Forbes: How did Craig Wright become “Satoshi Nakamoto”?

Forbes: How did Craig Wright become "Satoshi Nakamoto"?Author: Michael del Castillo

Compilation: 0x11, Foresight News

In the fall of 2012, long before most people had heard of Craig Wright, the Australian computer scientist quietly submitted his first bitcoin-related patent, when the value of a single bitcoin was still just $10. The following year, a company called Coinbase raised $5m with the aim of “making bitcoin easier to use for ordinary consumers”. And in 2014, Bitcoin Magazine co-founder Vitalik Buterin published a paper describing a new type of blockchain called ethereum, praising bitcoin’s pseudonymous creator Satoshi Nakamoto for his advances in cryptography.

- Bull market signal? How much longer will Bitcoin stay at $30,000?

- Bitcoin stays stable at $30,000, is this a signal of a bull market?

- Galaxy Digital Founder: Bitcoin ETF Will Become SEC’s “Stamp of Approval”

As the nascent crypto industry focused on bitcoin’s license (which allowed anyone to use the software under copyright law), Wright was seeking to patent the new technology. By December 2015, when Wright was outed as a candidate to be Nakamoto by two news organizations, he had applied for two patents and was the chief scientist at nChain, a Swiss company that had also applied for three patents.

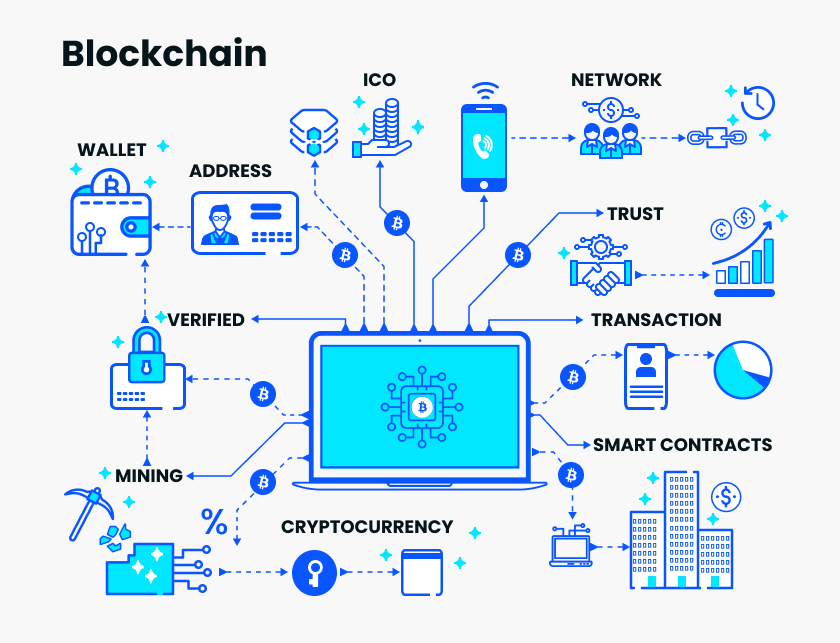

Until recently, a fierce debate raged over whether the 52-year-old Wright was indeed Nakamoto, whose bitcoin wallet contains cryptocurrency worth $3.3bn at current bitcoin prices of around $30,000, and whose blockchain invention allows anyone in the world to send cryptocurrency to anyone else without relying on banks. According to data site Pitchbook, digital currencies have helped entrepreneurs raise $89bn. Next year, Wright is due to go to the UK High Court to prove he is the inventor of bitcoin.

“I created bitcoin,” Wright told Forbes in his London office.

But the focus of that debate could soon shift. Whether or not Wright can prove he invented bitcoin, if he is able to wield the 800 patents he holds across 46 jurisdictions, along with another 3,000 patents pending the way he wants, he is poised to reap a fortune from the trend toward broad blockchain applications. Everything from the $1tn cryptocurrency market to some of the world’s largest companies will be affected. Worryingly, Wright is using legal strategies that could set a precedent for open-source software, including the widely used Meta Javascript framework (React), Microsoft’s Visual Studio for code editing, and Linux, the operating system created by Linus Torvalds, which is linked to 40% of the internet.

“I don’t like Silicon Valley, they’re a cancer on the world,” Wright said. “They can steal anything they want.” He paused for a moment, seeming to reconsider his words, and added: “They’re an anal cancer on the world.”

Craig Steven Wright was born in 1970 in Brisbane, Australia, with a mother who input data on punch cards for early computers and a father who fought in Vietnam. Wright is a polymath, with his personal website listing more than 20 degrees, from master’s degrees in statistics and forensic psychology to a diploma in art appreciation. Over the years, his study of intellectual property (including various uses of blockchain technology) has been subsumed into shell games of trusts and companies.

