal ledgers. A trusted private ledger removes the need for reconciling each transaction with a counterparty, it is fast and it minimises errors. Santander reckons that it could save banks up to $20 billion a year by 2022. Twenty-five banks have just joined a blockchain startup, called R3 CEV, to develop common standards, and NASDAQ is about to start using the technology to record trading in securities of private companies.

For example, one idea is to create low-cost, tamper-proof public databases, such as land registries (Honduras and Greece are interested), or registers of ownership for luxury goods or works of art. The aforementioned idea can be notarized by embedding information about the subject matter into a public blockchain, eliminating the need for a notary to provide witness. Financial service companies are considering using blockchain as a record of who owns what, instead of having a series of internal ledgers.

A trusted private distributed ledger eliminates the need to reconcile each transaction with the counterparty. It is efficient and error-free. Santander Bank believes that by 2022, it can save banks up to $20 billion in costs. Twenty-five banks have just joined a blockchain startup called R3 CEV to establish common standards, and NASDAQ is about to start using this technology to record transactions of securities of private companies.

These new blockchains need not work in exactly the way that bitcoin’s does. Many of them could tweak its model by, for example, finding alternatives to its energy-intensive “mining” process, which rewards newly minted bitcoins in return for providing the computing power needed to maintain the ledger. A group of vetted participants within an industry might instead agree to join a private blockchain, say, that needs less security. Blockchains can also implement business rules, such as transactions that take place only if two or more parties endorse them, or if another transaction has been completed first. As with Napster and peer-to-peer technology, a clever idea is being modified and improved. In the process, it is fast throwing off its reputation for shadiness.

These new blockchains do not need to work in the same way as bitcoin. Many of them can adjust its model, for example, by finding alternatives to its energy-intensive “mining” process, which rewards participants with newly minted bitcoins in exchange for providing the computing power needed to maintain the ledger.

A group of authorized participants within an industry can also agree to join a private blockchain. New blockchains also establish and implement business rules, such as transactions that only occur when two or more parties agree, or when another transaction has been completed first. Like Napster and peer-to-peer technology, this innovation is being born/has been born and is being modified. In this process, the blockchain is quickly shedding its negative reputation.

Innovation of Blockchain (New chains on the block)

The spread of blockchains is bad for anyone in the “trust business”—the centralized institutions and bureaucracies, such as banks, clearing houses, and government authorities that are deemed sufficiently trustworthy to handle transactions. Even as some banks and governments explore the use of this new technology, others will surely fight it. But given the decline in trust in governments and banks in recent years, a way to create more scrutiny and transparency could be no bad thing.

The spread of blockchains is bad for anyone in the “trust business”—the centralized institutions and bureaucracies, such as banks, clearing houses, and government authorities that are deemed sufficiently trustworthy to handle transactions. Even as some banks and governments explore the use of this new technology, others will surely fight it. But given the decline in trust in governments and banks in recent years, a way to create more scrutiny and transparency could be no bad thing.

Drawing up regulations for blockchains at this early stage would be a mistake: the history of peer-to-peer technology suggests that it is likely to be several years before the technology’s full potential becomes clear. In the meantime, regulators should stay their hands, or find ways to accommodate new approaches within existing frameworks, rather than risk stifling a fast-evolving idea with overly prescriptive rules.

Drawing up regulations for blockchains at this early stage would be a mistake: the history of peer-to-peer technology suggests that it is likely to be several years before the technology’s full potential becomes clear. In the meantime, regulators should stay their hands, or find ways to accommodate new approaches within existing frameworks, rather than risk stifling a fast-evolving idea with overly prescriptive rules.

The notion of shared public ledgers may not sound revolutionary or sexy. Neither did double-entry bookkeeping or joint-stock companies. Yet, like them, the blockchain is an apparently mundane process that has the potential to transform how people and businesses cooperate. Bitcoin fanatics are enthralled by the libertarian ideal of a pure, digital currency beyond the reach of any central bank. The real innovation is not the digital coins themselves, but the trust machine that mints them—and which promises much more besides.

The notion of shared public ledgers may not sound revolutionary or sexy. Neither did double-entry bookkeeping or joint-stock companies. Yet, like them, the blockchain is an apparently mundane process that has the potential to transform how people and businesses cooperate. Bitcoin fanatics are enthralled by the libertarian ideal of a pure, digital currency beyond the reach of any central bank. The real innovation is not the digital coins themselves, but the trust machine that mints them—and which promises much more besides.

-END-

This article is for learning and reference purposes only, with the hope of helping you, and does not constitute any legal or investment advice. Not your lawyer, DYOR.

We will continue to update Blocking; if you have any questions or suggestions, please contact us!

Was this article helpful?

93 out of 132 found this helpful

Related articles

- LD Capital interprets the past and present of OPNX How is the price performing? What challenges exist?

- What’s happening to the whales on the Bitcoin rich list now?

- Exploring the African Cryptocurrency Market Opportunities and Challenges Coexist

- Explaining RGB Protocol Exploring a New Second Layer for Bitcoin Asset Issuance

- LST will replace ETH as the new underlying asset, and LSDFi may open up a 50x growth market.

- ETH skyrockets A discussion on the future trends of the inscription pathway

- Will Wall Street scare away crypto punks after showing interest in Bitcoin?