IMF Working Paper How to Tax Cryptocurrencies?

IMF Working Paper on Cryptocurrency TaxationAuthor | Katherine Baer, et al.

Cryptocurrency and Taxation Design

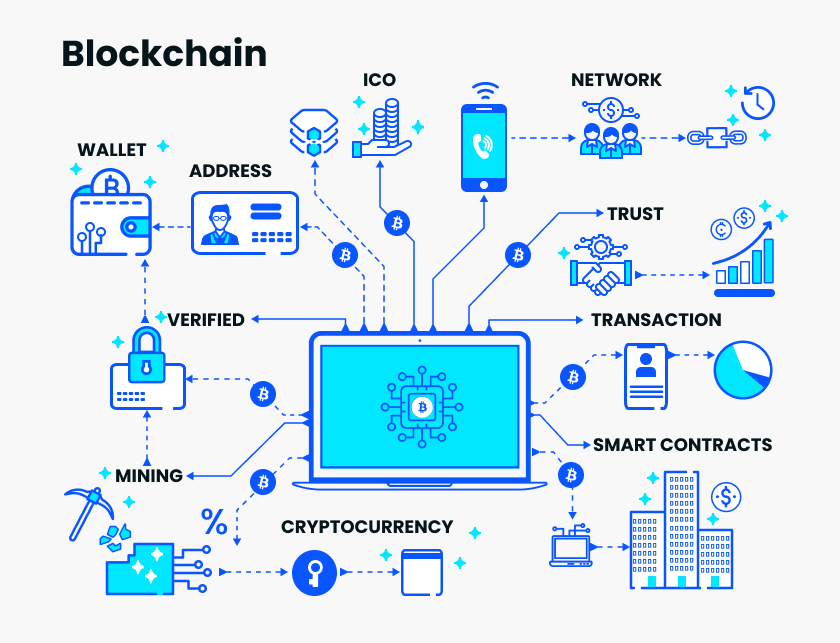

This section explores key policy issues that arise when formulating and evaluating the tax treatment of cryptocurrencies, while deferring related administrative issues for later discussion. Based on the event chain of cryptocurrency transactions and creation (Figure 1), issues related to income tax and value-added tax/sales tax may arise; there may also be purely corrective taxation. Current practices in these areas vary from country to country and often require further clarification, overall being subject to continuous change.

When dealing with these design issues, leaving aside externalities, the currently applicable natural principle is neutrality: taxing cryptocurrencies in the same way as comparable traditional instruments. For example, for miners, there seems to be no reason to treat income from expenses and income from newly created tokens differently from other business income unless there is some specific (non-)incentive. However, due to the dual nature of cryptocurrencies as both investment assets and exchange media, it is difficult to apply the neutrality principle when dealing with cryptocurrencies.

A. Income Tax

Corresponding to these two functions, cryptocurrencies have two main classifications for income tax purposes: as property (like stocks or bonds) or as (foreign) currency. The impact of this distinction depends on domestic regulations but can be significant. For example, many countries exempt individuals’ foreign currency capital gains from tax (Cnossen and Jacobs, 2022). Classifying as property generally results in capital gains tax, but important details such as losses, exemptions, and tax rates varying with holding periods will be crucial. For example, in the United States, classifying cryptocurrencies as property means that capital gains from all transactions are generally required to be reported, with lower tax rates applying if the holding period exceeds one year; if classified as currency, gains should be taxed as ordinary income but only for gains exceeding $200. Similar difficulties exist elsewhere, where treating cryptocurrencies as property requires calculating the gains or losses for each transaction. This obligation could be burdensome for small users and is a major obstacle to using cryptocurrencies for everyday purchases of goods and services.

- LD Capital Cryptocurrency exchanges are frequently deploying Layer2 solutions, carrying ambitious visions for the future market.

- Bankless Cryptocurrencies are entering the final cycle

- Bankless Co-founder The crypto market has entered the last cycle before maturity

There may be a third possibility as well. Some people analogize holding cryptocurrencies to gambling, with the clear implication that taxation should be the same: for example, LianGuainetta (2023). This would not only impact income tax but also value-added tax and sales tax (acquisition being treated as a bet), which have complex treatment for gambling. However, whether this analogy is appropriate is still unclear: in HMRC (2022a), about half of the respondents stated that they hold cryptocurrencies “just for fun,” but Hoopes et al. (2022) found that cryptocurrency sellers report gambling income similar to others.

In practice, the most common approach seems to be to tax cryptocurrencies as property for income tax purposes and comply with the corresponding capital gains tax rules. This still leaves room for various different treatment approaches. Some countries, including European countries, Malaysia, and Singapore, either do not tax capital gains on financial assets or exempt them after a relatively short holding period. Portugal has been trying to position itself as a cryptocurrency-friendly country, explicitly providing for tax exemption on income from holding cryptocurrencies, but currently only for holdings exceeding one year; El Salvador still maintains complete tax exemption.

One notable exception is India. In India, cryptocurrencies are on the regulatory edge: neither illegal nor strictly legal. Nonetheless, the Indian government has implemented a specific tax regime aimed at imposing a 30% tax on the gains and/or income from transactions of “virtual digital assets” (VDA), which includes cryptocurrencies, NFTs, similar tokens, and other assets as designated by the government. An additional tax of 1% is also levied on the transfer of any VDA.