He says that in 1997 he founded an Australian trust company called Craig Wright R&D. It originally owned Blacknet, which he has described as a precursor to bitcoin. In 2002, he transferred that research to another trust, Ridges Estate.

In the mid-2000s, while studying for graduate degrees in international trade and commercial law, he met American security expert Dave Kleiman on an online forum. Though Wright says he met Kleiman only once, over drinks, before Kleiman died in 2013, the two worked on numerous projects together, including a 2007 book about investigating computer hacking that Wright cowrote and Kleiman edited. A 2015 email provided to Gizmodo purportedly showed Wright asking Kleiman to help edit a paper he was writing about bitcoin. Wright declined to say whether the email was authentic, but he claimed Gizmodo’s article was based on forged documents provided by Kleiman’s estate and steadfastly maintains that he created bitcoin himself. Boies Schiller Flexner, the law firm representing Kleiman’s estate, did not respond to requests for comment.

On Oct. 31, 2008, a group or individual using the pseudonym Satoshi Nakamoto published a white paper describing a “peer-to-peer electronic cash system” — bitcoin — that would allow for online payments to be sent directly from one party to another without “going through a financial institution.” When the bitcoin code was released on Sourceforge software repository in January 2009, Nakamoto added a note allowing anyone to use it under the MIT license terms without restriction. Its copyright was designated as Copyright (c)2009 Satoshi Nakamoto.

Wright said: “The MIT license is very friendly to intellectual property.” He distributed the intellectual property related to Bitcoin to four Australian companies that he controls, each with different businesses. In an email, he wrote that Information Defense obtained intellectual property related to the Bitcoin database; Integyrs received his cryptographic research; Greyfog received IP related to the Internet of Things, and Strassen received research related to the so-called sharding network.

Although the 2010 audit report shows that no patents have yet been “submitted,” Wright said he began working to change this situation in the same year. His first Bitcoin-related patent is a method that multiple users can split access code into a blockchain registry to obtain inheritance and company records, which was granted by the US Patent and Trademark Office in 2017. In December 2010, Nakamoto wrote his last public article, which began with: “There is more work to be done…”.

Wright said that in early 2011, his first wife Lynn and Kleiman founded W&K Info Defense together to develop blockchain-related intellectual property. He also renamed Craig Wright R&D Tulip Trust, which will continue to play an important role in his business strategy. Although the actual composition of Tulip Trust remains a mystery, Wright said that Tulip “owns companies, and only owns companies.”

On December 13, 2010, the creator of Bitcoin logged in using Nakamoto’s pseudonym, which would be one of his last public acts, changing the license from “Copyright (c) 2009-2010 Satoshi Nakamoto” to “Copyright (c) 2009-2010 Bitcoin Developers.” A few days later, Andresen posted a message: “With the blessing of Nakamoto, I will begin more active project management of Bitcoin, although I am reluctant.”

In the spring of the second year, Nakamoto sent what was considered his last private message and then disappeared. “I’ve moved on to other things,” he wrote in an email to former Bitcoin core developer Mike Hearn, “Handing over to Bitcoin core developers Gavin Andresen and others is a good choice.” Hearn said that there was indeed such an email.

A colorful legend emerged: In order for Bitcoin to truly decentralize, it cannot have any flaws, so Nakamoto wrote the code as a gift to the world, and then entrusted a group of open source developers to help it grow into a global currency that does not rely on banks or governments. Nine months later, Gavin Andresen moved the codebase to Github.

On December 8, 2015, after reports of anonymous leaks were published in Wired and Gizmodo, Wright became a controversial public figure in the cryptocurrency world, claiming that he was likely Satoshi Nakamoto, or as Wired put it, “a brilliant hoaxer who very badly wants us to believe.” Wright said, “The Wired and Gizmodo articles are based on information from Ira Kleiman. To fabricate a never-before-existing story about his brother, Ira created documents, made false statements, and used multiple emails to impersonate many people contacting reporters. He did so to obtain money that did not belong to him.”

Matthews, chairman of nChain, said Wright’s newfound fame changed nChain. While his vision for the company has always been to become a long-term software and intellectual property developer, MacGregor sees a Steve Jobs-like figure in Wright who can take the company to the stage before selling it to increase its value. “He wants to sell everything to Silicon Valley,” Wright agrees, “and hasn’t bothered to ask me about Silicon Valley before he does it.”

Wright spoke at several events, including a panel discussion with another “suspect” Satoshi Nakamoto, Nick Szabo, where he and Matthews both claimed that many of the blog posts attributed to the author were actually written by MacGregor. The strategy was to have the world believe once and for all that Wright was Satoshi Nakamoto through a series of “proof meetings.” In April 2016, entrepreneur Jon Matonis and software developer Andresen claimed to have witnessed Wright sign a message related to Satoshi Nakamoto with a crypto signature, and both publicly stated that they believed his claim.

Despite Wright’s apparent use of Nakamoto’s signature, doubts about its authenticity soon surfaced. A Vice report showed that there could be multiple ways to forge the signature. Wright’s subsequent written explanation was rebutted by security researcher Dan Kaminsky, who said the messages could have been sent without knowledge of Nakamoto’s private key (a type of password).

In his apology on his website, Wright seemed to admit that the evidence was not compelling, but he insisted that he was Nakamoto. “As the events of this week unfolded and I prepared to publish the proof that I had access to the earliest keys, I broke. I do not have the courage. I cannot,” he wrote. “From the very beginning, my qualifications and integrity have been under attack. When these allegations were proven false, new allegations began.”

So far, Wright has not provided any further proof publicly, nor has he transferred any bitcoins from Satoshi Nakamoto’s account. One of these methods may be required in an upcoming UK court hearing. Matonis claims that he believes Wright’s articles can still be found on his Medium website, but this year, Andresen added a note to his original statement in May 2016 saying, “It was a mistake to trust Craig Wright like me.”

Matthews said that Wright spent most of his time at home in the following months of 2016, occasionally sending him some invention ideas. The animosity between Wright and MacGregor continued to escalate. “I had to act as a judge in some incredible arguments between the two of them,” Matthews said. “MacGregor told me he didn’t want anything to do with Craig Wright or nChain anymore.” Matthews said he set up a Maltese private equity fund to buy out MacGregor’s stake, and by November 2016, MacGregor had left the company.

Matthews began looking for new funding.

Soon after, he found former billionaire Calvin Ayre, who briefly appeared on a US Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE) wanted list for operating an illegal gambling business in Maryland through Bodog. “We thought we were completely legal,” Ayre said. “Once, it was one of the largest online gaming companies in the world.” In July 2017, he pleaded guilty to a lesser charge and left the company, becoming a private investor again. Matthews, who oversees Ayre’s venture capital work, said he met Wright in 2000 when the inventor helped his gambling industry employer Centrebet with a security audit. Matthews thought the two would hit it off. “He invited Wright in,” Ayre said, “telling me there was someone I had known since 2006. I knew he was Satoshi Nakamoto. So we wanted to talk to you because he needs some help.”

Matthews flew in from his Manila home, Wright flew in from Australia, and the three met on the roof of Ayre’s Vancouver penthouse. The three spent two days drinking wine, getting to know each other, and having a great time. “When I introduced Calvin and Craig, they had an attraction from the moment they looked at each other,” Matthews said. After this meeting, Ayre invested in nChain. “Stefan and I pulled him out,” Ayre said, “built some infrastructure around him, and created a complete ecosystem.”

If nChain is the foundation of the ecosystem, then they start installing bolts and crossbeams. In August 2017, Ayre acquired the cryptocurrency news site CoinGeek. In 2018, Wright, Ayre, and Matthews launched Bitcoin’s fork, Bitcoin Satoshi Vision (BSV), a cryptocurrency based on a version of Bitcoin prior to 2017 that did not include upgrades to make Bitcoin more private. “You can mix, you can transfer, there are no records,” Wright describes transactions in BSV.

According to CoinGecko, BSV has achieved some success, with a market cap of $767 million, ranking 54th on the cryptocurrency market cap list. Wright says he owns a “small amount” of BSV, Ayre says he owns some, “but not a lot,” and Matthews did not respond to questions about his BSV holdings.

In April 2019, Wright registered two copyrights with the US Copyright Office – one for the Bitcoin white paper and the other for the Bitcoin software. The following month, the agency issued a statement saying that “with respect to the two registrations issued to Wright, the Copyright Office does not investigate the truth of any statement made. In the examination process, the Copyright Office noted the well-known pseudonym “Satoshi Nakamoto” and asked the applicant to confirm that Craig Steven Wright is the author and owner of the works being registered. Wright confirmed this.”

If Wright wants to convert the IP into cash, he is likely to do so through nChain. NChain is based in London, where Wright lives, but is officially registered in Zug, Switzerland, a cryptocurrency-friendly country. Nchain’s main source of revenue is royalties and consulting fees for its licenses. Although primarily funded by Ayre, Wright said a private equity fund based in Liechtenstein is also an investor, and his wife is a “trustee.” When asked to clarify whether nChain has a trustee or whether he was actually talking about the Tulip Trust she helps run, Wright said the trust fund is “associated” with nChain.