B. Value Added Tax and Sales Tax

The use of cryptocurrencies should not pose significant principled difficulties to the core structure of these tax types, as these taxes are typically formulated in terms of supplies made not in legal tender but in “consideration,” a term broad enough to encompass crypto assets. (However, practical difficulties are likely to arise in applying this term, some of which will be discussed later, such as price volatility (which may impose significant pressure for precise verification of the timing of transactions), the scope for fraud, and the incorporation of cross-border rules, among others.) Some countries, including Australia, Japan, and South Africa, have explicitly exempted the purchase of cryptocurrencies with legal tender from value-added tax. In the European Union, the courts ruled in 2015 that value-added tax should not apply to such transactions.

There also needs to be a clear policy stance on the treatment of fees received by miners and the value added tax on newly issued cryptocurrencies. In principle, there seems to be no reason (unless deliberately creating (dis)incentives) not to impose the full value-added tax on them and grant them corresponding input tax deduction rights. While this is generally seen as a good practice, in practice, many value-added taxes exempt fees for financial services. This would lead to an excessive taxation of the commercial use of cryptocurrencies (as the input tax amount of miners cannot be deducted), while insufficiently taxing personal use.

Figure 1: Schematic representation of events

Note: This chart illustrates the taxable events in the flow of cryptocurrencies (in this case, Bitcoin), highlighting its specific tax policies and management challenges. The sender purchases services from the recipient using Bitcoin through miners, and the recipient can choose to dispose of the Bitcoin or use it to purchase services. “?” represents the need for specific policy/legal clarity. It is not explicitly stated here that these transactions can be peer-to-peer (P2P) or conducted through decentralized or centralized exchanges, which does not affect policy treatment but can impact tax enforcement capability (P2P transactions being the most challenging, followed by decentralized transactions, and lastly centralized transactions).

C. Externalities

The use of cryptocurrencies can generate several types of externalities, which is evident in the calls by many countries for more effective regulation of cryptocurrencies. Some countries, including China, Egypt, Bolivia, and Bangladesh, have even directly banned cryptocurrency transactions or mining. In addition to addressing these externalities through conventional regulatory measures aimed at ensuring financial stability, consumer protection, and combating crime, there may be some externalities that are directly related to the use of cryptocurrencies themselves.

For example, the analogy between gambling mentioned above points to the potential issue of self-control, which can be rationalized through corrective taxation. The widespread substitution of domestic currency with cryptocurrencies (“cryptonization”) may disrupt macroeconomic management tools, significantly reducing the effectiveness of monetary policy or measures on capital flows, which could have implications for the functioning of the international monetary system. For both of these issues, it may be possible to address them through some form of tax on cryptocurrency transactions, similar to the financial transaction taxes levied on traditional financial instruments (including for reducing excessive price volatility), which many people also associate with cryptocurrencies. Another possibility is to use the tax system to prevent transactions as a (suboptimal) stopgap measure before more effective regulation is put in place, in order to address the risks that financial stability faces and reduce the risks faced by less informed investors. India’s 1% transfer tax may indeed be seen as a groundbreaking step towards these goals. However, regardless of the conceptual advantages of a cryptocurrency transaction tax and the unknown benefits it may have in promoting cryptocurrency innovation, implementing such a tax is problematic for reasons similar to those emphasized in Section 5: while nationwide taxation of transactions conducted through centralized domestic exchanges (and/or miners) may be feasible, this may simply push transactions towards peer-to-peer forms or offshore. Nevertheless, similar arguments may also support taking less drastic measures within existing structures, such as rejecting or limiting the offsetting of capital gains tax losses.

However, the most persuasive argument for feasible corrective taxation is the environment. Proof-of-work consensus mechanisms (such as those behind Bitcoin) require a significant amount of energy as they rely on solving complex mathematical problems through a large number of guesses. The associated carbon emissions have raised significant concerns: for example, Hebous and Vernon (forthcoming) estimate that in 2021, the electricity consumption of Bitcoin and Ethereum exceeded that of Bangladesh or Belgium, accounting for 0.28% of global emissions.

Nowadays, awareness of this issue is quite widespread, and the promotion of certain cryptocurrencies as “green” currencies also reflects this. However, voluntary measures alone cannot provide a complete solution. According to the prevailing view, the externalities associated with carbon emissions from mining are best addressed within a general carbon tax, which would automatically internalize the costs of the energy-intensive proof-of-work validation mechanism. However, in the absence of a carbon tax, there are reasons to consider more targeted tax measures. In March of this year, the Biden administration proposed a 30% tax on the electricity consumption of miners, but without (at least for now) distinguishing based on the carbon intensity of the electricity generation. Kazakhstan (an important mining location) also plans to introduce a similar tax starting in 2023, but with a reduced tax rate for miners using renewable energy. Without such additional taxation, a less efficient but still meaningful measure could be to restrict or deny income tax exemptions on energy costs incurred in mining activities, as well as/or (if not exempt from value-added tax) not allowing deduction of input tax on energy costs.

We will continue to update Blocking; if you have any questions or suggestions, please contact us!

Was this article helpful?

93 out of 132 found this helpful

Related articles

- If room temperature superconducting materials can be realized, will it have a negative impact on the cryptocurrency market?

- Why the crypto community should pay attention to room-temperature superconductivity

- Changtui 7 major predictive indicators suggest that the market may be fully bullish.

- Wu said Zhou’s selection Hong Kong regulatory agency opens retail trading, Curve hacked, Binance US Department of Justice progress and news Top10 (0729-0805)

- Which is more important, encrypted narrative or product construction?

- LianGuai Observation | Understanding the July Cryptocurrency Market in 7 Pictures DeFi Unaffected by Curve Vulnerability

- Infinite ‘Bullets’? Discussing the Hidden Concerns of the Largest BTC Listed Company MSTR