“I deliberately show no foresight or insight,” Wright laughed when talking about the internal workings of the trust. “Once I know something, someone will want me to take it to court, so I make sure I don’t know. After a long pause, he added: “I deliberately don’t know.” The Kleiman estate’s lawsuit against Wright’s filing shows that there are at least three Tulip Trusts.

Despite having 260 employees, Wright claims this will be nChain’s first profitable year. Chief Intellectual Property Officer Robert Alizon says the company has five individuals licensed, and he expects 20 by the end of the year. He says his main goal is to help entrepreneurs build profitable businesses on the BSV blockchain, but nChain also lays the groundwork for developers creating projects for other blockchain applications to be charged. “We want to support the ecosystem that chooses BSV fundamentally,” says Alizon. “Obviously, if people compete without paying fees, we need to start regulating this. Whether you operate inside or outside BSV, you have the right and must obtain nChain’s permission.” David Pearce is a lawyer living in Birmingham, UK, who tracks 440 nChain patents in Europe alone. He said, “Many of these patents are valid, regardless of whether they are good or bad.” While he represented Bitcoin advisor Arthur van Pelt in challenging three nChain patents, he believes most other patents have been “validly authorized by the European Patent Office, which is generally considered one of the most difficult patent offices in the world.”

But there’s a problem here. Despite having 765 patents in jurisdictions such as the US, Europe, and China, covering themes such as tokenization, identity management, and micropayments, Forbes was only able to find one company paying for a BSV license: Oslo-based supply chain firm Unisot, which paid a one-off license fee. Among other licensed parties, e-Livestock is developing software that allows people in developing countries to use farm animals as collateral, and the company says it has not paid any licensing fees for years. Ed Rivera of blockchain-based movie studio MyMovies says Wright gave him the right to use streaming and encryption patents, although Wright tells Forbes this is not the case. The government of the Philippine province of Batan signed a memorandum of understanding with nChain in December to jointly develop patents owned by the company if a formal agreement is reached.

Smart Ledger, based in New Hampshire, is based on BSV, and its chairman, Bryan Daugherty, says he has no license and does not believe his company needs a license to work, but feels protected by nChain. “They are protecting us,” he said, “hoping to create a good, friendly atmosphere for the emergence of this technology, beyond the cryptocurrency casinos we see today.”

Later in June, the UK High Court said that the COBlocking case, the Bitcoin developer case, and two other cases would be jointly heard from January 2024. In particular, they will study the “identity issue” that the court said applies to each case. “None of these cases will make any progress until Craig Wright proves he is Satoshi Nakamoto,” said patent lawyer Pearce. “They are all related to intellectual property. But they all depend on the premise that Craig Wright is Satoshi Nakamoto. But he’s not.”

Jess Jonas, chief legal officer of the Bitcoin Legal Defense Fund, which represents developers of cryptocurrency-related projects, is less optimistic. “People can’t just bury their heads in the sand and say, ‘Well, you know, he’s not Satoshi Nakamoto, so the court will figure that out and everything will be over,'” she added. “Developers and other industry participants have paid a huge price for having to respond to these claims, and they have to do so because the situation now is about one of the most important open-source licenses. If this protection doesn’t exist, why should people put themselves in danger and develop free open-source software for public use?”

When asked if he was concerned that his patents might have an impact on Bitcoin and other open-source developers, Wright replied, “They are public. If people don’t verify these things, that’s not my fault.” Although Wright said he plans to enforce his intellectual property more broadly, his current focus is on the current case and obtaining licensing fees from those willing to pay. One of the future defendants could be Apple, Wright said, which he claims infringes the copyright by distributing the Bitcoin white paper on some devices.

As Wright prepares for the January High Court hearing, he said much of his legal strategy will depend on the migration of the Bitcoin codebase to Github and alleged attempts to circumvent his administrator control. He described it as a violation of the 1990 UK Computer Misuse Act. “This is a criminal offense,” Wright said.

We will continue to update Blocking; if you have any questions or suggestions, please contact us!

Was this article helpful?

93 out of 132 found this helpful

Related articles

- CoinMarketCap: Overview of the Overall Status of Trading Platforms in the First Half of 2023

- An Explanation of Taproot: Consisting of Three Different Bitcoin Improvement Proposals

- Boring Ape’s decline continues, where should the NFT market break the ice?

- 2017 vs 2023: Fink’s Institutional Bitcoin Perspective

- What is the difference between the supervision and sharing agreement and the information sharing agreement, as institutions compete to include them in ETF filings?

- Will purchasing Bitcoin be a good move for a publicly traded company to enter the world of cryptocurrency?

- 6 Charts Reviewing Cryptocurrency Market Performance in Q2 2023